![]()

Vulnerable Children

Vulnerable Children

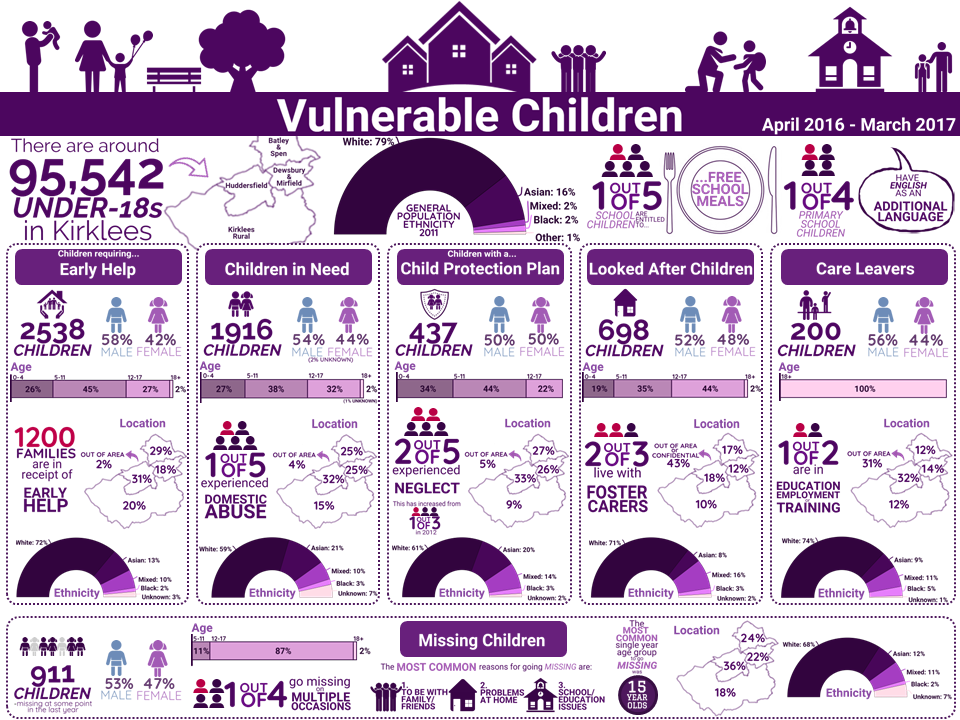

Headlines

Population Context

General 0-17 Kirklees Population |

|||

| GENDER | AGE (YEARS) | ||

| MALE | 51% | 0-4 | 29% |

| FEMALE | 49% | 5-11 | 39% |

| ETHNICITY | 12-17 | 32% | |

| WHITE | 79% | PLACE | |

| ASIAN | 16% | BATLEY & SPEN | 27% |

| MIXED | 2% | DEWSBURY & MIRFIELD | 20% |

| BLACK | 2% | HUDDERSFIELD | 31% |

| OTHER | 1% | KIRKLEES RURAL | 22% |

- Approximately 97,542 children and young people under the age of 18 years live in Kirklees. This is 22% of the total population in the area. (1) The number of under-18s is projected to increase by almost 9000 by 2030.

- 18% of primary school children and 19% of secondary school children are entitled to free school meals (FSM) (a proxy indicator for poverty) compared with 15% and 13% nationally. (2)

- 28% of primary school children and 22% of secondary school children have English as an additional language compared with 20% and 16% nationally. (2)

- The population of Kirklees continues to grow and diversify with projected increases in the youngest and oldest population groups putting a ‘squeeze’ on the working age population.

- There is a large variation in population ethnicity and new mothers’ ethnicity across Kirklees. For example in Dewsbury & Mirfield, just under one in five (18%) of the population is Pakistani and over one in three (35%) of births are to Pakistani mothers. In Batley & Spen the Pakistani population and birth proportions are 10% and 23% and in Huddersfield they are 13% and 23%. This means that the ethnic profile of the children’s population is changing significantly and will have important implications for schools and early help interventions.

- Some parts of Kirklees are much more deprived than others and this has important implications for how we tackle health inequalities. Virtually all key health indicators show a ‘social gradient. This means that children and families living in the most deprived areas in Kirklees are likely to have the worst health and wellbeing and the greatest need for help and support. Populations with a higher density of minority ethnic groups are associated with areas of higher deprivation.

- Infant mortality (IM) rates have declined both nationally and locally and the gap between Kirklees and England has reduced. However, IM remains higher in Kirklees than it is in the Y&H region and nationally and rates are highest in the Batley & Spen District Committee (DC) area. Rates of smoking in pregnancy vary across the district and are highest in non-South Asian women in Dewsbury and Batley. Breastfeeding rates are lowest in the most deprived areas and highest in the least deprived areas of Kirklees.

- School readiness is improving and is significantly better in girls than boys and in children who live in the least deprived parts of Kirklees. Almost two in three (65%) of all reception class children achieve a good level of development compared with only one in two (51%) of those who are eligible for FSM.

- The rates of healthy weight remain relatively stable overall in Kirklees with three out of four reception class children and two out of three year 6 pupils being recorded as a healthy weight. However obesity levels amongst children in both age groups living in the most deprived decile are double those living in the least deprived decile.

Vulnerable Children in Kirklees

There are children across Kirklees who are or become vulnerable for a number of reasons. This section describes the different groups of vulnerable children in Kirklees, many of which are defined in legislation; and outlines the range of issues that may be present in the lives of vulnerable children and their families. The vulnerable children described in this section are:

- Children in Early help

- Children with child protection plans

- Children in need

- Looked after children

- Care leavers

- Missing children

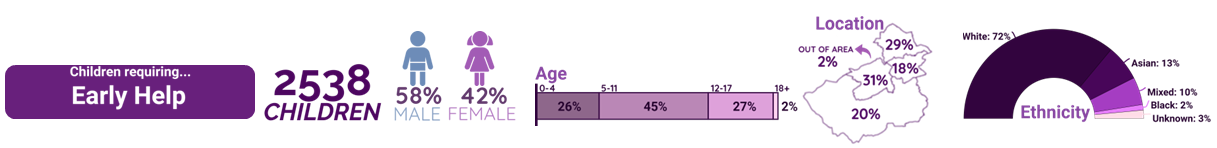

Figure 1 shows the number of children who fall within in each group of vulnerable children as at the 31st March 2017.

