Disabled Adults

Disabled Adults

Headlines

Why is this issue important?

People with a disability are a vulnerable group who experience significant inequalities in various aspects of their life. They have diverse needs; will often experience multiple health problems and may have difficulties communicating. People with disabilities can have poorer access to health care services and are less likely to take part in health screening programmes, leading to undiagnosed or untreated health problems and unmet healthcare needs.

(1)

(1)

What is disability?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) state that “Disability is … not just a health problem. It is a complex phenomenon, reflecting the interaction between features of a person’s body and features of the society in which he or she lives.” (2)

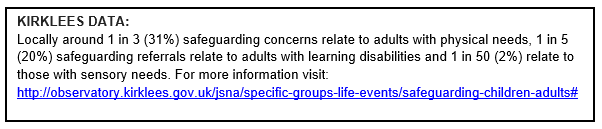

Under the Equality Act 2010, disability is defined as a “physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative impact on your ability to do normal daily activities.” Although impairments are long-term (lasting or expected to last 12 months or more), they can be permanent, temporary or recurring in nature. This definition encompasses a wide range of conditions, including:

Physical disabilities:

Physical disability is a long-term limitation (though not necessarily permanent) on a person’s physical functioning, mobility, dexterity or stamina. Such conditions may include: acquired brain injury; spinal cord injury; spina bifida; cerebral palsy; cystic fibrosis (CF); muscular dystrophy; dwarfism. This can also include physical conditions which limit other aspects of daily living, such as respiratory disorders, epilepsy, sleep disorders or Tourette syndrome.

Someone diagnosed with HIV, cancer or multiple sclerosis (MS) automatically meets the disability definition under the Equality Act 2010 from the day that they are diagnosed (3). However, many people with these conditions receiving effective treatment of in remission will live lives unaffected by their conditions and not consider themselves to be ‘disabled’.

Learning disabilities:

According to the learning disability charity Mencap, a learning disability is a reduced intellectual ability and difficulty with everyday activities – for example in household tasks, socialising or managing money. Learning disabilities are not the same as ‘learning difficulties’ which is a much broader group, and does not include specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia, dyspraxia, etc.

People with a learning disability tend to take longer to learn and may need support to develop new skills, understand complicated information and interact with other people. The level of support someone with a learning disability needs depends on the individual and is highly personal. Some may only have a mild learning disability and only need short-term, targeted support for specific things such as getting a job, whereas someone with a severe or profound learning disability may need full time care and support with every aspect of their lives (4).

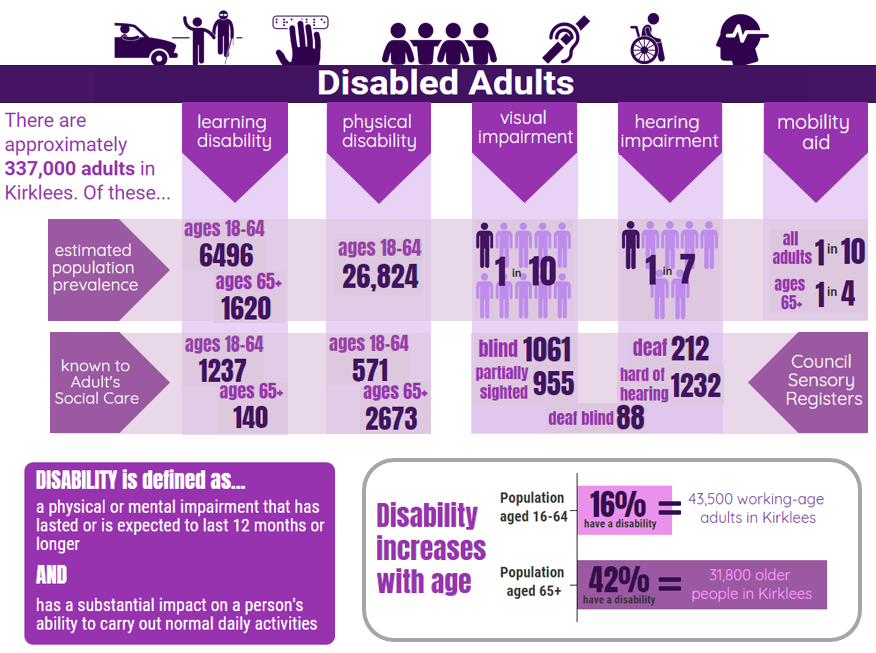

It is estimated that only 23% of adults with learning disabilities in England are identified as such on GP registers, the most comprehensive identification source within health or social services in England. The remaining 77% have been referred to as the ‘hidden majority’ of adults with learning disabilities who typically remain invisible in data collections (5).

