![]()

Child Sexual Exploitation: Victims, survivors and at risk individuals

Child Sexual Exploitation: Victims, survivors and at risk individuals

Headlines

Why is this issue important?

Child sexual exploitation (CSE) is a form of sexual abuse. The key factor that distinguishes CSE from other forms of child sexual abuse within the current policy framework is the presence of some form of exchange. The statutory definition is as follows:

“Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse. It occurs where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and/or (b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the perpetrator or facilitator. The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology.” (1)

CSE is not new. What is new is the level of awareness of the extent and scale of CSE and the growing number of ways in which perpetrators sexually exploit children and young people.

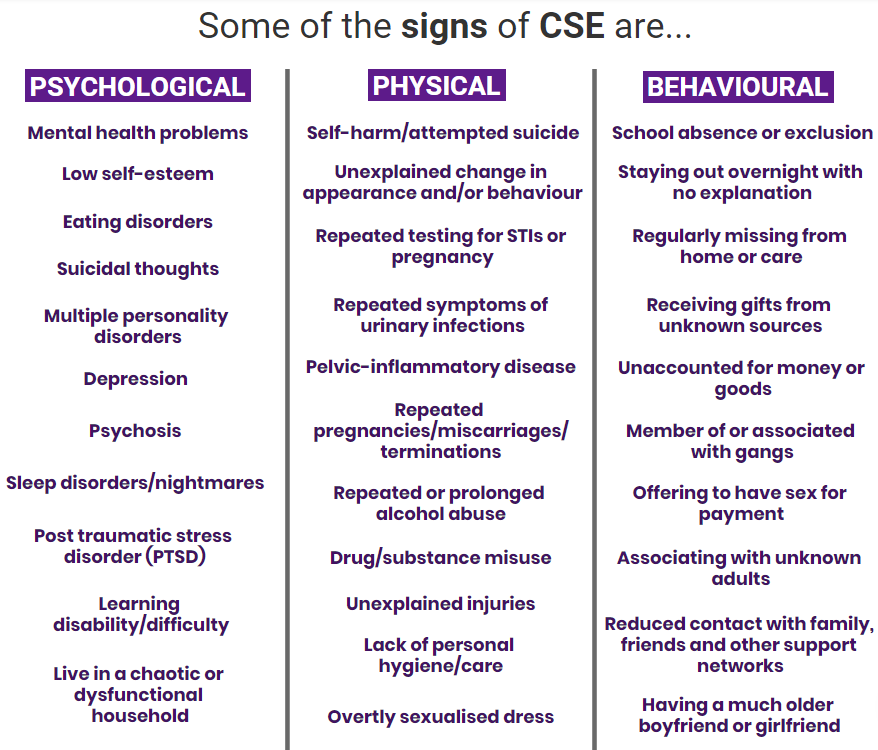

Sexual exploitation erodes the self-esteem of survivors, which can lead to acts of self-harm, such as self-inflicted injury, overdosing and eating disorders. It can put the young person at increased risk of sexually transmitted infections, unwanted pregnancy and abortion, as well as long-term sexual and reproductive health problems. It can affect the entire life course of the victim and those around them.

Studies have explored the relationship between childhood abuse and later health concerns. Research has found that childhood abuse contributes to the increased likelihood of depression, low self-esteem, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), problems with family functioning, anxiety disorders, addictions, personality disorders, eating disorders, sexual disorders and suicidal behaviour (2).

The negative impact of child abuse on adult mental health has been well documented; numerous studies have shown the link between child abuse and mental illness in later life (3). At present, there is no single diagnosis or condition that describes the psychological effects of child abuse. When in contact with mental health services, many adult survivors of child abuse find themselves diagnosed with multiple psychological conditions.

CSE can leave a legacy of trauma. The lives of CSE survivors might feature frequent crises, job disappointments, substance misuse, failed relationships, financial, housing and health setbacks. These can result from unresolved CSE issues preventing the establishment of regularity, predictability and consistency.

The effects or disclosure of CSE may not appear for months or years. There are likely to be adults who have been sexually exploited in the past and some who continue to be exploited. Some will have moved on with their lives and found their own way of coping with the trauma caused. Others will be in contact with support services to deal with the effects of CSE such as health issues, chaotic lifestyles, substance misuse and other complex problems.