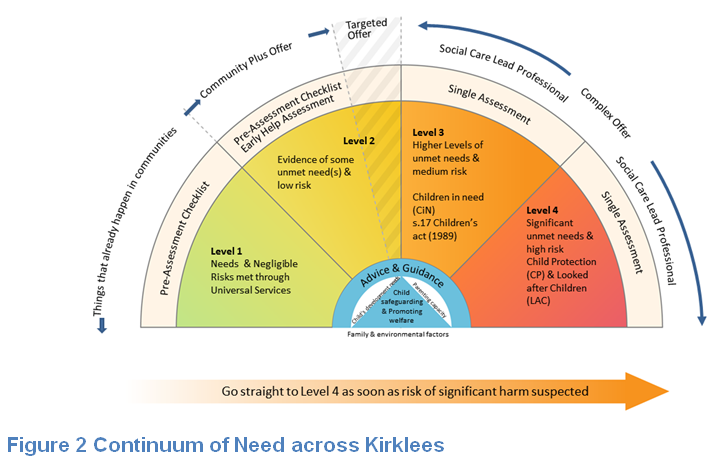

The continuum of need (figure 2) is a useful visual representation of the spectrum of needs of children across Kirklees. This ranges from ‘Level 1’ where needs are met through universal provision through to ‘Level 4’ where there are significant unmet needs and children are at high risk of harm.

Why is this issue important?

There are a number of children and young people who for a variety of reasons are vulnerable. It is important to understand and articulate their needs and their strengths. Children who have already experienced abuse or neglect are more vulnerable to being abused again. The most vulnerable children are at the most risk of further vulnerability.(3)

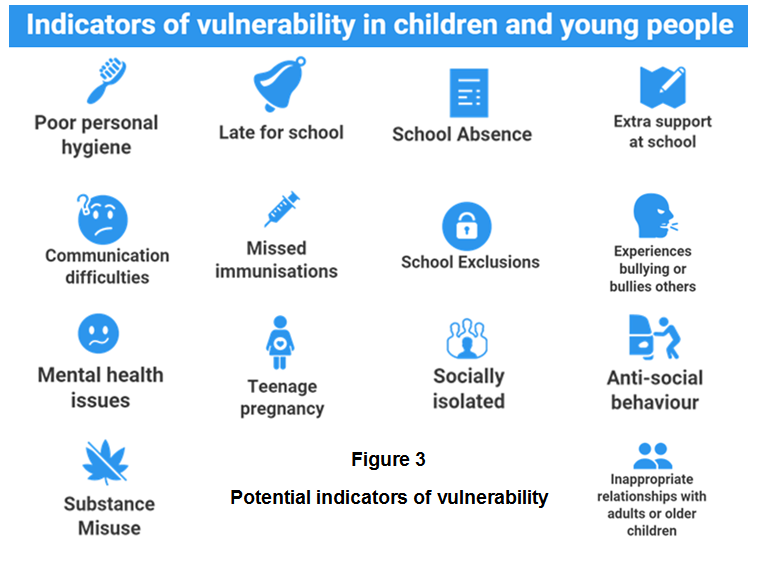

It is also important to understand the issues that affect those people in the household, family and social networks of vulnerable children as well as vulnerable children themselves, for example, where a child is a young carer for a vulnerable parent or sibling or there is domestic abuse in the household. Other indicators of vulnerability in children are illustrated in figure 3 and several useful resources for anyone who has concerns about a child can be found here.

Children and young people who are missing from home or care, absent from full-time school education and those at risk of sexual exploitation and trafficking have specific needs, some of which are outlined either in this section or elsewhere in the KJSA.

| A special note on: The life course impact of vulnerability

A vulnerable childhood can leave a legacy of trauma. The lives of these children might feature frequent crises, ill health, job disappointments, substance misuse, failed relationships, financial, housing and health setbacks. Many are the result of a failure to establish regularity, predictability and consistency. A range of studies (4) have explored the relationship between childhood neglect or abuse and later health concerns. Research has found that childhood abuse contributes to the increased likelihood of depression, low self-esteem, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), problems with family functioning, anxiety disorders, addictions, personality disorders, eating disorders, sexual disorders and suicidal behaviour.(5) Furthermore, child sexual abuse has been found to be a key factor in youth homelessness with between 50-70% of young people within supported accommodation having experienced childhood sexual abuse. The negative impact of child abuse on adult mental health has been well documented; numerous studies have shown the link between child abuse and mental illness in later life.(6) At present, there is no single diagnosis or condition that describes the psychological effects of child abuse and neglect. When in contact with mental health services, many adult survivors of child abuse and neglect find themselves diagnosed with multiple psychological conditions. |

What significant factors are affecting this issue?

There are many factors that contribute to a child becoming vulnerable. Many of these factors relate to the quality of care provided for the child, the environment where the child lives, available opportunities for learning and development and engagement in risky behaviours.

Quality of care

Several factors relating to the quality of care are indicators of child vulnerability:

- Basic care is not being provided

- Low parental aspirations

- Parent has been neglected or abused in their past

- Previous children have been removed

- Poor engagement with services

- Poor parenting skills

- Post-natal depression

- Poor relationships with extended family

| A special note on: Families with multiple or cross-generational issues

There are significant impacts on children if their parents are themselves experiencing ill health, hardship, abuse or other issues. Locally our ‘Stronger Families’ programme has built a detailed picture of the cohort of families experiencing multiple issues relating to the vulnerable children groups described in this section. This is not the full picture but gives an insight into the complexity of multiple issues within families. The ‘Stronger Families’ cohort is grouped under six specific domains:

Many of these issues are interdependent; 3 in 4 of the families with children in the cohort had issues in at least three of the domains above. The most commonly seen issue was worklessness, followed by missing education, domestic abuse and ill health. Children in early help – Of those in the early help cohort, 3 in 5 (1463) are also in the Stronger Families cohort. This cohort had more issues in the education and health domains than other levels of need. Children in need – Of those in the children in need cohort, 1 in 3 (852) are also in the Stronger Families cohort. Offending and domestic abuse is more common in this cohort compared to the early help cohort. Children with child protection plans – Of those in the child protection cohort, 2 in 3 (330) are also in the Stronger Families cohort. Offending, worklessness and domestic abuse are seen most often together in this cohort and at a higher level than early help and children in need cohorts. |

Pregnancy and maternal health of child and parent

Even before a baby is born there are things that parents do that influence the chances of the unborn baby being in poverty later in life. How a baby’s brain and its early skills develop is determined by its mother’s age, whether it is breastfed and whether it is being born into a safe and stable home with both parents. To find out more see the pregnancy and infancy section of the Kirklees Joint Strategic Assessment.

