![]()

Tobacco, alcohol, drug misuse

Tobacco, alcohol, drug misuse

Tobacco, alcohol and drugs misuse introduction

Tobacco, alcohol and drugs misuse are presented here as separate sections, but is important to recognise the links between them as risky health behaviours often present together and influence each other, and may require integrated services to enable people to access support for multiple related issues in a holistic way. Additionally, the risk factors associated with these behaviours can often be the same or interdependent (e.g. vulnerable young people, behaviours of parents and peers, unemployment, deprivation, etc.).

For example, the Current Living in Kirklees Survey (2016) showed that:

- Smokers are significantly more likely than non-smokers to also exceed recommended safe drinking levels and use drugs

- g. 1 in 20 non-smokers had used illegal or recreational drugs compared to more than 1 in 5 smokers

- People who have used recreational or illegal drugs are significantly more likely than those who haven’t to also be smokers and exceed recommended safe drinking levels

- g. More than 1 in 3 of people who have used drugs in the last 5 years and 6 in 10 of people who are regular drug users are also smokers, compared to just 1 in 10 of those who have not used drugs

- People who exceed the recommended safe drinking levels are significantly more likely than those who don’t to also smoke and use drugs

- g. Approximately 1 in 6 of those who exceed the recommended safe drinking levels smoke compared to 1 in 10 of those who don’t exceed the recommended safe drinking levels

Addiction and mental health

People with an addiction may have dependencies on both drugs and alcohol, or may be regular tobacco smokers as well as experiencing problems with alcohol and drugs misuse. These behaviours may also be accompanied by or contribute to a mental health need, or vice versa (e.g. smoking is often cited as a coping strategy for mental health issues; drug misuse as self-medication amongst people who feel anxious or depressed can exacerbate or lead to further mental health problems). It is therefore important to recognise the interdependencies between all of these health needs rather than treating them in isolation.

Tobacco, alcohol and drugs misuse introduction: References

Kirklees Council (2016), Current Living in Kirklees (CLiK) Survey 2016

Tobacco, alcohol and drugs misuse introduction: Date this section was last reviewed

July 2019, RC

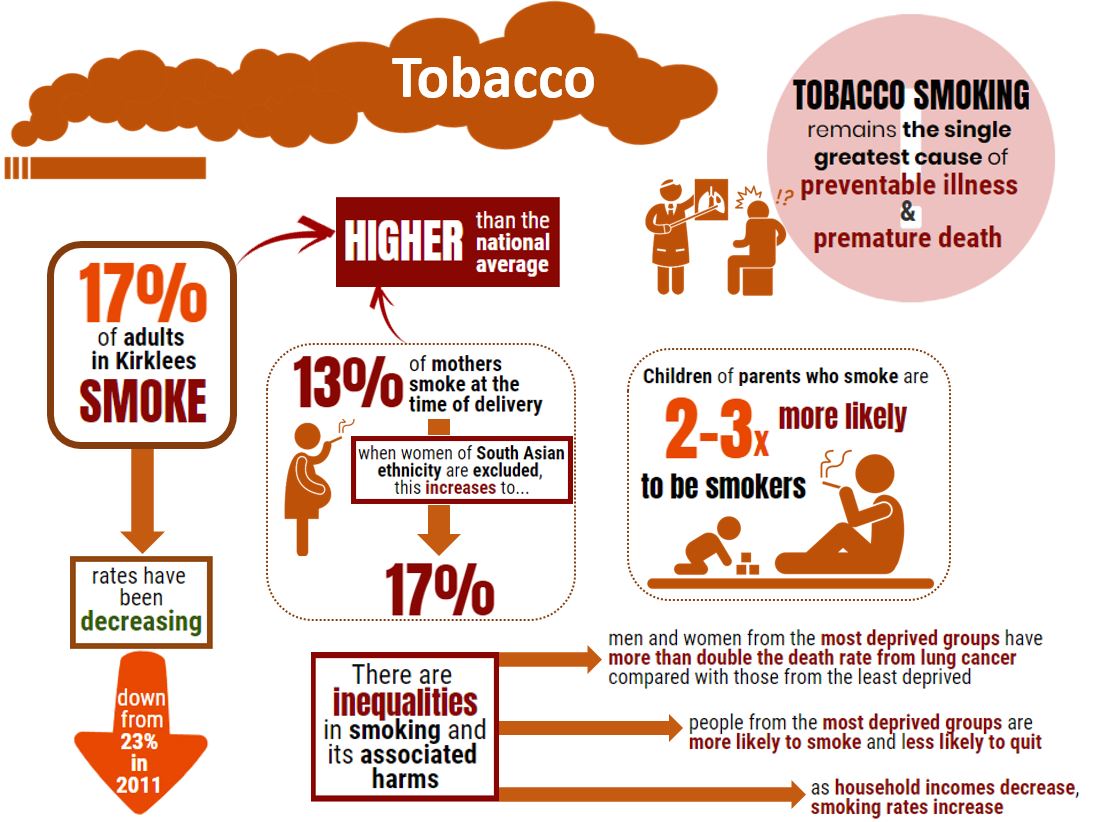

Tobacco: Headlines

Tobacco: Why is this issue important?

Despite tobacco smoking being on a downward trajectory, smoking remains the single greatest cause of preventable illness and early death in England (1). In 2016, 1 in 6 (16%) of all deaths in adults were estimated to be caused by smoking (2). Smoking is associated with a wide range of health problems, including cancer, coronary heart disease and respiratory disease.

Smoking in pregnancy increases the risk of stillbirth and babies born to mothers who smoke are more likely to be born underdeveloped and in poor health (3).

There is no safe level of exposure to tobacco smoke and there are long-term health effects. Second-hand (passive) smoking continues to be a major risk to health of non-smokers, especially for children who are at greater risk to developing lower respiratory tract infections, middle ear infections, wheeze asthma, bacterial meningitis and cot death (4).

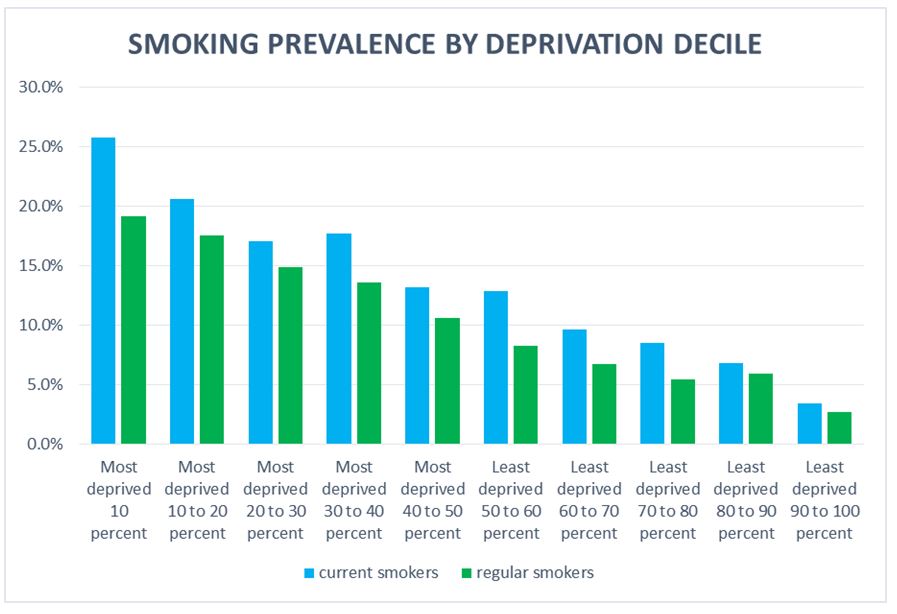

Smoking and the harm it causes aren’t evenly distributed. People in more deprived areas are more likely to smoke and are less likely to quit. Men and women from the most deprived groups have more than double the death rate from lung cancer compared with those from the least deprived. Smoking is twice as common in people with longstanding mental health problems (5).