Autism Spectrum Disorder (6):

Autism is a lifelong developmental disability that affects how people perceive the world around them and interact with others. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is the name for a range of similar conditions, including Asperger Syndrome, that affect a person’s social interaction, communication, interests and behaviour.

In children with ASD, the symptoms are present before three years of age, although a diagnosis can sometimes be made after the age of three. It’s estimated that about 1 in every 100 people in the UK has ASD. More boys are diagnosed with the condition than girls.

Some people with ASD enter adulthood without ever being diagnosed. However, getting a diagnosis as an adult can often help a person with ASD and their families understand the condition, and work out what type of advice and support they need. For example, a number of autism-specific services are available that provide adults with ASD with the help and support they need to live independently and find a job that matches their skills and abilities.

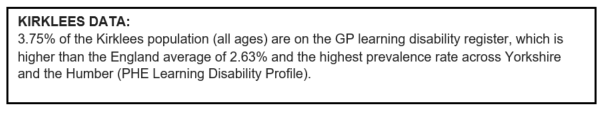

Visual impairments:

A person is said to be visually impaired when their sight loss cannot be corrected by glasses or contact lenses.

The main causes of sight impairment in Adults are:

- Age related macular degeneration

- Glaucoma

- Cataracts

Being certified as visually impaired or severely visually impaired allows people to register with the council. This is entirely voluntary and confidential, and means additional support can be accessed (7).

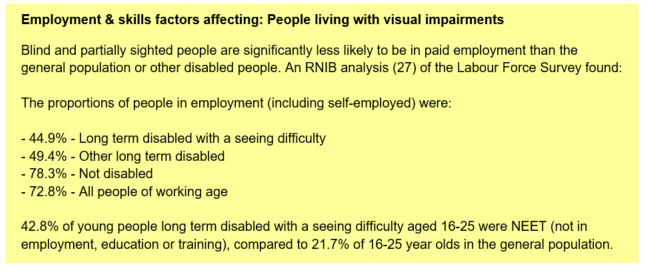

Sight loss can have a profound impact upon someone’s social, personal and work life. People who are blind/partially sight may experience, amongst other things:

- Barriers to employment

- Barriers to health and care services

- Feelings of isolation

Sight loss affects approximately 2 million people in the UK. Projections suggest that the number of people living with sight loss will increase by a third between now and 2030 to more than 2.7 million (8).

Hearing impairment:

A hearing impairment is a hearing loss that prevents a person from totally receiving sounds through the ear. Degrees of hearing loss can vary from mild to profound (when a person cannot hear anything at all). Some people are born deaf or become deaf before they learn to speak or use basic vocabulary. Others lose their hearing later in life and primary communicate through speech.

Mental health conditions:

Different mental health conditions may affect a person’s thinking, emotional state and behaviours, which can disrupt their ability to carry out daily activities, including work and maintaining personal relationships, and can therefore be classed as a disability.

For further information, see the Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing section of the KJSA and the Kirklees Mental Health and Wellbeing Needs Assessment.

You can find more information about older people and healthy ageing in the 2017/18 Director of Public Health Annual Report

Community assets and actions

What does an asset-based approach to disability look like?

An asset-based approach starts with ‘what’s strong’ rather than what’s wrong. Please see the assets section for more information about our approach to understanding assets in the KJSA.

An asset-based approach to disability involves recognising and supporting both personal assets of those with disabilities and community assets relating to disabilities, and enabling opportunities for these assets to grow. This will contribute to several of the seven Kirklees outcomes, particularly ‘people live independently and have control over their lives’, ‘people have aspiration and achieve their ambitions’ and people are as well as possible for as long as possible’.

There are a wide range of organisations and that are truly inclusive and reflect the wide range of people with and without disabilities locally. Increasing this inclusion is important and organisations across the public, private and voluntary sector should continue to remove boundaries for disabled people at strategic, operational and grassroots levels.

What are the community assets and action around disabled adults?