Protective early factors in a child’s life such as warm, positive and healthy parenting can help to create a strong foundation for the future; effective parenting can mitigate the effects of vulnerability by building resilience and positive self-esteem from an early age. Parental support and family stability can influence how well a child will do in school. Attainment levels in school subsequently affect life chances by determining employment options, income levels and general ability to integrate into society and develop mutually beneficial peer relationships.

Vulnerable young people may need additional support to avoid repeating their own experience of parenting and the cycle of poor attachment if they become parents themselves. It is therefore critically important that children in care and care leavers are enabled to gain the self-esteem and skills needed to develop loving, respectful and safe relationships.

| A special note on: Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is a procedure where the female genitals are deliberately cut, injured or changed, but where there is no medical reason for this to be done. FGM is usually carried out on young girls between infancy and the age of 15, most commonly before puberty starts. It is illegal in the UK and is child abuse. FGM is very painful and can seriously harm the health of women and girls. It can also cause long-term problems with sex, childbirth and mental health. There are no acceptable reasons that justify FGM. It is a harmful practice that is not required by any religion and there are no religious texts that advocate it. Altogether there are about 28 countries in Africa where FGM is practiced, in addition to Yemen and parts of Asia and the Middle East. The table below shows the number of women in Kirklees from these areas: |

||

Females Country of Birth |

All Females |

Females Aged 16-49 |

| North Africa | 290 | 217 |

| Central and West Africa | 301 | 268 |

| Middle East | 597 | 479 |

| Total | 1188 | 964 |

Domestic Abuse

Children’s experience of domestic violence in their home environment is recognised as a form of harm in itself. The impacts of domestic violence on children differ by developmental stage, but when children experience domestic violence in addition to other forms of abuse and neglect there is understood to be a high risk of emotional and psychological harm.(7)

Domestic violence can affect children’s behaviour and emotional well-being; cognitive abilities and development, and disrupt community, and family and friendship networks. To find out more please see the domestic abuse section of the Kirklees Joint Strategic Assessment.

Domestic violence and abuse is an important cause of long-term problems for children, families and communities. It has inter-generational consequences in terms of the repetition of abusive and violent behaviours. Witnessing domestic violence and abuse between parents irrespective of whether it results in direct physical harm to the child can have similar long-term consequences for a child to physical abuse that is targeted at the child.

The term “toxic trio” is often used to describe the interaction between domestic violence and abuse, mental ill-health and substance misuse which have been identified as features common in households where child maltreatment occurs. The presence of one, two or the entire ‘toxic trio’ is viewed as an indicator of increased risk of harm to children and young people. (8)

The impact of childhood exposure to domestic abuse is significant because of the link between domestic violence and child maltreatment and the association between exposure to domestic violence and juvenile and adult offending. The impact of domestic violence on children extends far beyond the impact of individual incidents, often making both victim and perpetrator emotionally unavailable to the child. Children witnessing domestic violence tend to have significantly more internalised (depression and anxiety) and externalised (aggression and anti-social) behavioural and emotional problems than children who are not in these abusive environments.(9)

| A special note on: Child Sexual Exploitation (CSE)

Child sexual exploitation (CSE) is a complex issue and the path into it is different for each victim. There are a number of precursors that may put children at increased vulnerability to exploitation. However, it can happen to any child from any family background in any area in Kirklees. The effects of CSE can be felt across the life course, not only in obvious ways like substance misuse, potential contact with the criminal justice system and employment issues. It also affects the ability of the victim to engage in new relationships, take care of themselves and relate to those around them. There are no robust numbers of CSE victims locally or nationally. This is because there is no single common factor or risk that can be measured. It is often a range of contributory circumstances affecting the child at a particular point in time. Whilst many children face adversity at home, school and emotionally growing up, the difference with those affected by CSE is contact with a perpetrator. There are two distinct groups of children that are of concern. Firstly, those who are likely to be experiencing key precursors to CSE such as poor parenting and home life, poor emotional wellbeing, domestic abuse and parental substance misuse. This is where preventative interventions would be beneficial to provide support and meet some of the needs of the child. The second group is children experiencing the risk factors associated with actual sexual exploitation which include; frequently going missing, frequently absent from school, estranged from family, vulnerable through the internet, offending, or a victim of prior sexual abuse. |

For additional details please see the CSE Section of the Kirklees Joint Strategic Assessment

Substance Misuse

Some children who enter care have been exposed to maladaptive pre-natal environments (e.g. through parental drug and alcohol abuse). The adverse impact of alcohol misuse during pregnancy is widely accepted and can result in irreversible neurological and physical abnormalities. Excessive alcohol use during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage and can cause Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD).(10)

Substance misuse also increases children’s vulnerability because of its impact on parenting capacity. Parental drug or alcohol misuse can result in parents having difficulty organising their lives, meeting their own and their children’s needs, and neglecting basic daily tasks. Parents may experience difficulty in controlling their emotions and severe mood swings can frighten children, leaving them feeling anxious and alone. Parental substance misuse may also affect the parent-child relationship when roles are reversed as children assume the physical and emotional care of their parent and younger siblings. (11)

Some families experience a combination of domestic violence, parental alcohol misuse, drug misuse, mental illness and learning disability. When domestic violence and parental substance misuse coexist, the effect on all aspects of children’s lives is more serious.

