Safeguarding adults

Safeguarding adults

Headlines

- Abuse and neglect of anyone is intolerable, especially of vulnerable adults.

- Safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility. People that have direct or indirect contact with vulnerable adults, or who have access to information about them, have a responsibility to safeguard and protect their welfare.

-

If you would like to see more information about children please visit: Vulnerable Children

Why is this issue important?

The high cost of abuse and neglect, both to individuals and to society, underpins the duty on all agencies to be proactive in safeguarding adults.

The experience of abuse and neglect is likely to have a significant impact on an adult’s health and wellbeing. By its very nature, abuse, as the misuse of power by one person over another, has a large impact on a person’s independence and their ability to exercise choice and control over the fundamental aspects of their life. This causes humiliation and loss of dignity.

It is not only the stressful events of maltreatment that have an impact, but also the context in which they take place. Often, it is the interaction between a number of factors that increases the likelihood and level of harm.

There is a duty on organisations to safeguard and promote the welfare of vulnerable adults. It is a shared responsibility and effectiveness depends upon commissioning activity, and efficient joint working between agencies to respond to incidents of abuse and neglect. In addition, there is an increasing focus on preventing abuse occurring in the first place.

Community Assets and Action

What would an asset-based approach to safeguarding adults look like?

The wider community can help safeguard the people who live alongside them. One of the ways this can be done is to raise awareness of safeguarding issues and how everyone in the community can contribute to looking out for their family, friends and neighbours, or even a stranger. Whilst some people and organisations have statutory duties around safeguarding, the general population also has a moral duty to ensure those around them are safe and free from abuse.

There are actions businesses and regulated sectors such as banking, gambling and public transport amongst others can do to ensure the people they serve are effectively safeguarded. This could be through effective service design and automated safeguarding alerts and risk awareness triggers.

Businesses and organisations also have a duty to ensure the technology they use reduces the opportunity for abuse, and also does not perpetuate abuse by allowing for example the sharing of misappropriated data or images of abuse.

What are the community assets and action around this?

The biggest asset around safeguarding is awareness and understanding. Safeguarding is one of those issues where an increase in numbers could be a good news story because people know how they report their concerns.

There are also a wide range of assets that support victims and survivors of many forms of abuse, some of which may have occurred in childhood. These include organisation such as: Age UK, Pennine Domestic Abuse, Women’s Centre, Brunswick Centre, Kirklees Rape and sexual abuse counselling service, Rape crisis, Safe Line, Samaritans, SWYPFT – Adult psychological therapies service (APTS), Victim Support, Ben’s Place – Male Support, Male Survivors UK, National Association for People Abused in Childhood, Support Line, Survivors West Yorkshire.

Healthwatch Kirklees

Healthwatch Kirklees is the independent consumer champion for the public in Kirklees on matters relating to health and social care. It has a seat on the Health and Wellbeing Board and contributes to feedback as part of commissioning and decision making for local health and social care services. It is important to us to improve our understanding of community awareness of adult abuse. The local relationship with Healthwatch continues to develop in a dynamic way and they have worked to evaluate how much learning had taken place in Kirklees following a Safeguarding Adults Review.

What significant factors are affecting this issue?

Mental capacity

We all make decisions, big and small, every day of our lives and most of us are able to make these decisions for ourselves, although we may seek information, advice or support for the more serious or complex ones. For significant numbers of people their capacity to make certain decisions about their life is affected either on a temporary or on a permanent basis.

Someone lacking capacity because of an illness or disability such as a mental health problem, dementia or a learning disability may not be able to:

- Understand information given to them about a particular decision

- Retain that information long enough to be able to make the decision

- Weigh up the information available to make the decision

- Communicate their decision.

Lacking capacity in this way and being dependent on others for decision-making advice and support can leave individuals at greater risk of experiencing abuse.