The links between modern slavery, trafficking and child sexual exploitation

The UK Modern Slavery Act 2015 encompasses slavery, servitude, forced or compulsory labour and human trafficking. Modern slavery involves the use of force, deception or coercion to exploit someone to obtain some form of labour, crime or sex act. The Modern Slavery Act was intended to drive a more effective response to modern slavery and human trafficking (4). Recognition of the scale of child trafficking into as well as within the UK has grown as implementation of the National Referral Mechanism has revealed the numbers of children and young people being trafficked into the UK.

In 2017 in the UK, 5145 children were referred to the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) – a two thirds increase on 2016 (which was a two thirds increase on 2015). This is likely to be because of improved reporting but is still likely to under-represent the true scale of the issue. Trafficked children included 116 nationalities and the six most common countries of origin were Albania, Vietnam, China, United Kingdom, Nigeria and Romania. Currently the most commonly identified area of trafficking across Kirklees is child sexual exploitation (CSE). This affects both boys and girls and accounts for 1 in 4 (26%) of all trafficking reported via the NRM (5).

Some children and young people are trafficked into and outside Kirklees for the purposes of sexual exploitation. This includes children being moved around the region and further afield by their abusers or across networks of perpetrators.

Trafficked children are excluded from education, health and a safe and protective environment. Children are trafficked for a variety of purposes: sexual exploitation; forced labour; participation in criminal activities; child begging; child marriage; illegal adoption.

Sexual exploitation can become a means of control to prevent disclosure of other crimes, even if CSE was not the primary purpose of trafficking. Children may also become recruiters of other children, which compounds their sense of complicity and normalises the abuse.

Community Assets and Action

What would an asset-based approach to child sexual exploitation look like?

We should begin talking about a journey from being a victim to becoming a survivor. There are many reasons to use the term survivors rather than victims of CSE. The term ‘victim’ implies passivity, acceptance of circumstances, and the requirement to be treated differently. ‘Survivor’ reiterates the individual’s resilience, resourcefulness and the ability to take action in the face of adversity.

The effects of sexual exploitation can last long into adulthood. Recovery is possible but it is difficult and support is needed on the journey. This support can come from those who are already on the survivor journey, individuals who really understand the emotional impacts of CSE. These survivors are key assets in improving the support for new victims and working with professionals to eradicate the issue.

The strength of positive family relationships at home is a protective asset. Where family relationships are known to be poor, proactive work to strengthen this asset would be a useful preventative approach.

What are the community assets and action around this issue/ group?

There are a number of groups and networks in Kirklees who work with children and young people at risk of affected by CSE. Some, but not all, are listed in the Community Directly (a link to this is provided in the ‘people helping people’ section). Current examples include:

- Brian Jackson College (BJC) (in the Yorkshire Children Centre) work closely with young people and their families to address issues surrounding CSE. For example, they delivered “protect and respect” sessions with young people and their parents/carers during an open day at the college. These sessions provide support and guidance, looking at the warning signs and the risks surrounding CSE. BJC also support individual cases of suspected CSE and grooming, which have resulted in the young people being allocated CSE social workers and on one occasion resulting in a criminal conviction of a CSE perpetrator

- A community group called ‘Help the Creators’, based in Dalton, works with parents of children affected by multiple issues such as CSE, knife crime, drugs, mental health. https://www.facebook.com/parentsofteens/. This group works alongside a youth group in Dalton called ‘Keep it Real’.

- A group in Dewsbury Moor called ‘Trillz’ work with young people affected by/at risk of CSE. https://www.facebook.com/Trillz-Youth-Group-1825464297473186/

- The Base (run by CGL) provide a young person’s substance use service. They work with young people across Kirklees affected by CSE and substance use.

- There is a pathway and referral process in place between the CSE Hub and Kirklees Integrated Sexual Health Services (KISH). A designated ‘vulnerable’ young person’s clinic is held weekly in KISH to which CSE workers can refer young people.

There are likely to be many other community-based networks and sources of support for children and young people and their families affected by CSE in Kirklees although it is not necessarily their primary focus of concern and it is often the case that CSE remains hidden from families and communities.

For general information about the diverse range of community assets in Kirklees and links to additional resources please see the ‘people helping people’ section in the KJSA.

What significant factors are affecting this issue?

Many children face adversity at home, school and emotionally growing up. The difference with those affected by CSE is contact with a perpetrator. It is this same contact that leads to children being trafficked for sexual exploitation.