Nationally, the Hidden Harm report estimates that there are between 200,000 and 300,000 children in England and Wales where one or both parents have serious drug problems, representing about 2-3% of children under 16 years of age. Alcohol Concern suggests that there are likely to be some 800,000 children in England and Wales living in a family where a parent has an alcohol problem.(12)

Physical and emotional health

What happens during childhood influences adult well-being, risk taking behaviours, employment, and the development of ill health and disease. Childhood trauma can interfere with the stress response and the subsequent biological changes can fundamentally alter nervous, hormonal and immunological system development. These changes in childhood increase the risk in adulthood of heart disease, diabetes and premature death.(13)

Research (14) has shown that trauma and abuse (particularly sexual abuse) can have a detrimental impact on self-image. In national research, 16% of looked after young people were unhappy with their appearance. There was a statistically significant gender difference with 23% of girls in comparison with 7% of boys ‘hardly ever’ or ‘never’ liking their appearance.

Suicide is one of the main causes of mortality in young people and for families its impact is especially traumatic. A NCISH report showed that between 2003 and 2013, an average of 428 people aged under 25 years died by suicide in England per year. 137 were aged under 20 years and 60 were aged under 18 years. A history of abuse (physical, emotional or sexual) and/ or neglect was recorded in 20 people. Six had previously been under a Child Protection Plan or subject to a statutory order.(15)

Common themes in suicide by children and young people:

- Parental ill-health factors such as mental or physical illness

- Abuse and neglect

- Bereavement and experience of familial suicide

- Bullying

- Academic pressures, especially related to exams

- Social isolation or withdrawal

- Physical health conditions

- Alcohol and illicit drugs

- Mental ill health and self-harm

Teenagers who become parents are already known to experience greater educational, health and economic difficulties than young people who are not parents. Young people who have been looked after are two and a half times more likely to become pregnant as teenagers than the general population, and their children are then more than twice as likely to go into care themselves.(16)

Environment where the child lives

Accommodation and Housing

The large majority of the local vulnerable population lives at home, often whole families are being supported to ensure children do not progress further into the care system.

Overcrowding

Overcrowding is one of several aspects of housing conditions that have been found to be related to negative outcomes in health, education and childhood growth and development. Others include damp, mould growth, lack of basic amenities, housing type and tenure.

Nationally, the English Housing Survey (EHS) found that the overall rate of overcrowding in England in 2014-15 was 3%, unchanged from 2013-14, with 675,000 households living in overcrowded conditions.(17) Locally, in 2014, there were around 5,390 people in overcrowded accommodation according to the ‘bedroom standard’ model. Overcrowded properties are more common in urban centres than rural areas.(18) Living in crowded housing conditions can create stress in the home and have negative consequences for inhabitants. Children may be particularly vulnerable to the impacts of overcrowding because they use the space in the home to do homework, interact with family members, develop and practice skills, and sleep.

Special guardianship, Fostering, Residential Care & Adoption

Locally we use a variety of care arrangements for vulnerable children and young people who are unable to live at home temporarily or for the long term.

The common arrangements used include:

- A special guardianship order (SGO) is applicable in a wide range of situations; it has come to be used, in the main, to secure placements within the extended family network.

- Foster care can be short-term (e.g. in an emergency, for respite or assessment), intermediate (e.g. for treatment, preparation for independence or for adoption) or long-term. Long-term foster care can provide children with the security and stability they need until adulthood and is an important permanency option for many children.

- Residential Care refers to placements in children’s homes, residential schools, secure units and unregulated homes and hostels.

- An adoption order made by a court extinguishes the rights, duties and obligations of the natural parents or guardian (including the local authority) and gives them to the adopters.

Placement instability

Children’s experiences of abuse and neglect leave them at risk of having emotional, behavioural and mental health problems which can continue long after they have been removed from the adverse environment and placed with nurturing carers. This often manifests as problems with placements. In the year ending 31 March 2016, over two in three (68%) looked after children had one placement during the year, one in five (21%) had two placements and one in 10 (10%) had three or more placements.

| A special note on: Unaccompanied asylum seeker children

An asylum seeker is an individual who has applied for protection through the legal process of claiming asylum due to experiences of persecution in their country of origin. Trends in the origin of asylum seekers largely reflect current socio-political situations in the world. Unaccompanied asylum seeking children are some of the most vulnerable children in the country. They are alone in an unfamiliar country and are likely to be surrounded by people unable to speak their first language. They are likely to be uncertain or unaware of who to trust and of their rights. They may be unaware of their right to have a childhood. The local authority providing for their care has a duty to protect and support unaccompanied asylum seeking children. Because of the circumstances they have faced, unaccompanied children often have complex needs in addition to those faced by looked after children more generally. The special support required to address these needs should begin as soon as the child becomes looked after by the local authority. |

Opportunities for learning and development

Learning, Skills and NEET.

Vulnerable children face disadvantages that can have a significant limiting effect on their achievement and attainment as well as their broader outcomes. There is a clear gap between the educational attainment of the majority of children and those from vulnerable groups. Children who are looked after by the local authority are more likely to have poor experiences of education and very low educational achievement at school.(19) The proportion of looked after who reach the average levels of attainment expected at all ages remains significantly smaller than for other children and few progress on to higher education.