Tobacco: What significant factors are affecting this issue?

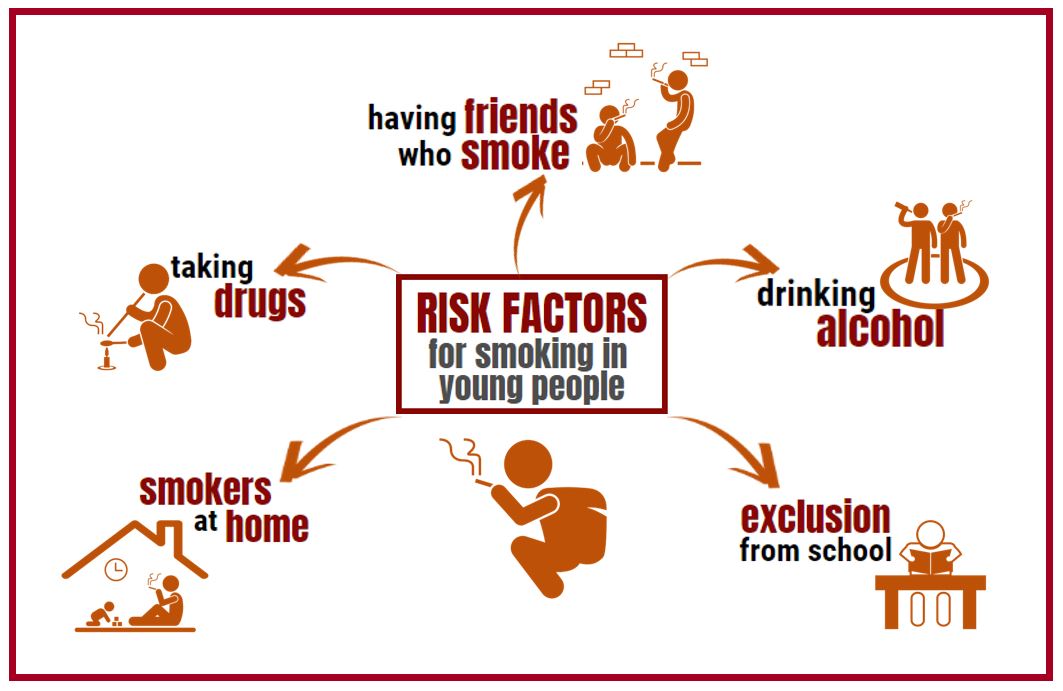

Children and Young People

There is a strong association with children taking up smoking when living with peers or family who smoke. Children who have a parent who smokes are 2 to 3 times more likely to be smokers themselves (3).

Children are more likely to become smokers if they also use alcohol or drugs, are disengaged from education or have poor educational outcomes, or have mental or emotional problems. Young people are also influenced by price and availability, restrictions on smoking in public places and advertising and product placement. Each year, in England alone, around 330,000 children under 16 first try smoking and most smokers start smoking regularly before they are 18 years old (6).

E-cigarettes

E-cigarettes (EC) are increasingly being used by smokers to help quit smoking. They have become the most popular quitting aid and have helped with reducing cigarette consumption (7). Evidence shows that e-cigarettes are estimated to be 95% less harmful than smoking and could be contributing towards at least 20,000 smoking quits per year (8).

Data from several representative surveys suggest that e-cigarette use among all adults in Great Britain has remained stable since 2015. In 2017 to 2018, estimates for prevalence were (9):

- 4% to 6.2% for all adults

- 9% to 18.5% for current smokers

- 4% to 0.8% for people who had never smoked

- 3% to 11.3% for ex-smokers (vaping prevalence declined as the time since they had stopped smoking increased)

Nationally, compared to adults, use of EC among young people is low. Use or experimentation with e-cigarettes increases with age; 3% of 11 year olds said they’ve tried an e-cigarette once or twice and this rises to 23% of 18 year olds. At least weekly use is 0% for 11 year olds increasing to 3% of 18 year old (10).

There is no evidence, either nationally or locally at present, that suggests EC are renormalising smoking or increasing smoking uptake, and smoking rates are continuing to decline for both young people and adults (11).

Locally, in 2016 (12), 14% of all adults had tried e-cigarettes, and 6% were current e-cig users, with 3% using an e-cig every day. The most common reasons given for using e-cigs were: “it is healthier than smoking tobacco” (44%); “it is cheaper than tobacco” (34%); “I am trying to stop smoking tobacco altogether (32%); and “I am cutting down on the amount of tobacco I smoke” (30%).

Illicit tobacco

Although the illegal tobacco market is in long-term decline, it continues to be a problem in some local communities (Cancer Research UK, 2018). Illegal tobacco, sometimes referred to as ‘illicit’ tobacco, is the unlawful supply of tobacco products (such as cigarettes and hand rolling tobacco) which have not had the duty (tax) paid on them or they have been smuggled into the country or illegally produced (13).

The illegal tobacco trade not only fosters criminality, it contributes to health inequalities and poor health outcomes for populations already disadvantaged.

The harm of illegal tobacco

Unregulated sales and availability of illegal tobacco is cheaply available and therefore more accessible, making it easier to for children and young people to take up the habit. It also encourages established smokers to smoke more than if they were paying full price and makes it less likely they will quit. Poorer smokers are also more likely to purchase illegal tobacco (14). Unlike licensed tobacco products in the UK, counterfeit cigarettes contain higher levels of cancer-causing toxins, and also pose an additional fire risk as they fail to extinguish themselves when left to burn (15). https://www.wired-gov.net/wg/news.nsf/articles/LGA+Illegal+tobacco+trade+harming+efforts+to+cut+smoking+councils+warn+17052016134000?open

Quitting

Over 58% of smokers still try to quit without using an aid and going ‘cold turkey’ despite this being the least effective way , and there are still many misunderstandings about the harmfulness of nicotine containing products, such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and e-cigarettes (16). The use of quit aids can greatly increase someone’s chances of quitting successfully. Research shows that (16):

- Using NRT as a quit aid, such as patches and gums, or e-cigarettes makes it one and a half times as likely you’ll succeed.

- Combining quit aids (prescribed by a GP, pharmacist or other health professionals) and accessing specialist support makes it four times as likely you’ll stop smoking successfully.

Tobacco: Community assets and action

What would an asset-based approach to tobacco look like?

An asset-based approach to tobacco should focus approaches to reducing the prevalence of tobacco smoking on promoting the right messages and creating supportive services and environments to aid people to quit.

What are the community assets and action around tobacco?