An internal review of local cases was undertaken in January 2016. Its purpose was to understand the journey of CSE victims and gain insights into the precursors to CSE and the personal impacts of the exploitation itself. Key findings from this review are outlined below:

Precursors to sexual exploitation

The home life of the victim including the behaviours of and relationships with other people at home all play a part in the likelihood of the victim becoming exploited. Emotional wellbeing and behaviour or anger issues featured in a high proportion of cases as both a cause and effect of poor relationships at home.

As well as difficult relationships between the victims and other people at home, the review found that parents or carers often had complex issues going on in their own lives such as domestic abuse, mental health issues, drug misuse and offending.

Multiple risks associated with suspected exploitation

The review found a number of risks/ issues to be present during or following potential instances of exploitation:

- The most common risk factor related to victims going missing with a large proportion of cases having repeated missing episodes. This was closely followed by absenteeism from school. This occurred in many cases, often escalating in frequency and duration as other risky behaviours such as offending, alcohol and substance misuse became more of a feature.

- Vulnerability through the internet was a factor in half of cases. Common tactics by perpetrators included online befriending followed by arranging to meet or threatening to distribute images after these were shared. Lack of awareness of parents of the risks posed by naïve use of the internet could increase risks to the victims.

- Poor emotional health and issues with self-esteem were seen in half of all cases as was self-harm and thoughts of or attempts at suicide.

- In some cases the child was already a victim of sexual abuse within the family or through familial connections. Amongst victims that had some learning disability, there were issues of coercion due to the increased vulnerability of these children and young people.

- Bereavement was a factor in some cases. Nationally, a loss of a role model or close relation is seen as an increased risk to vulnerability in potential CSE victims.

- Some of the cases were looked after children (LAC). Some LAC became victims because they were missing, in risky locations or misusing substances. Another group of LAC became looked after because they were involved in CSE and parents/ carers could not cope with or manage the child’s behaviours such as going missing, offending and substance misuse.

- In some cases, victims were, in effect, ‘recruited’ into exploitative relationships by other children.

There is no single type of grooming that can lead to exploitation. The review revealed circumstances ranging from online recruitment, being befriended by perpetrators whilst socialising with friends, to being recruited by friends into exploitative situations. It also showed that victims could be more vulnerable because of the locations they used socially. There were also examples of the ‘boyfriend model’ where a perceived normal sexual relationship becomes one of abuse or “sharing” the victim with other perpetrators in exchange for goods or as payment for other debts.

Nationally, around 40% of child sexual exploitation victims are caught committing offences, a proportion much higher than in the general population. Some victims of sexual exploitation are being punished by the criminal justice system for crimes they have committed in relation to their exploitation instead of being helped.

Victim recognition

Only in 1 in 10 victims were likely to acknowledge they had been exploited. The chaos around victims often masks the emotional effects of exploitation and instead factors such as being missing, absent, offending or misusing substances are predominant.

When it comes to disclosure, there are similarities in the obstacles faced by children who are being sexually abused and those who are trafficked. Children may not understand that feeling responsible for sexual abuse is a symptom of the abuse itself, and they may have carried this burden of shame for years. Many victims of sex trafficking who are later rescued report feelings of shame and a sense of personal responsibility over what happened. (6)

What does local data tell us?