School is a vital social environment as well as an academic one, a place and time where children learn to be themselves and how to ‘fit in and join in’ with others.(20) The facilitation of nourishing and positive social relationships at school is as important as academic attainment, particularly for those children in the care system. To find out more please see the Learning, Skills and NEET section of the Kirklees Joint Strategic Assessment.

| A special note on: Vulnerable children with special educational need and/ or disabilities (SEND)

As with the general child population, typically a series of complex factors lead to disabled children and young people becoming looked after. This may involve family stress, the capacity of families to meet the care needs of their disabled child, neglect or abuse and in some instances parental illness and disability. The experience of being looked after also potentially increases the likelihood of developing emotional ill health issues. This is likely to be primarily assessed as a special educational need (SEN) and it should be noted that the number of children who solely present with emotional and behaviour challenges under the heading of disability may inflate the SEN looked after population. Children in Need (CIN) – There are currently around 1,900 Children in Need in Kirklees. Of these, one in three (32%) have an identified SEND. These range across all areas of need, however one in four of the CIN SEND group have social, emotional or mental health (SEMH) identified as their primary need. Children with Protection Plan – There are currently around 440 children and young people in Kirklees with a Child Protection Plan, of these one in seven (14%) have an identified SEND and one in 16 (6%) have a SEMHD. Looked after Children – Locally, we know there are around 700 looked after children of school age, of which one in four (24%) have an identified SEND. This means that of the overall SEND population 1,200 (16%) are in some part of the care system. As young people with SEND leave care and move into their young adult lives, we need to learn more about their experiences during the transition from child to adult services or the potential multiple disadvantage they may experience on the grounds of both disability and care leaver status.(21) |

For further details see the children living with special educational needs and or disabilities (SEND) section of the Kirklees Joint Strategic Assessment.

Work

When a person lacks income because of lack of work it influences their whole life, from their ability to obtain affordable goods and financial services through to obtaining and maintaining suitable housing. When the income level of a family is fixed, e.g. for people not in work, this means that as costs of food and energy rise, household budgets become overstretched and debts can escalate.

Income and Poverty

There has been a shift in the nature of poverty in Britain in the last decade. Whilst poverty remains a problem locally it has remained fairly stable with small reductions in pensioner poverty over the last few years. There is an underlying issue for a larger section of the population where overall living costs have increased and sudden changes to income and circumstances are having greater impacts on individuals and families, affecting relationships between people in households. To find out more see the Poverty section of the Kirklees Joint Strategic Assessment.

Risky behaviours

Criminality and Criminal Justice system (Child & Parent)

Most children with experience of care do not get into trouble with the law. However, children and young people who are, or have been, looked after are more likely than other children to get involved in the criminal justice system. Around half of the adults currently in custody in England and Wales have been in care at some point. (22) This tells us that there are opportunities being missed to turn young lives around and prevent future crime.

Children in care are significantly over-represented in the youth criminal justice system and in custody, where many have a particularly poor experience. Children in care who are at risk of offending need consistent emotional and practical support from their carers and other professionals and are likely to be especially vulnerable when they leave care. Care leavers are often expected to reach independence at a younger age and with less information and practical and emotional support, increasing their risk of criminalisation. 94% of children in care in England do not get in trouble with the law. However, children in care in England are six times more likely to be cautioned or convicted of an offence than other children.

| A special note on: Radicalisation

The current threat from terrorism and extremism in the UK is real and severe and can involve the exploitation of vulnerable people including children and young people. Children and young people can be drawn into violence or they can be exposed to the messages of extremist groups by many means. These can include exposure through the influence of family members or friends and/or direct contact with extremist groups and organisations or, increasingly, through the internet. Children and young people are vulnerable to contact or involvement with those who advocate violence as a means to a political or ideological end. It is important to note, that children and young people experiencing these situations or displaying these behaviours are not necessarily showing signs of being radicalised. The path towards radicalisation is similar to other vulnerabilities such as CSE where self-esteem and a poor home life can increase risks. There are a range of vulnerabilities associated with radicalisation: Personal Crisis – Family tensions; sense of isolation; adolescence; low self-esteem; disassociating from existing friendship group and becoming involved with a new and different group of friends; searching for answers to questions about identity, faith and belonging. Identity Crisis – Distance from cultural/religious heritage and uncomfortable with their place in the society around them. Personal Circumstances – Migration; local community tensions; events affecting country or region of origin; alienation from UK values; having a sense of grievance that is triggered by personal experience of racism or discrimination or aspects of Government policy. Unmet Aspirations – Perceptions of injustice; feeling of failure; rejection of civic life. Criminality – Experiences of imprisonment, poor resettlement/reintegration, and previous involvement with criminal groups.(23) |

Who are the vulnerable children living in Kirklees?

1. Children and families receiving Early Help

These are children and young people who are at risk of harm (but who have not yet reached the ‘significant harm’ threshold) and for whom a preventative service would provide the help that they and their family need to reduce the likelihood of that risk of harm escalating and the need for statutory intervention.

Locally there are around 2,538 potential children in receipt of early help in around 1,200 families. These include children whose family lives are affected by parental drug and alcohol dependency, domestic abuse and poor mental health. It is crucial that these children and their families benefit from the best quality professional help at the earliest opportunity. For some families, without early help, difficulties escalate, family circumstances deteriorate and children are more at risk of suffering significant harm.

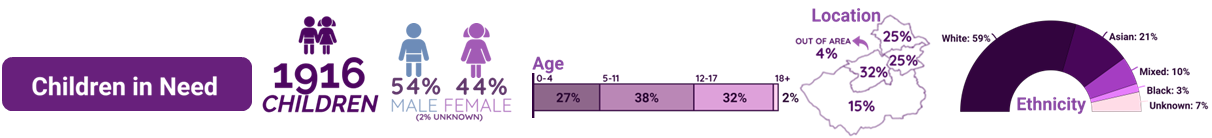

2. Children in Need

These are children and young people (or their families) who are receiving social work services where there are significant levels of concern about children’s safety and welfare, but these have not reached the significant harm threshold or the threshold to become looked after. They might also be children and young people who are missing from education or being offered alternative provision.

The term ‘child in need’ is a statutory term as set out in the Children Act 1989. Any child can be a child in need, even if they are living with their family. Being a child in need is not the same as being a looked after child (where a child is in local authority care further to a care order, or provided with accommodation by the local authority under section 20 of the 1989 Act).(24)

Understanding the Children in Need population in Kirklees (25):

- Numbers of children in need have been stable over the past five years, with small decreases in numbers over the past two years.

- Two in three (64%) children in need have a primary need caused by abuse or neglect. This has been the case for the last five years.

- One in eight (13%) children in need have a primary need caused by a disability. This proportion has remained fairly stable over the last five years.

- One in nine (11%) children in need have a primary need caused by family dysfunction. This proportion has remained fairly stable over the last five years.

- One in five (19%) cases had instances of domestic abuse.