Supporting people to quit smoking goes beyond the remit of healthcare services. It requires a systems wide approach to reduce smoking rates, reducing smoking related harms and preventing take up of smoking in the first place. This approach is being developed in Kirklees in the following ways:

- Services and therapies – In Kirklees, a number of GP practices, pharmacies and community based organisations offer stop smoking services that include one to one support and nicotine replacement therapy. Stop smoking support is widely available to population groups where we have the highest prevalence of tobacco use.

- Supportive environments – Regional and local partnership working has enabled key organisations and stakeholders to strengthen smoke free policies and support measures across a number of settings where target populations come into contact, such as health and social care, sporting venues, parks and open spaces and workplaces.

- Restricting illegal tobacco – Dedicated resources and capacity is provided by key enforcement agencies to collate data intelligence and act on this to control the supply and availability of illegal tobacco.

Stop smoking provision in Kirklees

Through a distributed stop smoking service via participating GP’s, pharmacies and community organisations, this model of delivery is starting to show successful outcomes.

“As a non-medical prescriber I had undertaken the smoking cessation training. Through our stop smoking commissioned service at a local high school, I worked with a year 10 girl in her school over several weeks preparing her for her ‘quit’ attempt. After exploring the various quitting aids the girl decided that she would like to try microtabs which can be used sublingually to curb cravings. I issued a voucher for the microtabs which the girl was able to take to her local pharmacy where the quitting aid was dispensed. I had follow up appointments with the girl and to date, she has successfully managed to abstain from smoking. She said that having the service in school made it so much more accessible and she doubts that she would have been able to stop smoking otherwise”.

Source: Locala, 2018 (17)

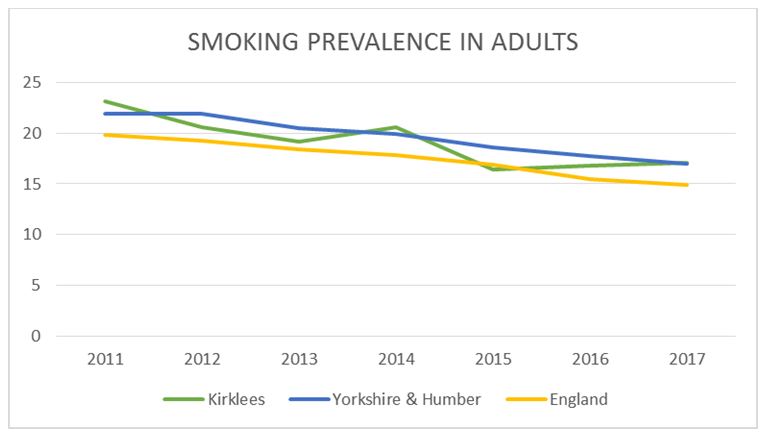

Tobacco: What does local data tell us?

National statistics show that 17% of the adult population in Kirklees smoke, compared to 15% nationally. This is down from 23% in 2011, reflecting national and regional trends of declining rates of smoking (18).

In the 2015-17, 287 per 100,000 deaths in the Kirklees population aged 35+ were attributable to smoking, which is worse than the national rate of 263 per 100,000, but less than the regional rate of 300 per 100,000 (19). In Kirklees in 2017/18, 1754 per 100,000 hospital admissions for those aged 35+ were attributable to smoking, which is worse than the national rate of 1530 per 100,000, but less than the regional rate of 1823 per 100,000 (18). However, both mortality and hospital admissions attributable to smoking have decreased in recent years (19).

Local statistics that show that of current smokers in Kirklees, 78% planned on quitting, with 23% intending to do so within the next 6 months (12).

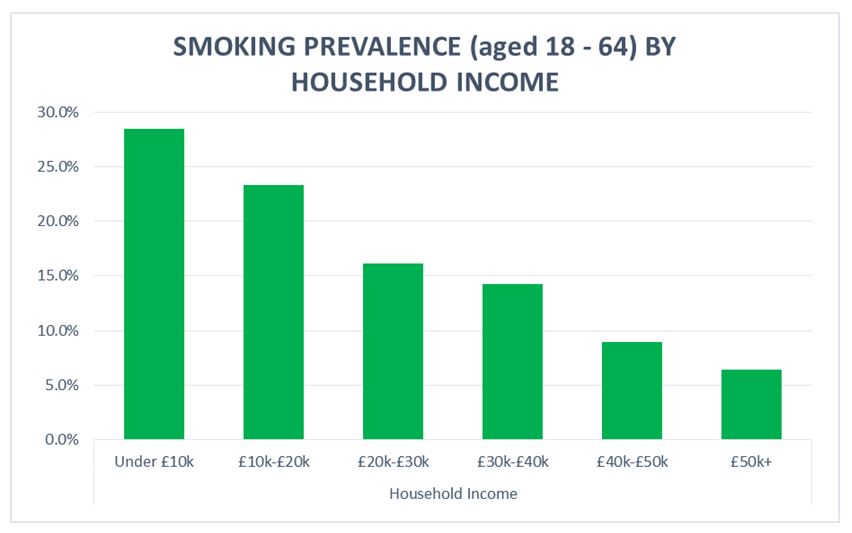

Similarly, smoking is also linked to income. 1 in 3 (29%) 18-64 year- olds in Kirklees with household incomes under £10,000 smoke compared to less than 1 in 4 (24%) with incomes of £10,001-£20,000, and as household income increases, smoking prevalence continues to decrease, as shown in the graph below (12). This reflects a similar national trend.

Children and young people

The majority of smokers start smoking while they are young: 66% before the age of 18 and 83% before the age of 20 (20).

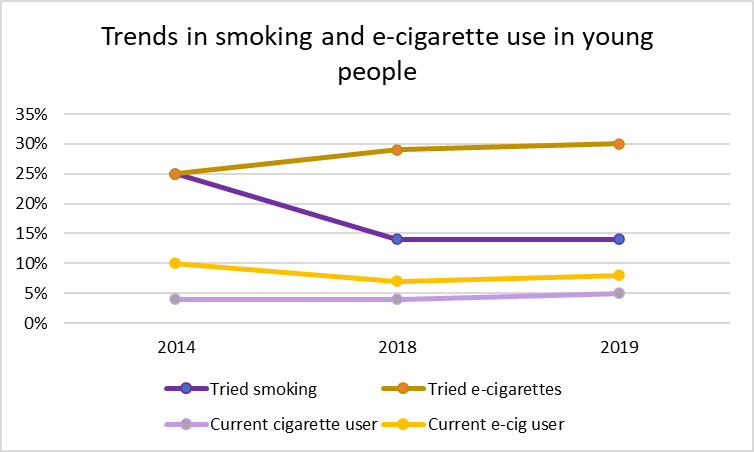

Locally, the number of 14-year olds who have tried smoking has declined significantly over the past 10 years, from 47% in 2005 to 14% in 2019. The number of 14-year olds who say they currently smoke cigarettes at least once a week has also been declining, from 15% in 2005 to 1% in 2019 (21).

In the 2019 Young People’s Survey (21), a similar proportion of boys and girls said they have tried smoking cigarettes (13% vs 14%). Slightly more girls than boys said they currently smoke (5% vs 4%).