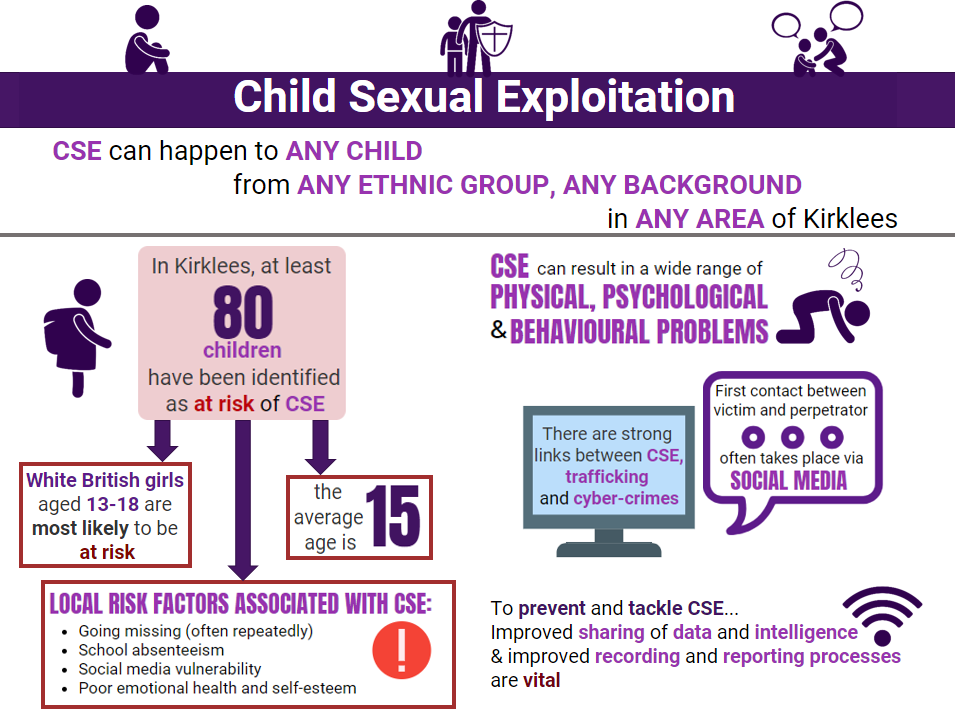

In addition to the valuable insights into CSE from the review of local cases highlighted above, we know that around 80 children in Kirklees are known to be experiencing varying degrees of risk of CSE. However this is likely to be only a fraction of the actual number of victims, due in part to issues of self-recognition/ definition.

What local data tells us about CSE offences, crimes and perpetrators

- CSE intelligence assessments produced by the Kirklees District Intelligence Unit of West Yorkshire Police show the number of offences per month specifically flagged as CSE (but see data/intelligence recommendations in section 9). Since November 2017 the number of current and historic offences recorded as CSE has varied from month to month, ranging from the highest of 35 (including 33 historic offences) to the lowest of three. It is often unclear which offences are cyber-enabled as, whilst many contacts between victim and perpetrator are initiated via social media they are not necessarily flagged as ‘cyber-enabled’ on the police system.

- Intelligence submissions to the police in relation to CSE are largely provided by the CSE Hub, gathered from the Youth Offending Team, Social Care and police officers/ staff who work closely with children at risk. Overall, CSE related intelligence submissions to the police have decreased by 55% since 2017.

- There are some ‘hotspots’ for CSE in both North and South Kirklees known to the police and this is valuable local intelligence. However, interpretation of the geographical distribution of CSE offences is problematic given that a large proportion of CSE offences in a given month may occur at a single address and that many CSE offences occur over social media.

- In October 2018 there were 139 people in Kirklees flagged as CSE ‘perpetrators’ on the police system. Many of these were being investigated under historic CSE investigations some of which have recently received local and national media attention.

- In Kirklees, the majority of perpetrators flagged on the police system are Asian men aged between 20 – 40 years. In October 2018, out of the known Kirklees residents, 35% of perpetrators resided in in the Huddersfield area (a decrease from 48% in January), 33% in the Batley & Spen area (an increase from 23% in January), 31% in Dewsbury & Mirfield (an increase from 24% in January) and <1% in the Rural area (a decrease from 5% in January).

- The majority of more recent offences could be defined as cyber-enabled because the initial contact between victim and suspect has taken place via social media, particularly Facebook.

What local data tells us about children ‘at risk’ of CSE

- In October 2018 there were 82 children (70 female and 12 male) in Kirklees flagged as ‘at risk’ of CSE on the police system. This has not fluctuated significantly over 2018 but the proportion of males has increased slightly from 7% in January 2018 to 15% in October 2018.

- It is important to note that the police flagging process is an ever changing picture as new ‘at risk’ children are added or removed on a daily basis and the risk levels (low, medium or high) may also change.

- In January 2018 the age of ‘at risk’ children ranged from 12-17 years and the average age was 15 years. The average age (15 years) has remained the same during 2018 although in July 2018 the age range had increased to include children from as young as 9 years old.

- The ethnic profile of ‘at risk’ children has changed slightly over 2018. Between January and October 2018 the proportion of ‘at risk’ children of white British ethnicity decreased very slightly from 58% to 56%, the proportion of children of Asian ethnicity increased from 11% to 18% and the proportion of children of Black ethnicity decreased from 10% to 7%. It will be useful to monitor this over the next 12-24 months.