- One in eight (12%) cases had instances or either parental or child mental health problems.

- One in 11 (9%) cases had instances of alcohol misuse in the household.

- One in 12 (8%) cases had instances of emotional abuse or neglect.

- One in 12 (7%) cases had issues around a learning disability.

- One in 14 (5%) cases had instances of physical abuse.

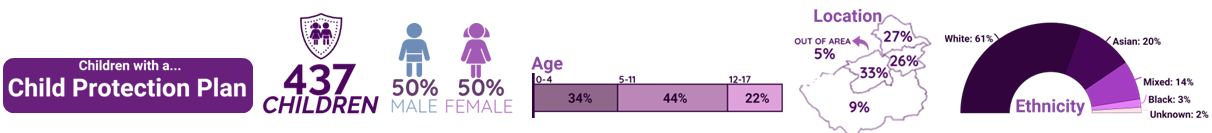

3. Children with Child Protection Plans (CPP)

These are children who become the subject of a multi-agency child protection plan (CPP) setting out the help that will be provided for them and their families to keep them safe and to promote their welfare.

Children and young people who are subject to a CPP are amongst the most vulnerable and disadvantaged members of society. A high proportion have been abused and neglected, with potentially long-term consequences for their future wellbeing. They may also have missed out on their education and failed to access adequate health care. Many of them will have experienced frequent changes of household, carer and school while living with their families.(26)

Understanding the local population of children with a child protection plan (CPP) (25):

- In 2016, one in two young people (44%) were subject to a CPP because of neglect. This has increased from one in three (32%) in 2012.

- Just fewer than one in three young people (35%) were subject to a CPP because of emotional abuse. This has decreased from almost one in two (49%) in 2013.

- One in six (16%) were subject to a CPP because of sexual abuse.

- One in 20 (5%) were subject to a CPP because of physical abuse.

A CPP tends to be a time-limited intervention. Typically a family will receive additional support or care interventions to allow them to get back on track. Alternatively a child may require to become looked after to further safeguard any vulnerability.

Locally around one in three (36%) child protection plans last 3 months or less, one in five (20%) lasting less than 6 months, and in most cases the remainder lasted less than a year.

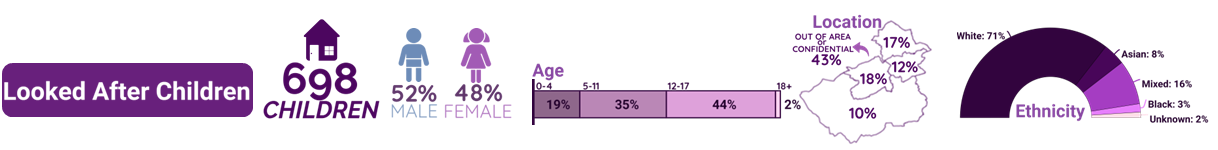

4. Looked After Children

These are children and young people being accommodated under section 20 or those ‘in care’ during or as a result of proceedings under section 31 of the Children Act 1989 and those accommodated through the police powers of protection and emergency protection orders.

A child is looked after by a local authority when a care order, granted by a court, gives the local authority corporate parental responsibility for the child. Alternatively, the council may provide accommodation for the child under a voluntary arrangement with the child’s parents, or if a child is remanded or convicted by the courts. Nearly two-thirds (62%) of children were in care because they had suffered abuse or neglect.

The looked after children population has remained around 640-650 over the past five years with a slight decrease in 2014. The latest data shows a slight increase in 2016.

Where looked after children in Kirklees live (27):

- Two in three (68%) looked after children live with foster carers.

- One in six (15%) looked after children live in children’s homes or semi-independent supported accommodation.

- One in 10 (10%) live with family members.

- Around 1 in 12 (7%) looked after children are adopted each year.

- Around one in four looked after children are placed outside Kirklees; sometimes for safety reasons and in other cases because the most suitable placement is not available within Kirklees.

When a child becomes looked after by the local authority, health checks, dental checks and emotional wellbeing assessments take place. In Kirklees there are only a very small number that do not receive these checks, primarily due to ongoing complex needs that need to be addressed prior to more mainstream health checks taking place.

| A special note on: Looked after children’s education and attainment

By their very nature looked after children are likely to have had a difficult start in life, this extends to their education both in terms of attainment and attendance. Looked after children may trail behind their peers in terms of academic attainment. There are also higher levels of SEND in the vulnerable children group (as described above). Locally: Key stage 1: on average half (49%) of looked after children reached their expected standard. Key stage 2: on average one in four (24%) of looked after children reached their expected standard. Key stage 4: on average one in five (22%) of looked after children achieved grade A-C in both Maths and English. The persistent absenteeism rate in local looked after children was 9%. (27) Absenteeism also impacts on educational attainment but it is important to remember that looked after children may come from chaotic and dysfunctional homes, where school attendance is not supported. |

What issues affect looked after children?

Children in care and care leavers are more likely to experience poor health, educational and social outcomes. Young people leaving care in the UK are five times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers.(28)

Few children or young people choose to become looked after. A high percentage enter the care system as a result of abuse or neglect, their experiences are also likely to have included one or more of the following: domestic violence, substance misusing parent(s), poverty, homelessness, the loss of a parent, or inadequate parenting. Whilst many remain in the care system only for brief periods, a considerable number spend a significant proportion of their childhood in care.