Health assets are those things that enhance the ability of individuals, communities and populations to maintain and sustain health and well-being. These include things like skills, capacity, knowledge, networks and connections, the effectiveness of groups and organisations and local physical and economic resources. Assets are hugely important to how we feel about ourselves, the strength of our social and community connections and how these shape our health and wellbeing.

The Council provides a range of disability support services. REAL Employment, which supports adults who have learning disabilities and additional needs into volunteering, training and employment, is a successful example of taking an assets-based approach to disability.

There is a wide-range of thriving community groups and organisations relating to disability in Kirklees.

Do Your Thing was a project which ran from 2015-17 and provided community based activities for people with learning disabilities and/or autism. The project had a focus on supporting people who are not eligible for services or are not using traditional services. 16 community based activity groups have been initiated as part of the project and are still running today.

Case studies: https://mailchi.mp/8fd656c02d27/enterprising-communities-project-call-for-pilot-sites-2479593?e=ef433c661e

Check the Community Directory for a full list of groups:

- Disability community support

- Visual impairment community support

- Hearing impairment community support

What significant factors are affecting this issue?

Safeguarding

Health and mortality

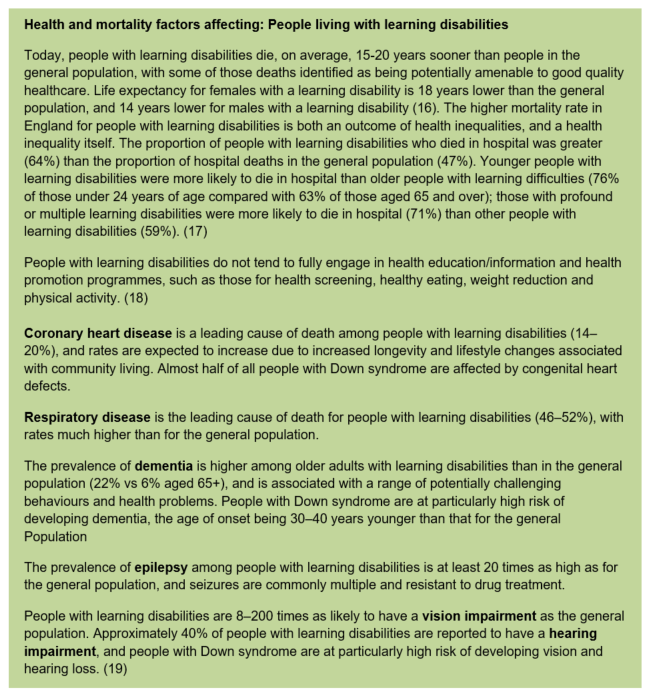

People with a disability will often experience multiple health problems and may have difficulties communicating. In addition people with disabilities can have poorer access to health care services and are less likely to take part in health screening programmes, leading to undiagnosed or untreated health problems and unmet healthcare needs. There is also evidence that obesity is more prevalent in the disabled population when compared to the general population (15).

Wellbeing & resilience

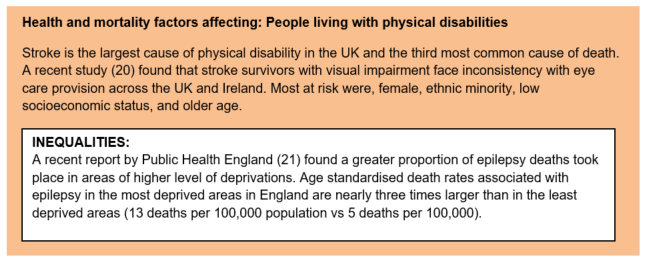

Mental wellbeing affects everyone across the life course. It is vitally important for the healthy functioning of families, communities and society. Together with resilience (the ability to ‘bounce back’ from difficult situations) it impacts on behaviour, social cohesion, social inclusion, and prosperity.

Disabled people in Kirklees are more than twice as likely as non-disabled people to report low wellbeing and are less likely to feel resilient:

Employment & Skills

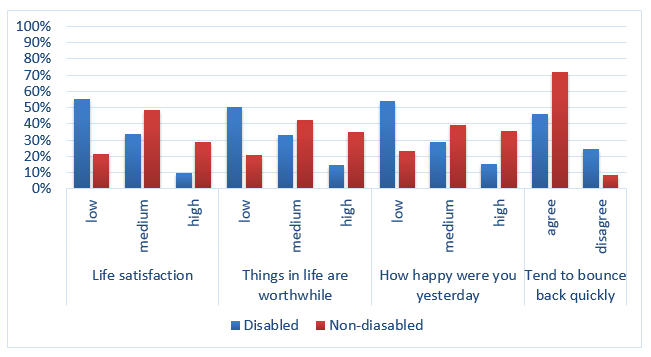

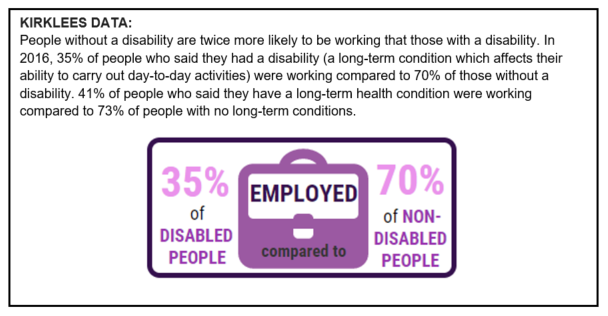

Poor health and disability is both a cause and consequence of unemployment. See the Work and Worklessness section for further information.

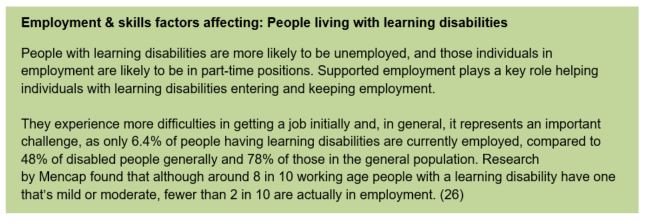

Disabled pupils have much lower attainment rates at school than non-disabled pupils, and are significantly more likely to be permanently or temporarily excluded. In 2014/15, the educational attainment of children with Special Educational Needs (SEN) was nearly three times lower than for non-disabled children. Across Britain in 2015/16, disabled young people aged 16-18 were at least twice as likely as their non-disabled peers to not be in education, employment or training (NEET). This has lifelong implications for people’s ability to obtain and sustain fulfilling employment (22).

There is a considerable ‘skills gap’ between disabled and non-disabled people when measured by qualifications. Only 15% of disabled people have a degree, compared with around 30% of non-disabled people. 15% of 25- to 29-year-old disabled people have no qualifications, compared with 6% of non-disabled people in the same age range (23).

Nationally, there were an estimated 3.9 million people of working age (16-64) with disabilities in employment in July-September 2018, meaning that around 120,000 more people with disabilities were in employment than a year previously. 51.3% of people with disabilities were in employment, up from 49.8% a year previously. The employment rate for people without disabilities was 81.4%. 393,000 people with disabilities were unemployed. These people were not in work and were actively seeking work. The unemployment rate for people with a disability was 9.3% in July-September 2018. This compared to an unemployment rate of 3.7% for people without disabilities. 3.3 million people with disabilities of working age were economically inactive. These people were not in work and not looking for work. People with disabilities were considerably more likely than those without disabilities to be economically inactive. While, the economic inactivity rate for those with disabilities was 44.4%, the corresponding figure for those without disabilities was 16.1% (24).

83% of disabled people acquire their disabilities while they are in work and approximately 300,000 people a year fall out of work due to health conditions. As susceptibility to disability increases with age, and our workforce continues to get older, more people will develop disabilities while working and risk losing their jobs (25).

Poverty & Income

Disabled people are more likely to be living in poverty than people without a disability (29): 31% of disabled people are in poverty compared to the UK average of 22%. 30% of families that include a disabled adult of child are in poverty compared to 10% of families that do not include a disabled adult or child.

Drivers of poverty for disabled people

Disabled people are more likely than non-disabled people to be disadvantaged in multiple aspects of life: these are problems in themselves and also contributing factors to poverty.

Low pay:

Low pay rates for disabled people are higher than those for non-disabled people, at 34% compared with 27%. This is the case at every level of qualification. For example, a disabled person with a degree is more likely to be low paid than a non-disabled person with a degree.

The disability pay gap in Britain continues to widen. In 2015-16 there was a gap in median hourly earnings: disabled people earned £9.85 compared with £11.41 for non-disabled people. Disabled young people (age 16-24) and disabled women had the lowest median hourly earnings (30).