Young people of White Other ethnicity were more likely to have tried smoking, which has increased since 2018 (32% in 2019 vs 26% in 2018). In contrast, young people of Asian ethnicity were less likely to have tried smoking (7%).

17% of White Other ethnicity pupils were current smokers compared to 6% of mixed ethnicity pupils. The prevalence of current smokers in young people of Black ethnicity has decreased from 15% in 2018 to 8% in 2019. LGBT+ young people were almost twice as likely than average to have tried smoking (27%) and were over twice as likely to be current smokers (13%).

E-cigarette use

The proportion of young people who had tried e-cigarettes increased from 25% in 2014 to 30% in 2019, with a similar proportion of current e-cigarette users in 2019 (8%) compared to 2018 (7%). Unlike cigarette smoking where rates were similar, a greater proportion of boys had tried e-cigarettes compared to girls (33% vs 29%). However, only slightly more boys were current e-cigarette users compared to girls (9% vs 8%).

Young people of White Other ethnicity and Black ethnicity were more likely to have tried e-cigs (51% and 50%). Just under a quarter of young people of White Other ethnicity said they were current e-cigarette users (23%).

Twice as many LGBT+ young people said they were current e-cigarette users compared to other young people of Kirklees (17%).

A similar proportion (3%) of young people said that they had either smoked tobacco first and moved on to e-cigarettes, or had tried e-cigarettes first before moving on to tobacco cigarettes (21).

Tobacco: Which groups are most affected?

Smoking is complex and related to a number of factors such as: unemployment, income level and socio-economic class, ethnicity, low educational attainment and mental health problems. Despite smoking rates declining, there are a number of vulnerable population groups where rates remain high (19).

Adults

Nationally, 17% of men smoke compared with 13.3% of women, and those aged 25-34 continue to have the highest prevalence of smokers at 1 in 5 (19.7%) (18). The latest Current Living in Kirklees Survey (CLiK) (12) shows that there was little difference in smoking habits between men (17% are current smokers) and women (15% are current smokers). The highest prevalence was in those aged 18-24 (25%), and smoking decreased with age: 19% in those aged 25-34; 16% in those aged 53-44, 45-54 and 55-64; 11% in those aged 65-74; 5% in those aged 75+.

Routine and Manual Workers

In the UK, around 1 in 4 (25.9%) people in routine and manual occupations smoked, compared with just 1 in 10 people (10.2%) in managerial and professional occupations (Office of National Statistics 2017). In Kirklees, 29% of those in routine and manual occupations are current smokers (18).

Pregnant women

Prevalence of smoking during pregnancy is a significant health inequality with distinct variations across communities and social groups. In 2017/18, 13% of all pregnant women in Kirklees smoked at time of delivery, with levels being highest in Birstall and Birkenshaw (16%), Spen (15%), and Huddersfield South (14%) compared to the England average of 11%. However, when women of a South Asian ethnicity are excluded from these figures (due to acknowledged lower levels of smoking prevalence) the rates of smoking at time of delivery are much higher. The Kirklees overall rate for smoking in pregnancy increases to 17%, and at a locality level Batley (23%), Dewsbury (23%) and Spen (19%) have the highest rates (22).

Those with long-term conditions, including mental health

The 2016 CLiK survey (12) shows that smoking was more prevalent in people with long-term conditions than those without (16% compared to 12%), and many people suffering from smoking-related conditions continued to smoke. For example, almost 1 in 3 people with COPD (29%), 1 in 5 people with asthma (19%), and 1 in 5 (19%) people who have had a stroke were current smokers.

People experiencing mental health problems are more dependent on nicotine and smoke significantly more than the population as a whole (23). In Kirklees, the latest GP Patients Survey (24) shows that 1 in 3 adults with a long-term mental health condition are current smokers. Smokers with mental health conditions are more likely to have smoking related diseases such as cardiovascular disease, lung disease and cancer. Smoking is associated with poor outcomes, such as greater depressive symptoms, greater likelihood of psychiatric hospitalisation and increased suicidal behaviour (25).

Tobacco: Where is this causing greatest concern?

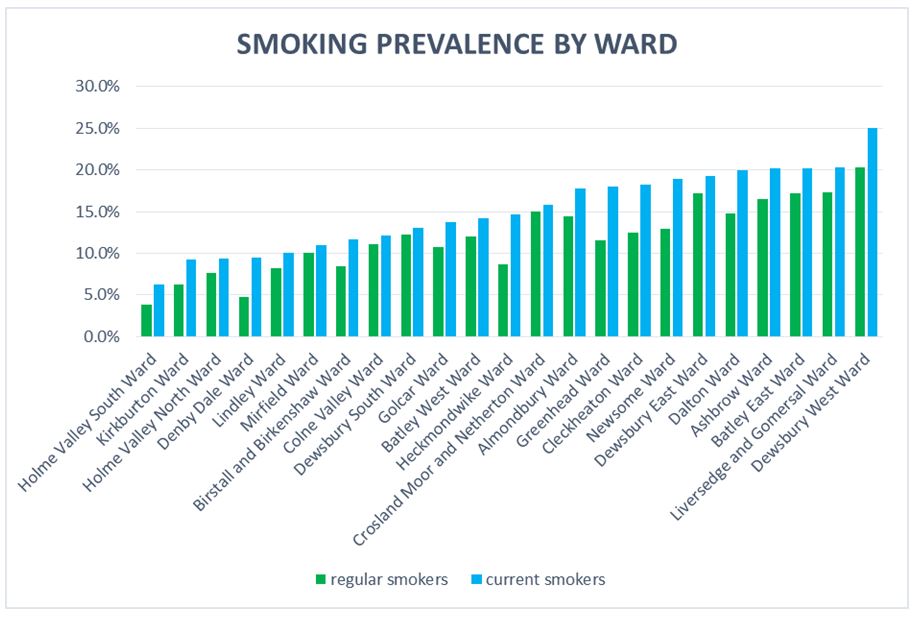

Within Kirklees, the prevalence of smoking varies greatly by place. In 2016 (12), as in 2008 and 2012, Dewsbury West had the highest levels of adults smoking, with 1 in 4 (24%) being current smokers and 1 in 5 (20%) regular smokers. Holme Valley South has the lowest level of smokers, with 6.2% of adults smoking and 3.9% regularly smoking.

These differences by geography also tend to correspond with differences in socio-economic factors: smoking is more prevalent in more deprived areas. 19% (1 in 5) of people living in the most deprived areas of the District smoke regularly, compared to just 3% (1 in 30) of those living in the least deprived areas (12).

Tobacco: Views of local people

In February 2017, Kirklees Council generated insight to inform the development of an effective, person-centred Integrated Wellness Model in Kirklees, particularly for adults who are least motivated to look after their health proactively. The adults who were interviewed highlighted that they had adopted behaviours like smoking as means of coping (26):

‘It’s ten minute for me to take for myself.’ Female, age 25 – 34 on how smoking helps with work and the kids.

In 2008, research was undertaken to understand why routine and manual workers smoke in Kirklees (27).

“My mum smokes, my dad smokes, my mum’s boyfriend smokes, my grandma smokes, my auntie smokes ….” (young male smoker, Batley)*

Local insight from Batley has highlighted key issues for residents in routine and manual occupations regarding reasons for continuing to smoke and/or barriers to wanting to stop.