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons”. FGM is widely practised in some countries, including countries where it is illegal. In England and Wales the Female Genital Mutilation Act of 2003 made it illegal to perform (or aid, abet or procure) FGM on a British Citizen in the UK or overseas, even where FGM is legal in that country. (1)

The reasons and motives for FGM are complex and often associated with culture, traditions and beliefs such as preserving chastity, rites of passage, family honour and “cleansing” / “purifying” the girl, making them more suitable for marriage. Within no religious teaching is FGM advocated or supported. There are also no health benefits to FGM; it is an extremely harmful practice.

The World Health Organisation estimates that between 100 and 140 million girls and women worldwide have experienced FGM. Research in 2015 relating to England and Wales suggests that around 60,000 girls aged 0-14years were born to mothers who had undergone FGM and 103,000 aged 15-49 years who have migrated to England and Wales are living with the consequences of FGM. Approximately 10,000 girls aged under 15 years who have migrated to England and Wales are likely to have undergone FGM (2). It is highly likely that these cases will be concentrated in areas where there is a higher concentration of practising communities from Africa and parts of the Middle East and Asia. In Kirklees, intelligence relating to FGM is very limited.

Self-neglect

In the Care Act (2014) self-neglect is included as a category under adult safeguarding. Self-neglect is an extreme lack of self-care that can include:

- Lack of self-care to an extent that it threatens personal health and safety

- Neglecting to care for one’s personal hygiene, health or surroundings

- Inability to avoid harm as a result of self-neglect

- Failure to seek help or access services to meet health and social care needs

- Inability or unwillingness to manage one’s personal affairs

In some cases, where the adult has care and support needs, safeguarding responses may be appropriate. However, the inclusion of self-neglect in statutory guidance does not mean that everyone who self-neglects needs to be safeguarded. Safeguarding duties will apply where the adult has care and support needs (many people who self-neglect do not), and they are at risk of self-neglect and they are unable to protect themselves because of their care and support needs. In most cases, the intervention should seek to minimise the risk while respecting the individual’s choices. (3)

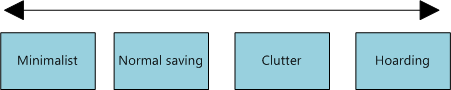

Self-neglect: Hoarding

Hoarding is sometimes associated with self-neglect and can present similar safeguarding concerns. Hoarding behaviour is best thought of in terms of a spectrum: saving and collecting possessions can range from being totally normal to excessive or pathological. Most children have collections of something at some point, and approximately 30% of British adults define themselves as collectors. Hoarding is not the same as collecting; collectors look for specific items, such as model cars or stamps, and may organize or display them. People with hoarding disorder often save random items and store them haphazardly.

Hoarding means excessively acquiring items that appear of little or no value and not being able to throw them away, resulting in unmanageable amounts of clutter. Often, many of the things kept are of little or no monetary value, and may be what most people would consider rubbish. Hoarding is challenging to treat because many people who hoard don’t see it as a problem, or have little awareness of their disorder and how it’s impact on their life or the lives of others.

It is estimated that around 2-5% of the UK adult population experiences symptoms of compulsive hoarding. (3) In Kirklees this would mean there are between 20 and 50 people per 1000 adult population (6,600 – 16,500 people in the Kirklees population) that are compulsive hoarders. Only a small number of which may become known to services.

Hoarding represents a great burden for the sufferers, their families and society. Hoarding is also often associated with forms of anxiety and depression. (4) Although some people may experience a gradual rise in symptoms throughout their lifetime, others may develop hoarding symptoms quite quickly after a stressful life event. (5)

Some research finds that hoarding disorder is more common in males but more females present for support. It is a stereotype to associate hoarding tendencies with older people. (6) Hoarding can happen in any age group, gender, ethnic group, socio-economic group, educational attainment level, occupation or tenure.