Costs:

Disabled people face higher costs than non-disabled people, such as the cost of equipment to manage a condition. This means that the same level of income secures a lower standard of living than it would for a non-disabled person. There is evidence that ‘extra costs’ benefits such as Disability Living Allowance (DLA) and Personal Independence Payment (PIP) do not cover these extra costs sufficiently: in the bottom fifth of the income distribution, disabled people are more likely to be materially deprived, whether they receive extra costs benefits or not.

Social security benefits:

Social security benefits play an important role in supporting those unable to work, whether temporarily or over a longer time period, as well as mitigating some of the extra costs of disability. It has been the focus of policy reform for a number of years, with a redistribution of support within the disabled population and a greater degree of conditionality. Reform over recent years to long-term benefit claims saw a spike in the sanctioning of disabled people and consequent impacts on their quality of life and levels of poverty (31).

Access to services

Accessibility of services is problematic for disabled people, and they may be less likely to report positive experiences in accessing services. Poor access to transport, leisure and other services can affect the community and social life of disabled people, creating a barrier to independence and their enjoyment of day-to-day activities (32).

36% of adults with an impairment reported experiencing difficulty accessing public services, compared with 24% of adults without an impairment. The five most common public services where disabled people have tried to access, and consequently experienced difficulty, are: benefits and pension services (31%), social services (28%), health services (28%), tax services (26%), and justice services (23%). The most commonly reported barriers to accessing health services for adults with an impairment are: difficulties getting appointments (64%), difficulty making contact by phone (38%), unhelpful or inexperienced staff (25%) and difficulty with transport (13%) (33).

Loneliness & isolation

Loneliness is an emotionally distressing experience and for individuals who are chronically lonely, this can have significant impacts on longer-term mental and physical health (39).

A recent survey from Scope found that 67% of disabled people had felt lonely in the past year, with 45% of working age disabled people reporting chronic loneliness, saying they are always or often lonely (40).

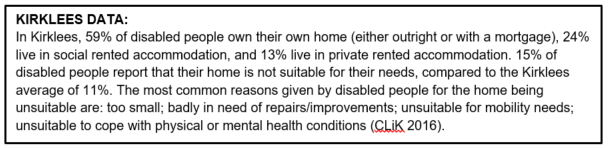

Accommodation & living arrangements

There is a national and local impetus to support more people to live as independently as possible in their own homes for as long as they can. This includes reducing the number of people placed in care homes and reducing the incidence and duration of hospital stays. Adapting homes to meet people’s needs where feasible is important.

However, there will always be a group of people who require some form of specialist accommodation commissioned or funded by the local authority who are not able to live in adapted general needs housing or have care needs that cannot be met by community support or home care. It is important to understand the long term needs and aspirations of disabled people around their living requirements to ensure that appropriate local solutions can be developed.

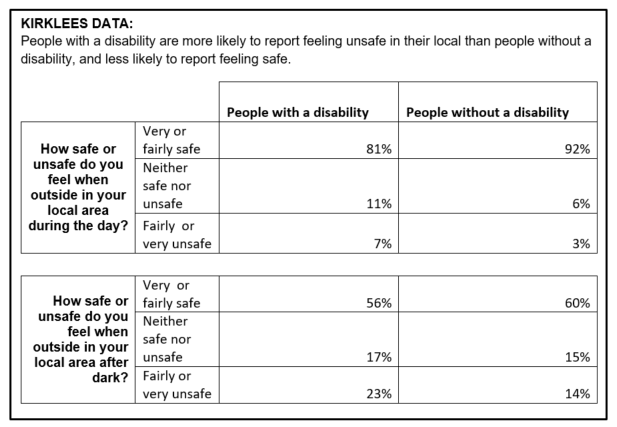

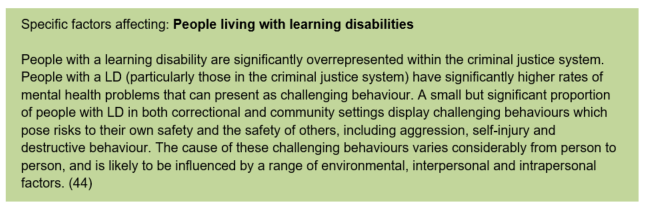

Crime

Disabled people are more likely to have experienced crime than non-disabled people. A report from the Equality and Human Rights Commission found that disabled people were more likely to feel unsafe walking alone in their local area during the day, and were more likely to report feeling worried about physical attack and acquisitive crime compared with non-disabled people (43).