- Insight from the routine and manual group shows that they gain more satisfaction from smoking than other life experiences.

- For men, being able to have a drink and a smoke with their friends and colleagues was seen as a ‘working class right’ and promoted group based relaxation.

- Smoking offered women ‘me time’, the opportunity to leave all their worries behind them, if only briefly, and time to be alone.

- These women disliked advertising that made them feel they were jeopardising the health and wellbeing of family members: “It doesn’t matter what advertising or leaflets or campaigning you do, people enjoy smoking.”

Tobacco: What could commissioners and service planners consider?

The Tobacco Control Plan for England was published in July (Department of Health, 2017), which highlights the importance of a Smokefree generation, a Smokefree pregnancy for all, parity of esteem for those with mental health problems and backing evidence based innovations to support people to quit smoking. It also sets clear, national determinations to achieve by 2020 which are –

- Reduce the number of 15 year olds who regularly smoke from 8% to 3% or less

- Reduce smoking among adults in England from 15.5% to 12% or less

- Reduce the inequality gap in smoking prevalence, between those in routine and manual occupations and the general population

- Reduce the prevalence of smoking in pregnancy from 10.5% to 6% or less

Commissioners and service planners need to think about offering a range of opportunities to support people to stop smoking and the government’s national ambitions:

- Effective services and therapies informed by national guidance and data intelligence.

- Supportive social networks and environments – campaigns, online and social media and promoting services in settings such as workplaces where employers provide the provision and support to help their employees quit smoking.

- Develop the evidence base of what works/needs to be implemented across the system to better support smoking cessation in pregnant women.

- Implement a joint partnership e-cig friendly policy for Kirklees.

- Create and promote Smokefree environments within communities.

- Continue to support the West Yorkshire wide illegal tobacco awareness and enforcement work.

- Design and commission health improvement services that are better integrated; supports and works with individuals holistically; and helps people to find solutions to things which influence their health and engagement in unhealthy behaviours such as smoking.

- Implement and promote Smokefree policies. Support the implementation of the tobacco CQUIN within NHS Trusts

- Work systemically to reduce tobacco prevalence within the following priority groups:

– Smokers in areas or population groups of high smoking prevalence.

– Women of childbearing age and pregnant women.

– Smokers with long term conditions including mental ill health.

– Smokers in secondary care and routine and manual workers.

- Work systemically to prevent the uptake of smoking in young people.

Tobacco: References

1) National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2015) Smoking: harm reduction Quality standard [QS92]. Accessed at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs92/chapter/introduction

2) NHS Digital (2018) Statistics on Smoking – England, 2018. Accessed at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-smoking/statistics-on-smoking-england-2018/content.

3) Department of Health (2017), Towards a Smokefree Generation: A Tobacco Control Plan for England. Accessed at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/towards-a-smoke-free-generation-tobacco-control-plan-for-england.

4) Royal College of Physicians (2010), Passive Smoking and Children. Accessed at: https://shop.rcplondon.ac.uk/products/passive-smoking-and-children?variant=6634905477.

5) Public Health England (2015) Smoking cessation in secure mental health settings. Guidance for commissioners. Accessed at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/432222/Smoking_Cessation_in_Secure_Mental_Health_Settings_-_guidance_for_commis….pdf

6) NHS Digital (2017) Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people England: 2016. Accessed at: https://files.digital.nhs.uk/07/49FE46/sdd-2016-rep-cor.pdf.

7) Office for National Statistics (2018) Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2017. Accessed at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/bulletins/adultsmokinghabitsingreatbritain/2017.

8) Public Health (2018), PHE publishes independent expert e-cigarettes evidence review. Accessed at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/phe-publishes-independent-expert-e-cigarettes-evidence-review.

9) Public Health England (2019), Vaping in England. Accessed at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vaping-in-england-an-evidence-update-february-2019/vaping-in-england-evidence-update-summary-february-2019

10) Action on Smoking and Health (2018), Use of e-cigarettes among young people in Great Britain. Accessed at: https://ash.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/YouthEcig2020.pdf

11) Public Health England (2015) E-cigarettes: an evidence update. A report commissioned by Public Health England. Accessed at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/733022/Ecigarettes_an_evidence_update_A_report_commissioned_by_Public_Health_England_FINAL.pdf.

12) Kirklees Council (2016), Current Living in Kirklees (CLiK) Survey 2016

13) Keep it Out (2018), Illegal Tobacco Keep it Out What is cheap or illegal tobacco? Accessed at: http://www.stop-illegal-tobacco.co.uk/illegal-tobacco/how-to-spot-it.

14) Smokefree Action Coalition (2017), Tackling half the difference. Reducing Health Inequalities: A Smokefree Action Coalition briefing for local authorities. Accessed at: http://smokefreeaction.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/BriefingInequalities.pdf

15) Local Government Association (2019), Press release: Illegal tobacco trade harming efforts to cut smoking, councils warn. Accessed at: https://www.wired-gov.net/wg/news.nsf/articles/LGA+Illegal+tobacco+trade+harming+efforts+to+cut+smoking+councils+warn+17052016134000

16) Public Health England (2018), Press release: Four in 10 smokers incorrectly think nicotine causes cancer. Accessed at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/four-in-10-smokers-incorrectly-think-nicotine-causes-cancer

17) Locala (2018), Case study for stop smoking service within current community based provision.

18) Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2018), Annual Population Survey 2018.

19) Public Health England, Local Tobacco Control Profiles. Accessed at: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/tobacco-control/data#page/0/gid/1938132885/pat/6/par/E12000003/ati/102/are/E08000034

20) Public Health (2015) Guidance Health matters: smoking and quitting in England. Accessed at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-smoking-and-quitting-in-england/smoking-and-quitting-in-england.

21) Kirklees Council (2019), Kirklees Young People’s Survey 2019.

22) Calderdale & Huddersfield Foundation Trust, Mid-Yorkshire Health Trust, Maternity Statistics 2017/18.

23) Public Health England (2016), Smokefree mental health services in England: Implementation document for providers of mental health services

24) NHS Digital (2018), GP Patient Survey 2018.

25) Kirklees Council (2018) Kirklees Mental Health and Wellbeing Needs Assessment. Accessed at: https://www.kirklees.gov.uk/beta/delivering-services/pdf/HNA-report.pdf

26) Kirklees Council (2017) Wellness Model Insight Generation, Final Report.