Children and young people who are looked after have the same core health needs as other young people, but what happens during childhood influences adult well-being and the likelihood of risk taking behaviours, employment, the development of ill health and disease. Looked after children have often experienced four or more Adverse Childhood Experiences placing them at much greater risk of poor adult outcomes.(14)

Emotional Wellbeing of Looked After Children

Mental health and wellbeing is a fundamental part of children’s general wellbeing, and is closely linked with physical health, life experience and life chances. Over half of mental health problems in adult life begin by age 14, and three quarters by age 18.(29) Mental health problems in children include emotional, conduct, depressive, hyper-kinetic, developmental, eating, habit and psychotic disorders and post-traumatic syndrome.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a measure of mental health in children aged 4-17 years. The SDQ uses 20 items relating to emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and peer problems to calculate a ‘total difficulty’ symptom score ranging from 0-40.(30) It is used nationally to benchmark the mental wellbeing of looked after children. A higher score on the SDQ indicates more emotional difficulties. A score of 0 to 13 is considered normal, a score of 14 to 16 is considered borderline cause for concern and a score of 17 and over is a cause for concern. The average score in Kirklees for looked after children was a score of 13.2. (31)

Research on resilience has consistently demonstrated that having a trusting relationship with one key adult is strongly associated with healthy development and recovery after experiencing adversity. The availability of a key adult has been shown to be the turning point in many looked after young people’s lives. Creating and sustaining community interactions, networks and friendships represent major challenges for looked after children and especially those who have particular needs.(32)

Health and Wellbeing of looked after children

It is estimated that a quarter of young women leaving care are pregnant or have a child within 18-24 months of leaving care. Teenagers who become parents are known to experience greater educational, health, social and economic difficulties than young people who are not parents, and their children may be exposed to the consequences of greater social deprivation and disadvantage.(33)

4% of looked after children are identified as having a substance misuse problem and 11% of looked after children aged 16-17 years are identified as having a substance misuse problem.(34)

Children’s early experiences can have long-term impacts on their emotional and physical health, social development, education and future employment. Children in care do less well in school than their peers.(35)

The impact of being looked after

Evidence shows that having multiple care placements reduces children’s opportunities to develop secure attachments. It may also worsen any existing behavioural and emotional difficulties. An out-of-authority placement is a care setting for a looked-after child outside the boundaries of the authority that is legally responsible for that child. In some cases, there may be good reasons for placing a child at a distance, for example to break links with undesirable peer groups, but evidence suggests that vulnerable children placed outside their authority, especially those placed a long distance away may be at risk.(36)

Achieving accommodation permanence requires children to experience not only physical permanence in the form of a family and a home but also a sense of emotional permanence; of belonging and the opportunity to build a strong identity. In many circumstances children will need support to make sense of being part of two families or to manage complex and sometimes difficult relationships.

National figures show that of the children who returned home from care in England in 2006/7, 30% had re-entered care during the five years to March 2012. This was attributed to poor assessments about whether the child should be returning home, inadequate preparation for returning home, and lack of monitoring post-return. If problems are not addressed, particularly those relating to children’s behavioural and emotional difficulties or parental drug and alcohol misuse, the stability of returning home is compromised.

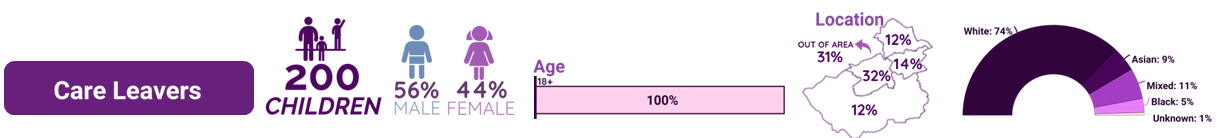

5. Care Leavers

Care leavers are children aged 16-17 years who are preparing to leave care and qualify as ‘eligible’; those aged 16-17 years who have left care and qualify as ‘relevant’; those aged 18 and above and qualify as ‘former relevant;’ and those aged 18-25 years who qualify as ‘former relevant children pursuing further education or training’. These include those living in homes of multiple occupation, those who have left care to return home or are living with families under a special guardianship order, child arrangements order or adoption order.

Under the Leaving Care Act, the Local Authority has a duty towards eligible, relevant and former relevant children. For children aged 16-18 years, this includes offering financial support, providing a Personal Adviser and to ensure they have accommodation. For those aged 18-21 years, contact should be maintained and support provided by a Personal Adviser along with assisting with costs for education, employment and training.

What do care leavers do once they leave care?

- One in two (45%) care leavers are in some form of education or employment;

- one in four are in employment

- one in eight are in education excluding higher education

- one in 16 are in higher education

- This means half are not in education or employed. Where the reasons are known for this, the most common are disability, pregnancy or being a parent. (27)

What issues affect young people leaving care?

For the majority of young people today their journey to adulthood often extends into their mid-twenties. In contrast, the journey to adulthood for many young care leavers is shorter, steeper and often more hazardous. Those leaving care may struggle to cope with the transition to adulthood and may experience social exclusion, unemployment, early pregnancy, health problems, custody or homelessness.

From 2008, the government has required local authorities to support care leavers up to the age of 25 years if they remained in, or planned to return to, education and training. Subsequently, the Children and Families Act 2014 introduced ‘staying put’ arrangements which allow children in care to stay with their foster families until the age of 21 years, providing both parties are happy to do so.

Young people leaving care may be ill-equipped with the life-skills which enable them to make connections and build networks. The role of networks and community relationships may enhance the potential effects of new and positive opportunities.(32)

Young people leaving care report poorer health and well-being than that of young people who have never been in care. Many aspects of young people’s health have been shown to worsen in the year after leaving care. Compared to within three months of leaving care, young people interviewed a year later were almost twice as likely to have problems with drugs or alcohol (increased from 18% to 32%) and to report mental health problems (12% to 24%). There was also increased reporting of ‘other health problems’ (28% to 44%), including asthma, weight loss, allergies, flu and illnesses related to drug or alcohol misuse and pregnancy. Unlike most of their peers, care leavers have to deal with such problems while learning to live independently.(37)

Many looked after children have experienced neglect, harm and distress so they are particularly vulnerable to poor mental health and poor emotional health and well-being. Mental wellbeing affects the capacity to learn, to communicate and to form and sustain relationships and influences the ability to cope with change, transition and life events.(38)

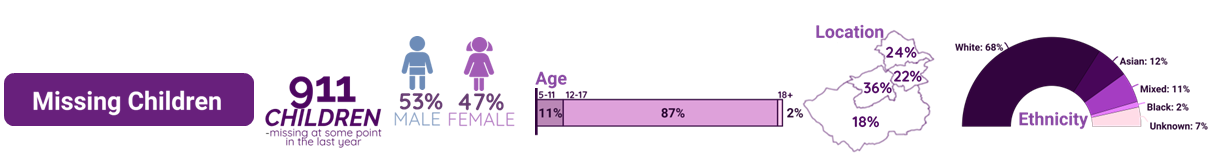

6. Missing Children

Children may run away from a problem, such as abuse or neglect at home, or to somewhere they want to be. They may have been coerced to run away by someone else. Whatever the reason, it is thought that approximately 25% of children and young people that go missing are at risk of serious harm.(39) There are particular concerns about the links between children running away and the risks of sexual exploitation. Missing children may also be vulnerable to other forms of exploitation, to violent crime, gang exploitation, or to drug and alcohol misuse.