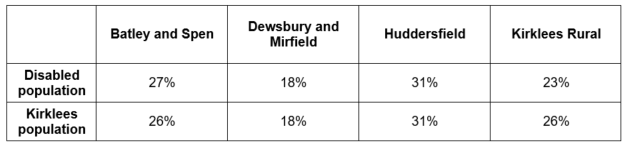

Where is this causing greatest concern?

There are people with disabilities living across all areas of Kirklees. The proportion of disabled people living in the four sub-districts of Kirklees is similar to the general population, with a slightly smaller proportion living in Kirklees Rural.

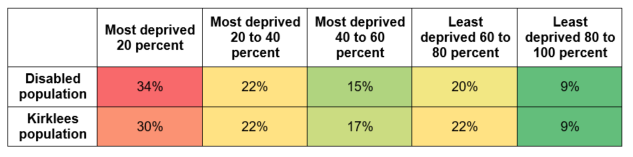

IMD Quintile

When we look at how the Kirklees population is spread over areas of deprivation, disabled people are slightly over-represented in the most deprived quintile compared to the general population:

Views of local people

Actively seeking the views of people with disabilities and their families is key to understanding their needs, concerns and views of current services and the existence and impact of local assets.

In addition to the findings from the CLiK surveys used throughout this section and the ‘Local Voice’ boxes in the ‘Access to services’ section above (see ‘What significant factors are affecting this issue?’), Healthwatch Kirklees have produced reports in recent years looking at local people’s views on disability services in the area:

- Wheelchair services

- Autism services

- Views on all age disability service

- Issues affecting people who are deaf or hard of hearing

What could commissioners and service planners consider?

Data and Intelligence:

- Use an evidence-informed approach – research consistently shows that early intervention and promoting resilience in disabled people can help to avoid the need for high-end intervention.

- Ensure a holistic approach is used to understanding the needs of people living with disabilities and their families.

- Develop a better local understanding of adults with autistic spectrum conditions.

- Develop a better understanding of the physical and mental/ emotional health of disabled people including health outcomes.

- Develop a coherent strategy for commissioning and developing services including information on what is on offer to disabled people.

- Address the under-reporting of learning disability and autism for people in the Criminal Justice System and the need for improved identification at the point of first contact. This will include those in custody, as well as offenders serving community sentences and those on probation.

Strength/ asset-based and place-based approaches

- Continue to learn with and from all partners and build the evidence of what works locally.

- Commission support that builds on existing strengths and assets that support disabled people and which responds to unmet needs in particular places or amongst particular communities.

- Ensure that health and social care services engage with disabled people in a holistic way and helps them find solutions to the things that determine their health and wellbeing.

Supporting families and carers across the life course

- Consider the mental health support of people with a disability and wellbeing support for families living with someone with a disability.

- Continue to develop emotional wellbeing support for disabled people and their carers.

- Work more closely with carers to understand their needs and expectations, and improve long-term planning particularly with older carers and parents of young disabled people entering adulthood.

- Preparing children and young people for the transition into adult life should start as early as possible. Planning for this transition should begin when a child is in Year 9 at school (13 or 14 years old) at the latest.

Access to services

- CCGs should work with Public Health England to ensure appropriate support is offered to individuals with a learning disability and/or autism to improve access to screening programmes. This should tackle issues around reasons for high refusal and non-attendance (DNA) rates and would include the provision of ‘easy read’ materials.

- Ensure that health improvement services such as smoking cessation, heath checks and support to be a healthy weight and physically active are accessible, inclusive and tailored towards the needs and assets of disabled people.

- Ensure care managers and commissioners of packages of support consider how assistive technology and telecare (AT&T) can be used part of a package of support.

- All people with learning disabilities with two or more long-term conditions (related to either physical or mental health) should have a local, named health care coordinator.

Housing & employment

- Build a strengths based approach to developing good home environments across support provision.

- People living with disabilities seeking social or supported housing should be offered a choice of housing, including small-scale supported living. Choice about housing should be offered early in any planning processes (e.g. in transition from childhood to adulthood, or in hospital discharge planning) and should be based on individual need and be an integral component of a person’s person-centred care and support. Where people live, who they live with, the location, the community and the built environment need to be understood from the individual perspective and at the outset of planning (45).

- Facilitate opportunities for supported employment for adults with learning disabilities entering and during employment.

Collaboration and engagement:

- Strengthen collaboration and information sharing, and effective communication, between different care providers or agencies.