27) Kirklees Council (2008), Smoking in Kirklees Report

Tobacco: Date this section was last reviewed

July 2019, PG/RC

Data on young people updated April 2020, DH

Alcohol: Headlines

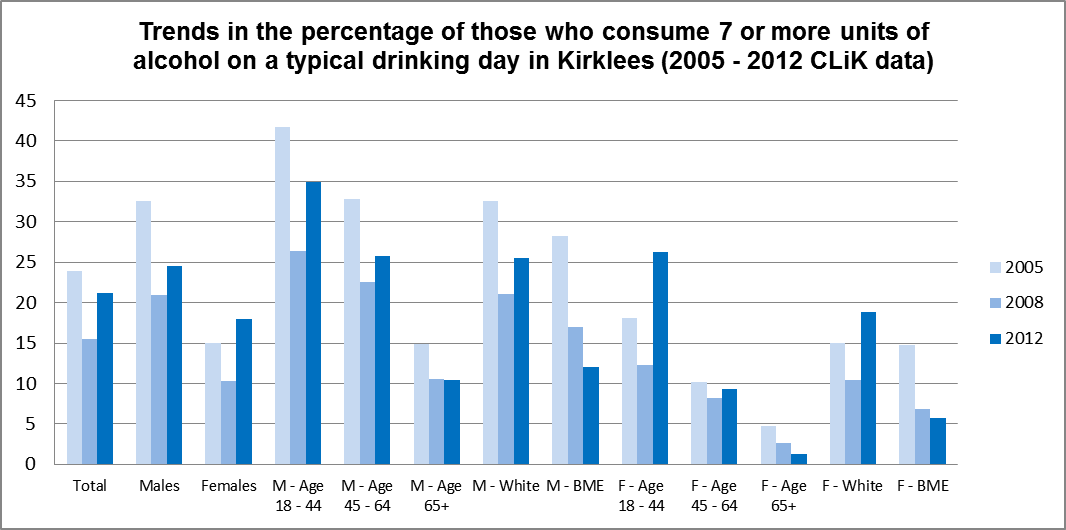

Kirklees has higher than average alcohol consumption and liver disease mortality rates in males. The local evidence identifies that those who are middle aged and have higher incomes are more likely to consume alcohol more frequently, but problematic drinking patterns (>7 units on a typical drinking day) are more prevalent in those with low household incomes, in those with routine and manual (R&M) occupations and 18-34 year old males and females. Those who binge drink are also more likely to smoke and take drugs. Over a third of women of childbearing age (WOCBA) and 20% of those with a long term condition drank in excess of the recommendations. Trends indicate that while males appear to be reducing their binge drinking habits, women of childbearing age appear to be binge drinking more than in 2005. The drinking behaviour of parents, carers and other family members is a strong influence on their children’s alcohol use. 4 out of 5 (82%) of those surveyed were not concerned about the amount of alcohol they consumed.

Alcohol: Why is this issue important?

Alcohol is the second biggest lifestyle health risk factor after tobacco use. Regularly drinking over the recommended daily limit can lead to short term (e.g. disturbed sleep, feeling stressed, memory loss) and long-term adverse effects (e.g. raised blood pressure and CHD, liver disease, cancers, mental health problems, stomach ulcers)1. Alcohol misuse is currently grouped into four areas: lower risk (recommended daily levels), increasing risk, higher risk and alcohol dependency2. Synthetic estimates for Kirklees from the Yorkshire public health observatory found that almost 1 in 4 (23%) of the population were “increasing risk drinkers” while 1 in 16 (6%) were “higher risk drinkers” and 1 in 20 (5%) were alcohol dependent3. Binge drinking in Kirklees (drinking 7 or more units for females/males on a typical drinking day) was 21%, similar to national figures of 1 in 5 (20%)3. It is estimated that alcohol is a factor in 1 in 3 (30%) sexual offences, 1 in 3 (33%) burglaries, and half of street crimes in the UK1. The 2011 “Your Place Your Say” survey5 found that approximately 1 in 3 (30%) respondents perceived drunk or rowdy behaviour as a problem in Kirklees5. Higher risk drinking also contributes to increased risky sexual behaviour, absenteeism, and drug misuse6. Whilst most 14-year olds in Kirklees do not drink, those that drink regularly are more likely to smoke and use illegal drugs7. Similarly, adults (especially 18-44 year olds) who binge drank were almost twice as likely to smoke, and 2.5 times more likely to have used illegal drugs in the last five years8.

In Kirklees, hospital admission rates for alcohol conditions and alcohol related death rates increased between 2006 and 2010 and alcohol related mortality (overall and liver disease) for males in Kirklees was higher than the regional and national average in 20109.

Alcohol: What significant factors are affecting this issue?

External and environmental factors such as the physical environment, work and income can influence the amounts and the manner in which people drink11. Alcohol was 69.4% more affordable in 2007 than it was in 198012 and Kirklees has the fifth highest number of licensed premises in Yorkshire and Humber3.

The local evidence identifies that those who have higher incomes and are in the least deprived IMD are more likely to consume alcohol above recommended drinking levels and less likely to abstain. However, problematic drinking patterns (>9 units on a typical drinking day) are more prevalent in those with low household incomes/within the most deprived IMD quintile8.

Alcohol: Which groups are most affected by this issue?

Children, young people and families

Alcohol drinking during any stage of childhood can harm a child’s development and young people who begin drinking before the age of 15 are more likely to experience problems related to their alcohol use15. The drinking behaviour of parents, carers and other family members is a strong influence on their children’s alcohol use and a family history of alcoholism is associated with an increased risk of alcoholism in children15. Locally, of 14-year olds who drank, over half (56%) reported their family as their primary source of alcohol with only 1 in 8 (12%) buying it for themselves7.

Adults: in Kirklees in 20128

- Only 7.4% of males and females did not drink any alcohol. Over half of those who were Asian did not drink alcohol in comparison to just 5% of those who were white.

- 60% of males and 40% of females drank alcohol at least 2-3 times per week. Those drinking alcohol more than four times a week were more likely to be aged between 45-64 and those earning in excess of £40,000.

- Those who were more likely to drink in excess of recommendations (<4 units on a typical drinking day) were households with an income greater than £20,000; males aged 25-34 (58%) and females aged 18-24 (58%); those in sales and customer service positions (64% M and 44% F); R&M males (56%) and females in managerial positions (42%).

- Those who were more likely to binge drink (>7 units on a typical drinking day) were males overall (33%) and females aged 18-44 (43%), male and female single parent (33%), obese males (31%), R&M males (35%), males working in skilled trade occupations (39%) and as process, plant or machine operatives (38%), and females working within sales and customer service occupations (24%).

- Overall, 82% of those surveyed were not concerned about the amount of alcohol they consumed whilst 12% were concerned and planned to reduce their intake.

Children and young people in Kirklees in 20097

- The age at which children have their first drink has essentially remained the same at 11.1 years (2007) to 11.5 years (2009).

- 2 in 3 (66%) children have tried alcohol by age 14, fewer than in 2007 (72%) and 2005 (84%).

Women of childbearing age (WOCBA: 18-44 years old)8

It is recognised that alcohol has detrimental effects on the health status of women of reproductive age and on the foetus, and locally, 1 in 4 (26%) of this group reported binge drinking. The majority of these women were white (29%), in the most deprived IMD category (37%), had a long-term limiting illness (31%) and workless (31%), and single (35%). For WOCBA with dependent children, 1 in 4 drank <7 units on a typical drinking day. Approximately 87% of this group were not concerned about the amount of alcohol they consumed. Of those who were concerned only 17% planned to reduce their alcohol consumption.

People with long-term limiting illness and specific long-term conditions (LTCs)8

1 in 5 (19%) of those with a long-term limiting condition drank at least 7 units on a typical drinking day. Overall, males with LTCs were more likely to drink more than females and people with depression and pain had higher than average drinking levels.

