Dying and bereavement

Dying and bereavement

Headlines

There were 11,040 deaths registered between 2013 and 2015. One in 100 were under the age of 20 (1%), 8 in 10 were aged 65 or over (84%) and 7 in 10 were aged 75 or over (67%). The major causes of death were cancer (more than 1 in 4 deaths, 27%), circulatory disease (more than 1 in 4 deaths, 27%) and respiratory disease (1 in 8 deaths, 13%).

The death of a child or the suicide of a partner or family member although rare can be very traumatic. Between 2010 and 2015 there were 291 deaths of people under the age of 20. There were 209 deaths from suicide and injury of undetermined intent in Kirklees between 2010 and 2015 (all ages).

People often struggle to discuss the sort of care or location of death they would prefer, and few people are clear about the options that might be available to them or their family members.

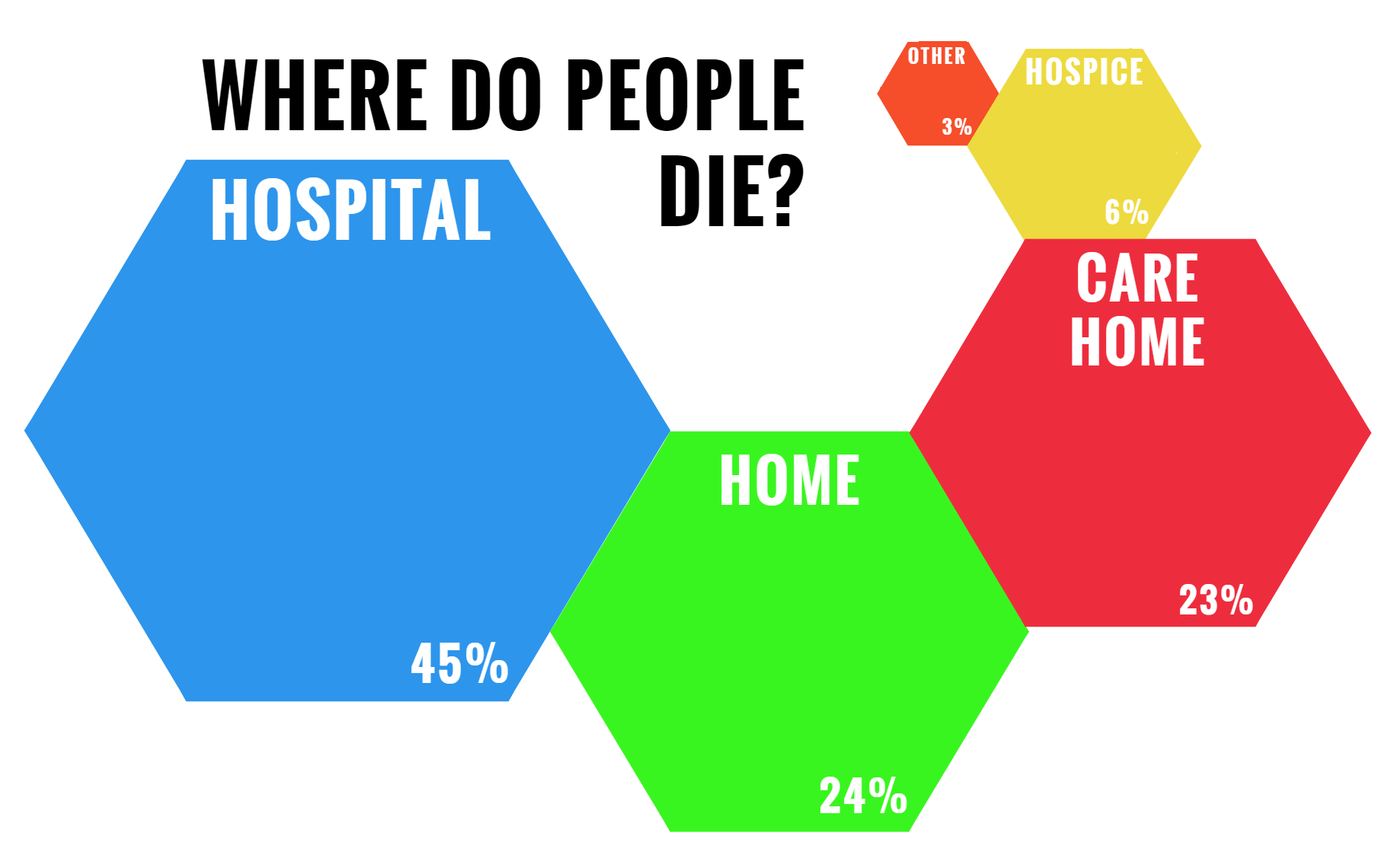

Most people in Kirklees die in hospital, although many people say they would choose to die at home or elsewhere. Bereavement and loss affects the family and friends of those who die in different ways.