There is a new diagnosis in DSM-V (7) of Hoarding Disorder because research has shown that it is a distinct disorder with distinct treatments rather than being grouped under obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. This diagnosis would apply to hoarding that occurs in the absence of, or independently from, other health or mental disorders.

A note on hoarding and self-neglect: Hoarding and self-neglect can present together or be related; however, care needs to be taken not to label every case of hoarding or excessive collecting as self-neglect. Some people neglect (seem not to care about) cleanliness of themselves, their dependants or their homes and don’t get rid of rubbish but this may be due to a broad range of possible other health conditions such as dementia, schizophrenia, drug addiction or alcoholism, to name a few. Others are physically or cognitively unable to take action to manage their living environment.

Financial Abuse

Financial Abuse/harm is another name for stealing or defrauding someone of goods and/or property, including money. It is always a crime but is not always prosecuted. Sometimes the issue is straightforward, for example a care worker stealing from an older person’s purse, but at other times it is more difficult to address. This is because very often the perpetrator can be someone’s son, daughter or other family member, or age prejudice means that other people assume it is not happening or that the older person is to blame.

Financial abuse/harm can happen because the older person can be seen as an easy way of getting money, particularly if they are dependent or confused. It can happen because there is an assumption that the likelihood of criminal penalties is small if the perpetrator is caught. And it can happen because the current protective systems are weak.

What does local data tell us?

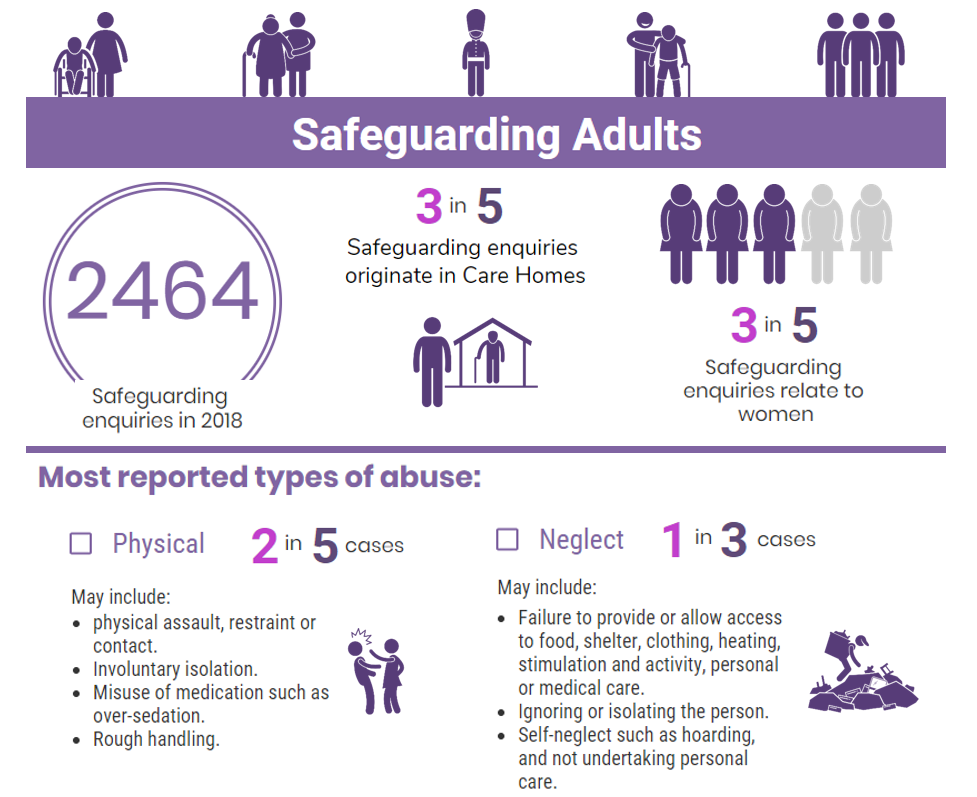

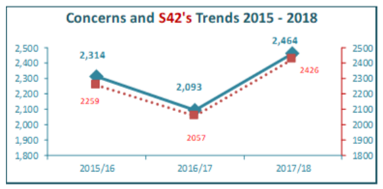

Safeguarding concerns trends in Kirklees, 2015 – 2018

Previously the data only showed the enquiries that involved a formal multiagency plan. However now we have captured all cases where concerns met the Care Act criteria. This does not mean that that cases of abuse have risen significantly locally.