Healthy Foundations8

Those drinking below recommended alcohol guidelines were more likely to fall within the Health Conscious Realists (HCR) category; while those at or above the current alcohol guidelines were more likely to fall within the Live for Today (LFT), Unconfident Fatalists (UF) or Hedonistic Immortals (HI) categories. There are a proportion of those who do drink in excess of current Government guidelines but who fall within the HCR category, which may indicate that they are not aware that they are consuming alcohol at levels which are detrimental to their health.

Alcohol: Where is this causing greatest concern?

- Birstall & Birkenshaw (29%), Spen (29%) and Huddersfield South (27%) had the highest percentage of binge drinking in males and Huddersfield South (23%), Dewsbury (23%) and Birstall & Birkenshaw (21%) had the highest percentage of binge drinking in females. Furthermore, 32% and 34% of WOCBA in Birstall & Birkenshaw and Dewsbury binge drank.

- 84% of respondents in Dewsbury, Spen and Huddersfield South were unconcerned about the amount of alcohol they consumed and this figure rose to 90% of WOCBA in Spen and Dewsbury.

Local trends in alcohol consumption

Trends in alcohol consumption appear to have flattened out between 2005 and 2012 in those drinking at lower levels (data not shown). Those drinking at least 7 units on a typical drinking day has decreased in males (both white and BME males) while it has increased in females; especially in women of childbearing age.

Alcohol: Views of local people

Drinking at the outlined levels is viewed as the norm and local insight reflected that many local people consider Government health messages around alcohol unrealistic. Also, this insight identified limited recognition of specific long-term effects of excessive alcohol consumption and that peer pressure, along with habit, routine and boredom were all reasons teenagers and young adults choose to consume excessive alcohol.

Overall, certain subgroups of the population of Kirklees drink alcohol in excess of recommendations and this may have adverse public health and economic implications. There appears to be a significant proportion of women of childbearing age and people with certain long-term conditions who drink excessively. It would appear that the public still find the alcohol-related Government health messages confusing, are unaware of the long-term effects of excessive alcohol intake and believe that their drinking patterns are “normal” as 4 out of 5 people in Kirklees are unconcerned about their level of drinking.

Alcohol: What could commissioners and service planners consider?

Priorities for the Kirklees Alcohol Strategy include:

- Ongoing support for the development of work around earlier identification of alcohol misuse within primary care and other settings.

- Ongoing development work to skill up the wider frontline workforce across Kirklees to signpost, give brief advice and support, more targeted to needs.

- Significant work to engage acute hospital trusts more in accident and emergency and hospital-based alcohol services.

- More campaigns highlighting the effect of alcohol misuse in children, women of childbearing age and adult males.

- Consolidation of specialist treatment capacity for dependent drinkers.

- Development of a Liver Prevention Strategy to promote earlier diagnosis and treatment of liver disease.

- Support for minimum pricing and community safety initiatives to better manage the on and off trade and night-time economy.

Alcohol: References

- Drinkaware (ND). Available from: http://www.drinkaware.co.uk/ (accessed on 15th of January 2013.

- Department of Health. Signs for Improvement: Commissioning Interventions to Reduce Alcohol-related Harm. London: DH Publications; 2009.

- YHPHO. NHS Yorkshire and the Humber, Healthy Ambitions – Staying Healthy Alcohol Main and Alcohol Supporting Information; 2010. Available from: http://www.yhpho.org.uk/resource/item.aspx?RID=79123 (accessed on 6th of January 2013).

- Davies SC. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer, Volume One, 2011, On the State of the Public’s Health. London: Department of Health; 2012.

- Your Place – Your Say Survey; 2011.

- APHO. Technical Briefing 1; Sources of Data on Lifestyle Risk Factors in Local Populations; 2005. Available from: http://www.apho.org.uk/resource/item.aspx?RID=39441 (accessed 12 December 2012).

- Young People Survey; 2009.

- Ipsos Mori. Current Living in Kirklees Survey; 2012.

- North West Public Health Observatory (ND). Local Area Profiles for England: Kirklees.

- (WHO, 2001)

- HM Government. The Government’s Alcohol Strategy. The Stationery Office. London; 2012.

- ONS. Affordability of Alcohol in the UK. Trends in the Affordability of Alcohol in the UK; 2008.

- ONS. Smoking and Drinking Among Adults in 2009; A Report on the 2009 General Lifestyle Survey. London; 2011.

- Marmot. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England Post 2010; 2010.

- Kirklees Partnership. Joint Strategic Needs Assessment for Kirklees 2010. Health and Wellbeing. Key Issues for the People of Kirklees; 2011.

- WHO. Handbook for Action to Reduce Alcohol Related Harm; 2009. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/43320/E92820.pdf (accessed on 15th January 2013).

Alcohol: Date this section was last reviewed

22/07/2013 (PL)

Drug misuse: Headlines

Misuse of drugs is strongly associated with a range of physical and mental health problems such as blood borne viruses including hepatitis B and C and is strongly associated with a range of social issues including school absenteeism, safeguarding, troubled families, homelessness and unemployment. It can also lead to significant crime and disorder, affecting families, local communities, and local economies.

Drug misuse among adults and young people has fallen steadily in Kirklees, reflecting the national picture, and only 1 in 125 (0.8%) of the population aged 18 and over in 2010/11 used heroin and crack cocaine. Crack and heroin users represent an ageing population as fewer young people use Class A drugs, though there remain 460 people with the most serious problems outside treatment. Overall drug use in younger people and adults is falling. Cannabis remains the most popular drug used, though for the first time the Current Living in Kirklees (CLIK) survey has picked up use of “legal highs” which have been used by 24% of people who reported drug use in the last five years.

Drug misuse: Why is this issue important?

Drug misuse includes Class A drugs such as crack and heroin and also cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy and “legal highs”. It is associated with a range of health and social problems. Health problems can include mental ill health, blood borne viruses (HBV/HCV/HIV), earlier onset of age-related health conditions and poorer life expectancy. Smoking drugs and tobacco raises the risk of lung damage; a lifetime of drugs, alcohol and smoking raises the risk of cardiovascular disease for older drug users; undiagnosed or untreated hepatitis C can cause cirrhosis, liver failure, liver cancer and death; many injectors develop circulatory problems and deep vein thrombosis; arthritis and immobility are common among injectors.

Nationally about a third of the population admit taking illicit drugs at some stage in their lives and around 1 in 5 young adults say they have recently used drugs (mostly cannabis). Of the less than 2% of the population who have used opiates or crack in the past year, most will stop before they become addicted2. Increased risk of social problems is associated with dependent drug use, for example low educational attainment, limited employment experience, offending and homelessness. In short, drug misuse can blight lives and significantly limit life chances2.

Drug misuse: What significant factors are affecting this issue?

Demand for services and changing patterns of drug use

Kirklees has 2,572 problem drug users of heroin and crack cocaine (1 in 125, or 0.8% of the population) according to the last available estimate by the National Treatment Agency1. Of these, 860 were injecting drugs, 1,408 were in “effective treatment” in 2011/12 and 794 people in treatment reported having children. When engaged in treatment, people use fewer illegal drugs, commit less crime, improve their health, and manage their lives better – which also benefits the community1. The CLIK survey reports that 1 in 20 (7%) of Kirklees residents have used drugs in the last five years. Whilst 80% of this group have used cannabis and 5% heroin, the survey picked up use of “legal highs” by 24% of the drug-using group13. With little firm evidence about work and the health or community impact this is an emerging trend that needs to be addressed.