Bereavement can reinforce or create financial difficulties, especially for women.

The impact of bereavement can lead to poorer health and even death in those who are bereaved. Women are more likely to suffer bereavement; however bereaved men are more likely to suffer negative impacts.

People dying where they want to and having the funeral they wished for can bring great comfort to those left behind.

Why is this issue important?

The majority of deaths occur following a period of chronic illness related to conditions such as cancer, heart disease, diabetes, stroke, chronic respiratory disease, liver disease, renal disease, neurological diseases or dementia (1). However, this is not always the case; there are a small number of deaths in childhood and young adulthood locally.

People that are dying should be able to choose where they die and there has been a shift in recent years to allow more people to exercise this choice. But the majority of deaths locally occur in hospital, which is where fewest people say they would prefer to die (2).

Hospital deaths 1,654 45.1%

Home deaths 870 23.7%

Care home deaths 833 22.7%

Hospice deaths 217 5.9%

Other places 95 2.59%

Data source: Public Health England End of Life Care Profiles (3)

In the UK the majority of the public want to be told if they are terminally ill. Effective communication by clinicians is generally seen as key to prevent misunderstanding and unnecessary distress and to ensure high quality palliative care (4). The person dying, as well as their friends and family, may find it difficult to talk about dying. This may be because many cultures avoid serious individual or collective consideration of death.

People tend not to be aware of the importance of discussing their wishes around death and dying. Advance care planning is a structured discussion between health and social care professionals with the dying person, and their family and carers about their wishes, needs and preferences for future treatment and support. It is underpinned by the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005 which applies to all elements of care provided to adults (5). These discussions are particularly important in progressive conditions such as dementia and neurological disease.

Death is a part of life; most people will experience bereavement at some point. Bereavement doesn’t just affect those later in life. Families and carers of people who have died suddenly and unexpectedly, such as through suicide or in an accident, may well have markedly different needs than those who die from a long term terminal condition.

Children who are bereaved of a parent, care giver or sibling can be particularly vulnerable. Children and young people often report feeling alone and different following the death of someone important in their lives. While no routine data are collected in the UK on this group, estimates suggest that, the majority of young people face the death of a close relative or friend, by the age of 16 when around 1 in 20 (4.7%) young people will have experienced the death of one or both of their parents and 1 in 16 have experienced the death of a friend (6).

There is a common misconception that children don’t grieve in the same way that adults do. All children will grieve when someone close dies, although each child’s reactions will be different. Grief is often disorganised and doesn’t always follow a set pattern of responses. Their reactions will depend on many things, including their age and their level of development (7).

Where someone is bereaved after caring for someone following a period of illness or a long term condition, it is important to understand the needs of the carer; the caring burden is physical, mental, emotional, and financial. Also, as most caregivers are spouses, they are often older themselves, with their own health issues. Family, especially spouses, have to cope with many issues which grow and intensify over time including ‘pre-death grief’, increasing physical aspects of care, and increasing levels of decision-making which are required when a loved one is dying (8).

Although bereavement affects a wide range of people, some of those most affected are the partners of the person who has died. In 2014 just over 3,600 people died in Kirklees – applying national rates this means that around 1,400 people who die locally leave a partner. It is important to note that this figure does not include cohabiting couples who are unmarried, or those who are divorced. Nationally around 220,000 couples in Great Britain are separated by death each year. Of these, 4 out of 5 are over state retirement age and 2 in 3 are women.

Bereaved people are at particular risk of poverty and problem debt. The death of a partner has been shown to be a trigger for claiming benefits and has been a reason for homelessness.

What significant factors are affecting this issue?