- The proportion of ‘at risk’ children who are ‘looked after’ (either in foster care or a care home) has gradually increased over 2018 from 23% in January to 32% in October.

What the Kirklees Young People’s Survey 2018 tells us about related issues

- The majority (74%) of 14 year olds say they feel safe in their local area. A much smaller proportion of black ethnicity (51%) and LGBT+ (55%) 14 year olds say they feel safe.

- 90% of 14 year-olds use social media, with a third using it for more than 3 hours on a school day and nearly half using it for more than 3 hours a day on a weekend

- Girls are much more likely to use social media for 3+ hours than boys (37% compared to 23% on a school day and 51% compared to 36% on a weekend)

- 27% of 14 year-olds worry about some of the things they see on social media

- 1 in 10 (12%) want more information about staying safe online

- Some young people showed dependence on social media:

- 1 in 4 said their mood would be affected if they had to go a day without using it

- 14% said they worry about getting enough likes, with girls twice as likely to worry about this than boys

Which groups are affected most by this issue?

Any child or young person may be at risk of trafficking or sexual exploitation, regardless of their family background, social or other circumstances. This includes boys and young men as well as girls and young women. However, some groups are particularly vulnerable. These include those who have poor relationships at home, children who have a history of running away or of going missing from home or care, those with special needs, those in and leaving residential and foster care, children who have disengaged from education, children who are using drugs and alcohol, and those involved in crime. (1)

It is important to remember that CSE can occur in the absence of any known vulnerability factors with recent research indicating that this may be particularly true of online forms of abuse. (7)

We know from police data that most children flagged as ‘at risk’ of CSE have an average age of 15 years and are most likely to be white British girls. We know that almost a third of this cohort are looked after children. We also know that most ‘flagged’ perpetrators are Asian men aged 20-40 years. This has important implications for not only who we target for preventive and awareness-raising work but also how we manage potential community tensions, particularly in the light of recent high profile CSE investigations and prosecutions in Kirklees.

Information on transgender young people who have been trafficked is scarce. The NRM statistics have recently included a category for transgender victims, reporting three cases of ‘transgender’ trafficking and exploitation in 2017. However, transgender young people may identify themselves as something else. (5)

Where is this causing greatest concern?

- Anyone from anywhere can be a victim of sexual exploitation.

- CSE can happen to boys and girls.

- CSE can happen to young people of all ethnic groups and backgrounds.

- Whilst there are CSE ‘hotspots’ in Kirklees known to the police and the place of residence of CSE victims, ‘at risk’ children and perpetrators is also known (see section 5), CSE can take place anywhere and affects children in all parts of Kirklees.

- Police data shows that, in October 2018, of the flagged ‘at risk’ children residing in Kirklees, 35% lived in Dewsbury & Mirfield (an increase from 29% in January), 32% in Huddersfield (a decrease from 42% in January), 16% in Batley & Spen (the same as in January) and 16% in Rural (very small increase from 14% in January).

- It is important to be alert to the fact that different areas may experience different manifestations of CSE so local responses must be based on a local understanding of the issue.

Views of local people

The new Kirklees Neglect and Early Help Strategy Engagement Final Report (September 2017) (13) explores the views and perceptions of children and young people (CYP) on the issue of ‘neglect’. The report focuses on ‘wants’ and ‘needs’ rather than using the term ‘neglect’ and highlights a number of ‘needs’ perceived by CYP for emotional wellbeing. These included a loving, caring and supportive family; healthy self-esteem and confidence; positive role models; feeling safe in your environment and not being abused or bullied; and having clear boundaries and rules.

The views and perceptions of CYP on the issue of ‘staying safe’ were explored in a recent consultation exercise undertaken by IYCE on behalf of the Kirklees Safeguarding Children’s Board. CYP were asked to define what ‘staying safe’ means in the home, when out and about and when on the internet and social media. A range of views and experiences were captured from the consultation. Interestingly, CYP felt that guidance on how to stay safe on social media came largely from other CYP. A wide range of suggestions were given for the types of services that CYP think would meet their needs and keep them safe from harm, including training and awareness raising, advice and support and provision built into community hubs, youth provision and VCS organisations.