- A concern is a sign of suspected abuse or neglect that is reported to the council or identified by the council. An enquiry is where a concern has met the Care Act criteria, called Section 42 enquiries.

- An enquiry is the action taken or instigated by the local authority in response to a concern that abuse or neglect may be taking place. An enquiry could range from a conversation with the adult, right through to a much more formal multi-agency plan or course of action. In the majority of cases the enquiries have been dealt with through minimum intervention.

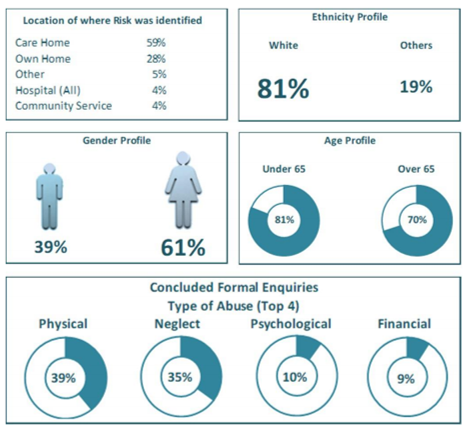

Profile of Safeguarding Enquiry Cohort 2017/18 – Kirklees Level Data (8)

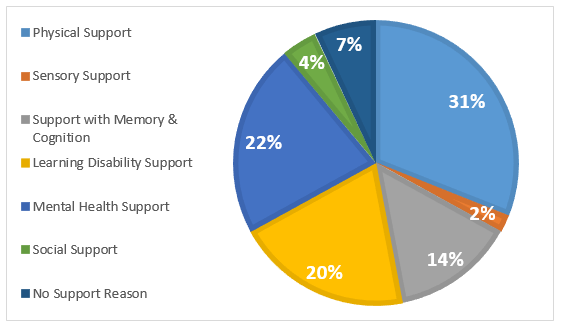

Safeguarding Enquiries by Primary support reason 2017/18 – national data (9)

Which groups are affected most by this issue?

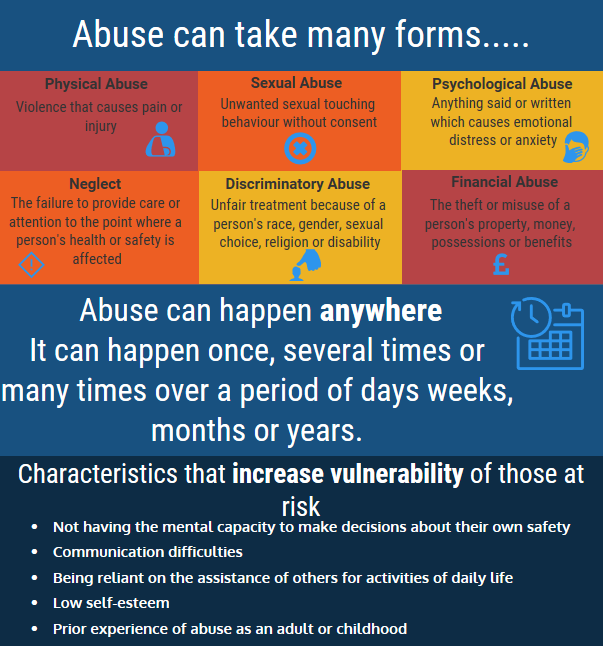

Anyone can be affected by abuse. However adults more at risk include those that:

- Has needs for care and support.