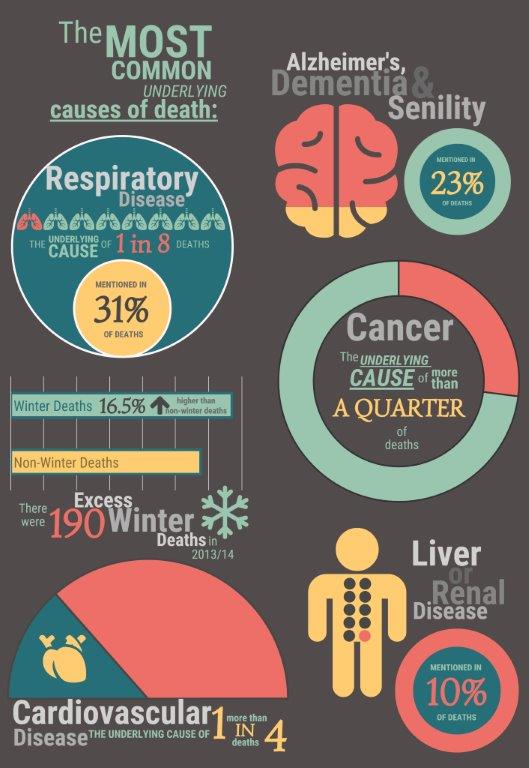

The most common underlying causes of death that are demanding end of life care in Kirklees (Primary Care Mortality Database, 2013-15) are:

-

- Cardiovascular disease – the underlying cause of more than 1 in 4 deaths (27%).

- Cancer – the underlying cause of more than 1 in 4 deaths (27%).

- Respiratory disease – the underlying cause of 1 in 8 deaths (13%) and mentioned in 1 in 3 deaths (31%).

- Alzheimer’s, dementia and senility – mentioned in nearly 1 in 4 deaths (23%).

- Liver or renal disease – mentioned in 1 in 10 deaths (10%).

- There were 190 excess winter deaths in 2013/14 in Kirklees, equating to 16.5% more deaths in winter compared with the non-winter period. Across England and Wales, the majority of excess winter deaths are associated with respiratory diseases, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and circulatory disease (9).

One of the aims of the national end of life strategy is to identify all those people who should be on an end of life register. Inclusion on an end of life register is linked to better co-ordination and quality of care for patients approaching end of life.

Around 0.29% of all Kirklees patients are on a GP practice Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF) “end of life” register, the same as regionally and nationally. This should be higher as around 1% of a GP practice population is likely to die on average each year i.e. meet the “3 trigger criteria” for inclusion on a register. This suggests that adults nearing the end of life diagnosed with chronic long-term illness are not gaining access to end of life care.

Approximately 40% of patients dying in acute hospitals do not have medical needs requiring a hospital stay (2). People, particularly care home residents, are frequently admitted to hospital towards the end of their lives “for often futile and distressing treatment” (10).

Those who are bereaved whether it was expected or not still have to go through a significant period of change and adaptation. Constructing a new identity and striving for independence in the face of changes to everyday activities and routines, loneliness, health concerns and changed relationships within the family and social network are essential features of older people’s bereavement experience (11). It is of course not just the spouse or care giver that experience grief, the death of an adult or child affects many individuals in different ways. It may be that psychological support is the primary issue for some bereaved people, but often it is a mixture of psychological support, practical support and time/space to comprehend and digest the loss they have experienced.

Financial hardship or stress following the death of a partner can hinder coping responses, increase likelihood of depressive symptoms and complicate adjustment to bereavement. How people cope with the consequences following the death of a partner may contribute to their emotional responses to bereavement. Psychological constituents of grieving, such as fear, anger, guilt and gaining new identities can all be affected by constructs of financial responsibility and economic wellbeing. These might include feelings about perceived economic roles of partner and self, feeling better off or worse off, or feeling more or less financially dependent (12).

Which groups are affected most by this issue?

Some studies suggest that older people are less likely to receive end of life care. Older people were shown to be more likely to die in hospital and nursing homes and less likely to die at home or in a hospice.

People with a learning disability are particularly affected because:

- They may find it hard to communicate or to understand what is being told to them. This may lead to people enduring pain for longer than they need to or missing medication because they have misunderstood how to take it.

- Receive fewer screening tests and fewer health investigations which lead to poor understanding of the individuals care needs.

- Particular presentations may be misinterpreted as a feature of someone’s learning disability leading to misdiagnosis or no diagnosis at all.

Religion, culture and language differences require close attention in order to be able to fully meet the needs of different individuals who are dying or bereaved; this extends further to families and communities where rituals and traditions become more important in advanced illness and at death.

Same sex partners may not have declared their status, with the consequence that professionals may exclude them from involvement in their partner’s care.

Women are less likely to die at home than men and men are generally less capable as carers (which is possibly the reason that less women die at home).

People who have experienced long-term homelessness (particularly rough sleeping) tend to die younger, whilst having the health problems of much older people and homeless people are less likely to engage with hospice based care (13).