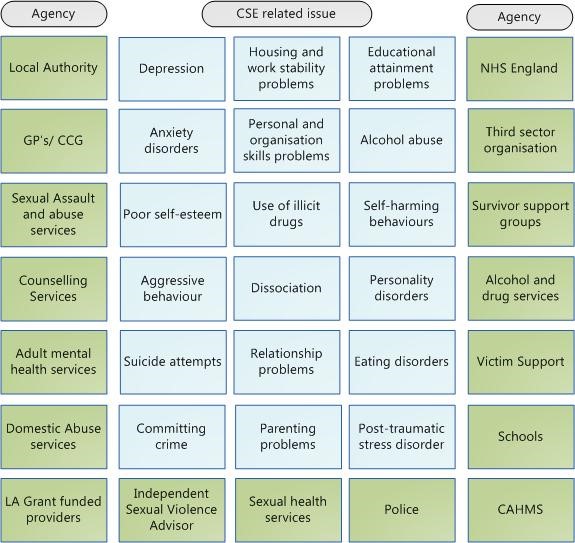

What could commissioners and service planners consider?

There is an important role for commissioners to connect together local intelligence on CSE, trafficking, missing children, slavery, extremism, domestic abuse, female genital mutilation and honour based violence. These share similar vulnerabilities, perpetrator methods and impacts on individuals. A useful framework based on an emerging evidence base and practice examples to support local leaders to establish a public health framework to address CSE has been developed by Public Health England (PHE). Some of the recommendations below are drawn from this report. Please refer to the PHE document for case studies and good practice examples. (7)

Understand

- Recording CSE – Due to the differing ways in which CSE can be recorded and presented on WY Police data systems it is difficult to ascertain whether all CSE data has been captured accurately. Not all potential CSE offences are flagged as such and some offences may be incorrectly flagged as CSE. Offences (including cyber-enabled CSE offences) need to be categorised more clearly in order to improve the analysis and interpretation of data on locations, perpetrators and victims.

- Data sharing – Support appropriate sharing of data, intelligence and insights between all relevant Kirklees partners in order to predict and prevent CSE, for example exploring Kirklees Council data and case studies alongside local police data on CSE incidents, victims and perpetrators to understand profiles, trends and patterns, risks and precursors. For example it will be useful to continue to monitor changes in the age and ethnic profile of children ‘at risk’ of CSE and the proportion who are currently ‘looked after’.

- Evidence-informed practice – Facilitate evidence-based commissioning/ delivery through the regular review and dissemination of evidence of ‘what works’ to prevent and reduce the short, medium and longer-term impacts of CSE. Learn from evidence based case studies and the additional resources highlighted in the PHE report (7), PHE Literature Search (15) and the LGA resource pack (8)

- Place-based knowledge and approaches – Given that different areas may experience different manifestations of CSE, local responses should be based on a local understanding of the issue. This is fundamental to ‘place-based working’. Kirklees partners could consider using the Place Standard tool (9) (recently piloted by Kirklees Council in the Golcar ward) to facilitate conversations with different communities in different neighbourhoods incorporating the topic of CSE risk/ prevention (sensitively and appropriately) into broader discussions around feeling safe, social contact, etc.

- Utilise available resources and toolkits for local authorities, councillors and partner agencies such as the LGA’s Tackling CSE Resource Pack (8).

- Using ‘voice’ -Ensure the views of children, young people and carers inform local strategies and service delivery. The insights from the IYCE ‘Staying Safe’ report [ref] provide a useful starting point.

Prevention and awareness

- Develop preventative services which reduce risk and raise awareness of CSE amongst children, young people, parents, carers and communities. Parenting support can facilitate better parent-child relationships which may prevent some of the family-based precursors to CSE.

- Work through schools, community hubs and parent-focused support networks to help teachers and parents to understand and have supportive conversations about social media, internet and mobile phone use and the potential CSE risks posed by social media. The insights from the IYCE ‘Staying Safe’ report (14) provide a useful starting point for discussions.

- Embed effective learning in schools to prevent CSE e.g. in Relationships and Sex Education and/or PHSE. An example of a whole school approach on CSE is highlighted in the PHE 2017 report.

- Ensure that all Kirklees Partners working with children and families are effectively incorporating CSE prevention and early intervention.

- Ensure that Public Health and Partner organisations join up and identify how social and built environment factors can be used to prevent and disrupt CSE (e.g. working with planning, licensing, Community Cohesion and Community Plus colleagues and the Voluntary and Community Sector).

Support for survivors and families

- Safeguard and promote the welfare of all children and young people who may have been or may be sexually exploited and ensure that they are properly supported in the course of and after criminal proceedings.