- Ensure partnership working arrangements are in place, with Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) taking lead responsibility for the commissioning of specialist and general health services for people with disabilities.

- Ensure that people with disabilities, their families and carers are involved in the process of planning and decision making, so that their needs, choices and preferences are understood, and services are available to reflect individual choice and are the centre of service design.

Partnership workforce development

- Upskill and provide guidance for professionals to understand the emotional impacts of neglect and a lack of social integration for those who have disabilities.

- Ensure that front line practitioners are aware that changes in behaviour and mood can be a sign of an underlying medical condition.

- Acute services need to be supported in recognising the needs of patients with learning disabilities in their care, particularly people with communication difficulties who may present with certain behaviours as a mechanism to communicate.

- Work with colleagues in criminal justice to address and prevent hate crime and other forms of crime affecting disabled people.

- Work with colleagues in criminal justice to offer better support to disabled people in the justice system and to understand the underlying causes.

- Work with partner organisations and commissioned services to improve and encourage best practice ensuring there is a clear line of accountability.

Engagement with service users and carers:

- Remove physical barriers to access and make whatever alterations are necessary to policies, procedures, staff training and service delivery to ensure that they work equally well for people with learning disabilities, including:

- Improve employer awareness to support people with a disability in the workplace.

- Involve people with disabilities in the design, delivery, and evaluation of services.

- Removal of barriers that marginalise disabled people is the key to empowering disabled people, and giving them the opportunity to exercise their responsibilities as citizens – in the home, in the community and in the workplace.

References

1) Papworth Trust, “Disability in the United Kingdom: Facts and figures”, 2016 and 2018

2) World Health Organisation (WHO), “Disabilities”, web resource: http://www.who.int/topics/disabilities/en/

3) UK Gov, “Definition of disability under the Equality Act 2010”. Accessed at: https://www.gov.uk/definition-of-disability-under-equality-act-2010

4) Mencap, “What is a learning disability?”, web resource: https://www.mencap.org.uk/learning-disability-explained/what-learning-disability

5) PHE, “People with Learning Disabilities in England”, 2015. Accessed at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/613182/PWLDIE_2015_main_report_NB090517.pdf

6) NHS, “Conditions: Autism”, web resource: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/autism

7) RNIB, web resource:http://www.rnib.org.uk/eye-health-registering-your-sight-loss/criteria-certification

8) RNIB, “The State of the Nation Eye Health”, 2016. Accessed at: https://www.rnib.org.uk/sites/default/files/RNIB%20State%20of%20the%20Nation%20Report%202016%20pdf.pdf

9) RNIB, “Eye health and sight loss stats and facts”, April 2018. Accessed at: https://www.rnib.org.uk/professionals/knowledge-and-research-hub/key-information-and-statistics

10) Kirklees Council, Current Living in Kirklees survey, 2016.

11) London Assembly, “Mental health – disabled people and deaf people”, 2017. Accessed at: https://www.london.gov.uk/about-us/london-assembly/london-assembly-publications/mental-health-disabled-people-and-deaf-people

12) NHS, “Moving from children’s social care to adult’s social care”, web resource: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/social-care-and-support/transition-planning-disabled-young-people/

13) Council for Disabled Children, web resource: https://councilfordisabledchildren.org.uk/our-work/adulthood

14) Department for Work and Pensions, Family Resources Survey: 2015/16. Accessed at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/family-resources-survey-financial-year-201516

15) Robertson, J., Emerson, E, & Hatton, C., “Obesity and health behaviours of British adults with self-reported intellectual impairments: Cross sectional survey”, BMC Public Health, 14, 219, 2014

16) NHS, “Health and Care of People with Learning Disabilities: 2016 to 2017”. Accessed at: https://files.digital.nhs.uk/pdf/b/0/health_care_learning_disabilities_2016_17_summary.pdf

17) The Learning Disabilities Mortality Review (LeDeR) Programme, University of Bristol Norah Fry Centre for Disability Studies, Annual Report, December 2017

18) Emerson, E., Hatton, C., Roberston, J., Roberts, H., Baines, S., Evison, F., & Glover, G., “People with Learning Disabilities in England in 2011”, Durham: Improving Health and Lives: Learning Disabilities Observatory

19) Emerson, E., Baines, S., “Health inequalities and people with learning disabilities in the UK”, Tizard Learning Disability Review Volume 16 Issue 1 January, 2011