Suicide is the leading cause of death among young people aged 20-34 years in the UK and it is considerably higher in men, with nearly four times as many men dying as a result of suicide compared to women (14). Between 2011-2013 the Kirklees suicide rate (3 year rolling average) was 8.6 per 100,000 population, but between 2013 and 2015 the rate in Kirklees has increased to 9.7 per 100,000 population (15). This increase is not statistically significant, and the rate in Kirklees for 2013-15 remains slightly below the equivalent regional and England rates (10.7 and 10.1 per 100,000, respectively).

Every life lost represents someone’s partner, child, friend or colleague, and their death will profoundly affect people in their family, workplace, club and residential neighbourhood.

This will impact their ability to work effectively (if at all), to continue with caring responsibilities and to have satisfying relationships. This will, in turn, significantly raise their risk of future mental ill-health and suicide. Unlike other major public health problems like cancer and coronary heart disease, suicide is most common in people of working age. And unlike cancer or heart disease, many people still find suicide difficult to talk about.

Where is this causing greatest concern?

People experience bereavement everywhere; however as described above the ability to cope both emotionally and financially following bereavement is linked to poverty and financial hardship. So those that are already experiencing poverty and financial hardship are likely to be even harder hit when they are bereaved.

What are the assets around the issue?

Health assets are those things that enhance the ability of individuals, communities and populations to maintain and sustain health and well-being. These include things like skills, capacity, knowledge, networks and connections, the effectiveness of groups and organisations and local physical and economic resources. They also include services or interventions that are already being provided or beginning to emerge which contribute to improved health and wellbeing outcomes.

Assets are hugely important to how we feel about ourselves, the strength of our social and community connections and how these shape our health and wellbeing.

As part of our KJSA development we are piloting a range of methods to capture and understand the assets that are active in Kirklees. Please see the assets overview section for more information about our approach and if you are interested in place-based information about assets in Kirklees have a look at the assets section in each of our District Committee summaries (Batley and Spen, Dewsbury and Mirfield, Huddersfield and Kirklees Rural). Where possible and appropriate we will provide information about local assets supporting people across different stages of the life course.

Some people who have been recently bereaved may be an inclined to get involved in more volunteering activities. The additional time that these people have on their hands is an asset that is being utilised at both a formal and informal level (16). People support activities in their local areas that are of interest to them, which can include contributing to organisations that support others who have been recently bereaved, and also supporting families and close neighbours.

People who are bereaved also take the opportunity to undertake activities that may benefit them as individuals; this could be learning new skills, taking up hobbies or a more general personal development to keep their minds active. These new and existing skills are sometimes put to use helping others. This could be through informal teaching, peer mentoring or more formal contributions to things like job applications and basic skills development in others.

Life experiences shape us all and individuals are often keen to help others going through similar life events, such as major life transitions, difficult circumstances such as money problems or job loss and experiencing illness or loss (17). This support is often rewarding for the individual as they feel people are benefiting from their experiences, and also the recipient feels two benefits: firstly that people have been through this before and also reassurance by the fact that someone really understands the situation that they are in.

What could commissioners and service planners consider?

Build on existing community assets

Commissioners, service planners and Councillors should consider local community assets such as those outlined above so that they can support and build on local strengths and also understand where there are gaps and unmet needs in particular places or amongst particular communities.

Discussions as end of life approaches

People, carers and their families should be encouraged to discuss their end of life needs as early as possible with relevant professionals. To enable this to happen, professionals need to feel able to broach this subject and have the skills to do this sensitively. This will facilitate the development of a timely co-ordinated care plan that most effectively meets their needs and wishes.

Further steps should be taken locally to tackle the taboo for the public and professionals about discussing death and dying as a life event.

Assessment, care planning and review and co-ordination of care

People nearing end of life should be identified and recorded in GP Practices so that a coordinated care plan can be put in place that can be shared by those staff and professionals supporting patients/ carers/ families both in and out of hours. People at the end of life should have a care coordinator identified.

Improve where necessary, end of life care for those in residential and nursing homes by developing targeted information and training for staff within residential and nursing care homes.

Learning, Evaluation and Improvement

Ensure that people are not prevented from dying in a place of their preference by process/systems barriers (e.g. lack of access to specialist equipment such as profiling beds).

Ensure that individuals, carers and their families’ experiences actively influence and shape local services.

Ensure professionals receive appropriate and effective education and training on an ongoing basis through a more co-ordinated approach across partners in Kirklees.

Supporting bereaved people

Ensure that recently bereaved people have timely access to information about relevant services such as bereavement support, financial advice and practical support. This should not be time limited and accessible for considerable time after bereavement (18).