Mental health and offending behaviour

Occurrence of mental ill health amongst the drug treatment population is high with 3 in 4 experiencing one or more conditions4. The Kirklees dual diagnosis service currently supports 70 people with the severest co-morbidity of drug and mental health problems. Services for offenders have a long history of partnership working and integration in Kirklees and the Drug Intervention Programme works with 350 people in a partnership between treatment services and the Police.

Deprivation

The number of problematic drug users, admission rates for drug specific conditions and the number of individuals in contact with structured drug treatment services is closely linked to deprivation3. Most people accessing the adult treatment system are unemployed and not in education. Many have low basic skills, including literacy levels, and many are offenders or live in inappropriate accommodation5.

Hepatitis C

Injecting drug use and sharing of associated paraphernalia remains the greatest source of hepatitis C virus acquisition at 93%6. Transmission of HCV and HIV remains higher than in the late 1990s with 2 in 5 injecting drug users now infected with HCV and just over 1% with HIV6.

The development of community assets and social return

There are many local assets addressing the issue – recovery hubs in Dewsbury and Huddersfield provide peer-led support and aftercare and treatment services are popular with service users. Primary care services are increasingly an option as heroin use reduces. Drug services commissioning plans are engineering a shift towards recovery and re-integration for Class A drug users and “upstream” and therefore shorter interventions for younger substance users who are using cannabis, cocaine or legal highs. Building social capital at individual (self-help) and community levels (social care and family support) is designed to consolidate impact and we already know that for every £1 spent on interventions there is a social return of £5.831.

Drug misuse: Which groups are most affected by this issue?

Young people

The Government’s drug strategy says that specialist interventions should prevent young people’s drug and alcohol use from escalating, reduce harm young people cause themselves or others, and prevent them from becoming drug or alcohol-dependent adults. Specialist interventions in Kirklees are delivered according to a young person’s age, degree of vulnerability, and the severity of the problem. In 2011/12 164 children under 18 required support for substance misuse drug problems and over 90% were referred for help with cannabis and/or alcohol.

In 20098:

- 1 in 8 (12%) of all 14-year olds had tried illegal drugs – dropping from 2007 (16%) and 2005 (17%).

- Cannabis was the most tried drug; virtually all 14-year olds (94%) who had tried drugs had tried cannabis.

- Only 7.3% of those having tried drugs had been “out of control” monthly or more often.

- 163 young people under 18 are receiving support for drug misuse, primarily cannabis and alcohol.

Vulnerable young people

Vulnerable young people are at particular risk of substance misuse, especially looked-after children, young offenders, truants and pupils excluded from school, homeless young people and young people not in education, employment or training (NEET)9. Locally in 2008, half of local young people recorded as having a substance misuse issue were NEET and 1 in 7 young offenders required specialist treatment9.

Families and carers

Substance misuse by parents and/or other (significant) adults can strongly influence children. Nationally, 1 in 3 child protection plans and 62% of care proceedings were attributable to substance misuse. Effectively treating adults for substance misuse and supporting them to change their behaviour is a primary influence on their children’s behaviour9. There are estimated to be over 1,000 carers of substance misusers currently in treatment in Kirklees and in excess of 9,000 people living with misusers of all substances (including cannabis and alcohol)10. Carers often feel anxiety, depression, helplessness, anger and guilt associated with this11.

Drug misuse: Where is this causing greatest concern?

Both treatment and arrest data shows that adult drug use remains an issue in Huddersfield South. In 2008/9, 26% of those in Huddersfield South were in treatment, compared to 22% in Batley, Birstall & Birkenshaw, which had the highest percentage (24%) in 2007/8. Nearly 1 in 3 (31%) of those with a positive test for drugs at arrest lived in Huddersfield South, although for nearly 1 in 4 (23%) of those testing positive, their residence was unknown.

Fourteen year olds living in the Valleys reported the highest levels of occasional drug use (11% compared with a Kirklees average of 8%) and of monthly drug use (5% compared with a Kirklees average of 3%). Huddersfield South has the second highest rate of occasional drug use (9%) and Dewsbury the second highest rate of monthly drug use (4%).

Drug misuse: Views of local people

People in Kirklees are concerned about the relationship between drug use and crime. We also know that people who access treatment express good levels of satisfaction with their experience of treatment and support.

Drug misuse: What could commissioners and service planners consider?

The priorities are to engineer a shift, based on changing patterns of drug use, towards prevention and early intervention for non-dependent users, and recovery and re-integration for Class A drug users. This includes:

- Developing evidence-based interventions for young people in schools and other settings in accordance with emerging evidence.

- Developing segmented stepped care pathways into services that are based on supporting people as early as possible and as late as necessary.

- Ensuring that the whole system has a focus on recovery where necessary.

- Ensuring that the health needs of service users are being met, particularly around emotional health and wellbeing and blood borne viruses.

- Ensuring services are driven by quality standards, the evidence base and clinical effectiveness.

- Maintaining the focus on offenders and on the reduction of offending behaviour.

- Ensuring that parental problem drug and alcohol use and its impact on children is fully addressed by a more integrated approach to commissioning.

- Ensuring that people across Kirklees, from all backgrounds and localities, have equitable access to relevant services.

- Maintaining the focus on families and carers.

Drug misuse: References

- JSNA Support Pack for Strategic Partners for Adults and Young People, NTA 2013. SROI analysis; 2011.

- Centre for Drug Misuse Research, University of Glasgow. Estimates of the Prevalence of Opiate Use and/or Crack Cocaine Use in England 2008/9: Sweep 5 report; 2010.

- Marmot M. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England Post 2010; 2010. Available from: http://www.marmot-review.org.uk/

- Weaver et al. Co-morbidity of Substance Misuse and Mental Illness Collaborative Study (COSMIC). London: National Treatment Agency; 2002.

- National Treatment Agency. View It; 2009.

- Health Protection Agency, Health Protection Scotland, National Public Health Service for Wales, CDSC Northern Ireland, CRDHB. Shooting Up: Infections Among Injecting Drug Users in the United Kingdom 2008. An Update: October 2009. London: Health Protection Agency; 2009.

- Home Office. Hidden Harm – Responding to the Needs of Children of Problem Drug Users. London: Home Office; 2003.

- NHS Kirklees, Kirklees Council and West Yorkshire Police. Young People’s Survey (YPS); 2009.

- Cairns C. Hidden Harm: Safeguarding the Children of Substance Misusers in Kirklees: An Overview of Prevalence and Practice; 2009.

- Copello A, Templeton L, Powell J. Adult Family Members and Carers of Dependent Drug Users: Prevalence, Social Cost, Resource Savings and Treatment Responses. London: UK Drug Policy Commission; 2009.

- Orford et al. Coping with Alcohol and Drug Problems: The Experiences of Family Members in Three Contrasting Cultures. London: Taylor and Francis; 2005.

- Communities and Local Government. The Place Survey, England 2008; 2009.

- Currently Living in Kirklees Survey, IPSOS Mori; 2012.

Drug misuse: Date this section was last reviewed

09/07/2013 (PL)