- Is experiencing or is at risk of abuse or neglect, and as a result of their need for care and support is unable to protect himself or herself against the abuse or neglect or the risk of it.

- Is an older person who is frail due to ill health, physical disability or cognitive impairment.

- Has a learning disability.

- Has a physical disability and/or sensory impairment.

- Has mental health needs including dementia or a personality disorder.

- Has a long-term illness/condition.

- Misuses substances or alcohol.

- Is an unpaid carer such as a family member/friend who provides personal assistance and care to adults and is subject to abuse.

- Lack the mental capacity to make particular decisions and is in need of care and support.

Where is this causing greatest concern?

Vulnerable people may be at risk anywhere. While sharing common themes of risk, each group or community may also have specific issues. The diversity of Kirklees people means that professionals must have the skills and resources to be able to identify and provide an appropriate response to all cases where vulnerable children and adults are, or potentially could be, at risk from harm.

What could commissioners and service planners consider?

- Provide strategic and effective collaboration including working productively across Kirklees to safeguard all vulnerable people.

- There is the need for a strong prevention theme in all safeguarding work: encouraging and supporting those working with vulnerable people to recognise common precursors or risk factors of abuse and develop strategies with individuals to mitigate them would be a positive step.

- Continue accessible training to give people, especially those staff and volunteers working in settings that mean they are more likely to come into contact with children or vulnerable adults who are at risk of abuse, the skills to identify concerns and how to ensure that appropriate action is taken is crucial, especially in cases of neglect.

- Ensure the support provided by children’s, adult and family services is co-ordinated and takes account of how individual problems can affect the whole family.

- Safeguarding must remain central to our joint health and social care commissioning strategies and other plans for children and young people’s services.

- FGM – Preventative work should seek to ensure that FGM does not occur. Families must be made aware that it is illegal to carry out FGM in the UK, as is removing a child from the UK for the purposes of FGM. They should be made aware of the health and legal implications. It is vital that there is effective communication and engagement to influence these perceived cultural norms.

References

1) Kirklees FGM Prevention Strategy, available at: https://www.kirkleessafeguardingchildren.co.uk/managed/File/Info%20for%20Professionals/Kirklees%20FGM%20Strategy%20FINAL%20July%202016.pd

2) Macfarlene A & Dorkenoo E (2015) Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation in England and Wales: National and local estimates. London: City University London and Equality Now http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/12382/

3) Social Care Institute for Excellence, “Self-neglect at a glance” (October 2018). Available at: https://www.scie.org.uk/self-neglect/at-a-glance

4) NHS, “Hoarding”, http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/hoarding/Pages/Introduction.aspx

4) Singh S, Jones C. Visual Research Methods: A Novel Approach To Understanding The Experiences of Compulsive Hoarders: A Preliminary Study. JCBPR. (2012), [cited April 24, 2015]; 1(1): 36-42.

5) Grisham, Jessica R., and Melissa M. Norberg. “Compulsive Hoarding: Current Controversies and New Directions.”Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2 (2010): 233–240. Print.

6) Pertusa, A., Fullana, M. A., Singh, S., Alonso, P., Menchon, J. M., & Mataix-Cols, D. (2008). Compulsive hoarding: OCD symptom, distinct clinical syndrome, or both. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(10), 1289−1298.

7) http://www.dsm5.org/Documents/Obsessive%20Compulsive%20Disorders%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf

8) Safeguarding Board Annual Report 2017/18. Available at: http://www.kirklees.gov.uk/beta/adult-social-care-providers/pdf/kirklees-safeguarding-adults-board-annual-report.pdf

9) Adult Social Care Statistics Team, NHS Digital, Safeguarding Adults England: 2017/18. Available at:https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/safeguarding-adults/annual-report-2017-18-england

If you are concerned that an adult at risk living in Kirklees is being abused you should see Report abuse or neglect of an adult at risk

Date this section was last reviewed

June 2019, CP