The term postvention describes activities developed by, with, or for people who have been bereaved by suicide, to support their recovery and to prevent adverse outcomes, including suicide and suicidal ideation (19). On average, a single suicide intimately affects at least six other people (20). Between 2013 and 2015 there were 108 deaths in Kirklees through suicide, which equates to at least 650 people being closely affected by the suicide in Kirklees in this period. Resources should be made available to support those who are concerned about a family member, friend or colleague, such as ‘Help is at Hand’ (21).

References

- Department of Health. End of Life Care Strategy: promoting high quality care for adults at the end of their life [Internet]. 2008. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/end-of-life-care-strategy-promoting-high-quality-care-for-adults-at-the-end-of-their-life

- National Audit Office. End of Life Care [Internet]. 2008. Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/end-of-life-care/

- Public Health England. End of Life Care Profiles [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Oct 3]. Available from: http://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/end-of-life/

- Parry R, Seymour J, Whittaker B, Bird L, Cox K. Rapid Evidence Review: Pathways Focused on the Dying Phase in End of Life Care and Their Key Components. 2013;(March):1–35.

- The gold standards framework. Advance care planning [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/advance-care-planning

- Aynsley-Green A, Penny A, Richardson S. Bereavement in childhood: risks, consequences and responses. BMJ Support Palliat Care [Internet]. 2012; Available from: http://spcare.bmj.com/content/early/2012/01/03/bmjspcare-2011-000029.short?rss=1

- Fauth B, Thompson M, Penny A. Associations between childhood bereavement and children ’ s background , experiences and outcomes. Natl Child Bur [Internet]. 2009; Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.584.6512&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- The Choice in End of Life Care Programme Board. What’s important to me. A review of choice in end of life care [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/407244/CHOICE_REVIEW_FINAL_for_web.pdf

- Office for National Statistics. Excess Winter Mortality in England and Wales : 2014/15 (Provisional) and 2013/14 (Final) [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/excesswintermortalityinenglandandwales/201415provisionaland201314final

- Ahearn DJ, Jackson TB, McIlmoyle J, Weatherburn a J. Improving end of life care for nursing home residents: an analysis of hospital mortality and readmission rates. Postgrad Med J [Internet]. 2010;86(1013):131–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20237006

- Naef R, Ward R, Mahrer-Imhof R, Grande G. Characteristics of the bereavement experience of older persons after spousal loss: An integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(8):1108–21.

- Corden A, Hirst M, Nice K. Financial Implications of Death of a Partner [Internet]. 2008. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/research/pdf/Bereavement.pdf

- Age UK. End of Life Evidence Review [Internet]. 2013. Available from: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/health–wellbeing/rb_oct13_age_uk_end_of_life_evidence_review.pdf

- Office for National Statistics. What do we die from? [Internet]. 2015. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/mortality-statistics–deaths-registered-in-england-and-wales–series-dr-/2014/sty-what-do-we-die-from.html

- Public Health England. Suicide Prevention Profile [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Nov 9]. Available from: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile-group/mental-health/profile/suicide/

- Bussell H, Forbes D. Understanding the volunteer market: The what, where, who and why of volunteering. Int J Nonprofit Volunt Sect Mark [Internet]. 2002;7(3):244–57. Available from: https://research.tees.ac.uk/ws/files/6508628/58387.pdf

- The Centre for Welfare Reform. Peer support [Internet]. 2011. Available from: http://www.centreforwelfarereform.org/uploads/attachment/294/peer-support.pdf

- Kirklees Council; Kirkwood Hospice; Greater Huddersfield Clinical Commissioning Group; North Kirklees Clinical Commissioning Group. Kirklees Integrated End of Life Care Vision [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.kirklees.gov.uk/beta/adult-social-care-providers/pdf/kirklees-integrated-end-of-life-care-vision.pdf

- Andriessen K. Can postvention be prevention? Crisis. 2009;30(1):43–7.

- World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: A resource for general physicians [Internet]. 2000. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/56.pdf

- Support After Suicide. Help is at hand: Support after someone may have died by suicide [Internet]. 2015. Available from: http://supportaftersuicide.org.uk/help-is-at-hand/

Additional resources/links

National End of Life Care Intelligence Network:

http://www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/home

Kirkwood Hospice Quality Account 2015-16: https://www.kirkwoodhospice.co.uk/uploads/files/Kirkwood_Hospice_Quality_Account_2015-16.pdf

Date this section was last reviewed

09/11/16