- A stable single relationship role – There could be significant value in a stable professional relationship as a part of a support offer. There is a need to replace the attention given to the survivor by the perpetrator with that from a person who the survivor can learn to trust and work with to make positive life choices.

- Support families and communities who are dealing with the consequences of CSE through effectively coordinated groups of professionals and community support networks. Partners and commissioners can work with Thriving Kirklees, Community Hubs, Community Plus and the VCS to help to identify, support and build on existing local community assets supporting children and families affected by CSE.

- Relationship re-building support – Where survivors are supported to reconnect with those from whom the CSE has isolated them; such as family members and friends.

- Develop community resilience to the potentially divisive and damaging impact of CSE on Kirklees and its constituent members.

Perpetrators

- Successfully prosecute those who perpetrate or facilitate CSE and enable the delivery of effective interventions to reduce the risk of further offending by perpetrators of CSE. The PHE CSE Literature Search (2017) (15) includes information on evidence-based interventions.

References and additional resources

1) Department for Education. (2017). Child sexual exploitation: definition and a guide for practitioners, local leaders and decision makers working to protect children from child sexual exploitation. Department for Education, (February), 23. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/591903/CSE_Guidance_Core_Document_13.02.2017.pdf

2) Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. (2014). Child Sexual Exploitation : Improving Recognition and Response in Health Settings.

3) Lazenbatt, A. (2010). The impact of abuse and neglect on the health and mental health of children and young people Anne Lazenbatt NSPCC Reader in Childhood Studies , Queen ’ s University Belfast Summary Key findings. Retrieved from: 238772406_The_impact_of_abuse_and_neglect_on_the_health_and_mental_health_of_children_and_young_people

4) Leon, L., & Raws, P. (2016). Boys Don’t Cry: Improving identification and disclosure of sexual exploitation of boys and young men trafficked to the UK, (March). Retrieved from

5) National Crime Agency. (2018). National Referral Mechanism Statistics-End of Year Summary 2017. Retrieved from: file (nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk)

6) The Howard League for Penal Reform. (2012). Out of place: The policing and criminalisation of sexually exploited girls and young women. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0264550512467593

7) Public Health England (PHE) (2017). Child sexual exploitation: How public health can support prevention and intervention. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/629315/PHE_child_exploitation_report.pdf

8) Local Government Association, Tackling child sexual exploitation: A resource pack for councils. Retrieved from: https://www.local.gov.uk/tackling-child-sexual-exploitation-resource-pack-councils

9) The Place Standard Tool. Retrieved from: https://placestandard.scot/

10) Beckett, H. 10 Key Facts about Child Sexual Exploitation. Video at: https://www.beds.ac.uk/ic/films. Text at: https://www.beds.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/510068/10-Key-Things-Film-briefing.pdf

11) Cancedda, A., De Micheli, B., Dimitrova, D., & Slot, B. (2015). Study on high-risk groups for trafficking in human beings – final report. https://doi.org/doi:10.2837/59533

12) Pyburn, S. (2018). Children Trafficked from Abroad: Understanding the dynamics of sexual abuse. Care Knowledge Special Report.

13) Kirklees Council IYCE Team (2017). Kirklees Neglect and Early Help Strategy Findings Report, September 2017. Accessed at: http://observatory.kirklees.gov.uk/Custom/Resources/Kirklees%20Neglect%20and%20Early%20Help%20Strategy%20Final%20Report.pdf

14) Kirklees Council IYCE Team (2018). Staying Safe Consultation Findings, September 2018. Accessed at: http://observatory.kirklees.gov.uk/Custom/Resources/Final%20Report%20Nov%202108%20KSCB%20Staying%20Safe%20Consultation%20Report.pdf

15) PHE Public Health England (PHE) (2017). Child sexual exploitation: How public health can support prevention and intervention. Literature search to identify the latest international research about effective interventions to prevent child sexual abuse and child sexual exploitation. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/626655/20170717_PHE_CSE_Report_Literature_search.pdf

Additional resources

Neglect Strategy 2018: https://www.safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Neglect-Strategy-2018-21.pdf

Kirklees Early Support Strategy, October 2018: http://www.kirkleessafeguardingchildren.co.uk/managed/File/Early%20Support/Early%20support%20partnership%20strategy%20(FINAL).pdf

Date this section was last reviewed

January 2019 (CP/HB)