20) Hanna, K.L., Hepworth, L.R. & Rowe, F., “Screening Methods for Post-Stroke Visual Impairment: a systematic review”, Brain and Behaviour, Volume 7: Issue 5, May 2017

21) Public Health England, “Deaths Associated with Neurological Conditions in England, 2001 to 2014”, 2018. Accessed at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/683998/Deaths_associated_with_neurological_conditions_data_briefing.pdf

22) Equality and Human Rights Commission, “Being disabled in Britain: A journey less equal”, April 2017, accessed at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/being-disabled-in-britain.pdf

23) Tinson, A., Aldridge, H., Born, T.B. & Hughes, C., “Disability and poverty: Why disability must be at the centre of poverty reduction”, JRF/ New Policy Institute: August 2016

24) Powell, A., Briefing Paper: “People with disabilities in employment”, House of Commons Library, November 2018. Accessed at: https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-7540

25) The Centre for Social Justice, “Rethinking disability at work – Recommendations, polling data and key statistics”, March 2017

26) Mencap, Research and statistics: employment, web resource: https://www.mencap.org.uk/learning-disability-explained/research-and-statistics/employment

27) RNIB, “Investigation of data relating to blind and partially sighted people in the quarterly Labour Force Survey: October 2012 – September 2015”, 2016. Accessed at: https://www.rnib.org.uk/knowledge-and-research-hub-research-reports/employment-research/labour-force-survey-2015

28) Action on Hearing Loss, “Hidden disadvantage: why people with hearing loss are still losing out at work”, 2014. Accessed at: https://www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/how-we-help/information-and-resources/publications/research-reports/

29) Joseph Rowntree Foundation, “UK Poverty 2018”, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, December 2018. Accessed at: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/uk-poverty-2018

30) Equality and Human Rights Commission, “Being disabled in Britain – A journey less equal”, April 2017

31) Tinson et al., August 2016

32) Equality and Human Rights Commission, April 2017

33) Office for National Statistics, “Initial investigation into Subjective Well-being from the Opinions Survey”, 2011. Accessed: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_244488.pdf

34) Dr Truesdale, M & Professor Brown, M., “People with Learning Disabilities in Scotland: 2017 Health Needs Assessment Update Report”, School of Health and Social Care, Edinburgh Napier University: July 2017

35) NHS National End of Life Care Programme, “The route to success in end of life care – achieving quality for people with learning disabilities”, 2011

36) Popplewell, N.T.A., Rechel, B.P.D. & Abel, G.A., “How do adults with physical disability experience primary care? A nationwide cross-sectional survey of access among patients in England”, BMJ Open, 2014

37) RNIB, “Towards an inclusive health service”, 2009. Accessed at: https://www.rnib.org.uk/knowledge-and-research-hub/research-reports/general-research/towards-inclusive-health

38) Kirklees Blind and Low Vision Group, Visual Impairment Strategy: 2015 to 2020. Accessed at: https://www.kirklees.gov.uk/beta/adult-social-care-providers/pdf/kirklees-visual-impairment-strategy-2015-2020.pdf

39) A report by the disability charity Sense for the Jo Cox Commission , “‘Someone cares if I’m not there’: Addressing loneliness in disabled people”, 2017

40) Scope, Press release: “Nearly half of disabled people chronically lonely”, November 2017. Accessed at: https://www.scope.org.uk/press-releases/nearly-half-of-disabled-people-chronically-lonely?utm_content=bufferc7c3d&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter&utm_campaign=buffer

41) Mencap, survey of 18-35 year olds with a learning disability, 2015. Accessed at: https://www.mencap.org.uk/press-release/learning-disability-week-highlights-isolation-faced-young-people-learning-disability

42) National Autistic Society, “TMI Campaign Report”, 2016. Accessed at: https://www.autism.org.uk/get-involved/tmi/about/report.aspx

43) Equality and Human Rights Commission, April 2017

44) McClintock, K., Hall, S., & Oliver, C., “Risk markers associated with challenging behaviours in people with intellectual disabilities: A meta-analytic study”, Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47, 405-416, 2003

45) NHS England, “Supporting people with a learning disability and/or autism who display behaviour that challenges, including those with a mental health condition: Service model for commissioners of health and social care services”, October 2015. Accessed at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/service-model-291015.pdf

Date this section was last reviewed

December 2018, CP/RC