Whilst the number of looked after children going missing is a small percentage of all children that go missing it is disproportionately high compared with the children’s population as a whole, especially in the cohort of children who repeatedly go missing.(40) Whilst the majority of children who go missing are not looked after, and go missing from their family home, it is the case that looked after children are particularly vulnerable when they go missing. Looked after children who go missing, do so more often and are at greater risk of harm including CSE.

What do we know about children who go missing?

Nationally:

- In 2016, there were 41,285 children missing incidents relating to 10,395 individual children. 89% of these incidents involved looked after children.(41)

- There is a group of children who repeatedly go missing. Nationally around 59% of the missing children incidents are attributable to repeat missing episodes. Repeatedly going missing should not be viewed as a normal pattern of behaviour, for example, repeat episodes of a child going missing can indicate sexual exploitation.

Locally:

- Three in four (75%) children who went missing in Kirklees in 2016 were not looked after by the local authority although they may have been subject to a protection plan or a child in need.

- One in ten (11%) children who went missing in Kirklees in 2016 were looked after by the local authority.

- Locally one in seven (14%) looked after children have been reported missing and there is a smaller cohort of looked after children who repeatedly go missing.

- 27% of cases go missing on multiple occasions – some as many as 40 times in a year

- The highest incidence of missing was seen in the 13-17 year age group. The most common single year age group to go missing was 15 year olds.

- Boys go missing more frequently than girls up to around 14 years of age then the trend reverses.

- It is known that local ‘hot spots’ exist for missing children: these include transport hubs and fast food restaurants – often as meeting places and also where there is free wi-fi.

What are the causes of children going missing?

- Around two in three children who go missing take up the opportunity to have a ‘return interview’. This is partly to understand why they went missing, if they were at risk when they were missing and how they can be supported better in the future.

- Amongst the total missing children cohort, the most common reasons for going missing are (1) to be with family / friends (2) problems at home e.g. lifestyle / boundary issues (3) school and education issues.

- One in five (22%) missing children reported issues with school or education as a reason for going missing, compared with one in 14 missing looked after children.

- Half (53%) of missing children reported lifestyle and/or personal problems as a reason for going missing, compared with two in three (66%) missing looked after children.

- Three in five (61%) missing children cited problems at home as a reason compared with one in three (33%) missing looked after children.

What are the assets around the issue?

Assets are hugely important to how we feel about ourselves, the strength of our social and community connections and how these shape our health and wellbeing. Promoting resilience in children, young people and families is not just about putting a service in place to ‘fix’ a problem, it is about building on people’s strengths and giving them the tools they need to keep them away from the ‘red’ end of the continuum of care.

Health assets are those things that enhance the ability of individuals, communities and populations to maintain and sustain health and well-being. These include things like skills, capacity, knowledge, networks and connections, the effectiveness of groups and organisations and local physical and economic resources.

Children’s Rights Team

The local Children’s Rights Team (CRT) offer an Advocacy Service for children and young people in care and leaving care, ensuring their wishes and feelings are heard. An advocate is available to support a child or young person at the time of their Review and also if a child or young person wants to raise a complaint.

Every looked after child has a right to an Independent Visitor and in Kirklees, this scheme is co-ordinated by CRT. This work includes the recruiting, training and supporting of volunteers, appropriate matching to young people, supervision of volunteers and monitoring of the scheme.

CRT facilitates the delivery of Total Respect training. Total Respect is a national training resource delivered by young people who have experience of care. The course is for adults responsible for or working with children or young people in care. The two-day course is designed to energise, motivate and encourage adults to think about how children and young people experience being looked after.

CRT also support young people who are or have been looked after to contribute to The Skills to Foster training course providing potential foster carers with a unique insight into their experience of care.

Young people have shared their experiences and expertise as part of the peer mentoring group and have emphasised the need for support and assistance around life skills. As a result an accredited “living independently” course has been developed that will cover key themes of time keeping, household tasks, budgeting and cooking.

Involving Young Citizens Equally (IYCE)

In order to offer opportunities for engagement to children and young people from all backgrounds and abilities, IYCE have established a flexible model of stakeholder engagement, the key elements are Kirklees Youth Council; Our Voice (Kirklees young advisors); ad hoc voice & influence activity; social media and training for adults. Examples of participation activity and its impact include work on the town centres, libraries, and aspects of commissioning such as young carers and emotional health and wellbeing. The IYCE Team work closely with others who are engaged in youth voice activity to ensure a stronger “voice” and an ability to provide decision makers with feedback from a wide range of children and young people.

The Kirklees Fostering Network (KFN)

The Kirklees Fostering Network (KFN) is an organisation run by local foster carers for the benefit of all foster carers in Kirklees. The network offers extra support to run alongside the support that foster carers received from Social Care. It aims to provide a collective voice for foster carers. The network also offers support and information to families that are thinking about becoming Kirklees foster carers or who are currently going through the assessment process.

Schools as community hubs

Schools engage with families and children every day and they have a valuable position within our communities. It is therefore critical that the council, schools and their partners work more closely together as we begin to shape future services.

In Kirklees there are a number of schools developing partnership arrangements and each partnership is committed to working to a collective vision of: Strong partnerships of schools (hubs) as the vehicle for delivering a range of services for children, families and the wider community.

Emerging outcomes for the partnerships include improving health and social care outcomes for children and families, making the most of local insight and intelligence to respond to local need and statutory responsibilities, making the most of resources and assets (including their school), supporting locally delivered services and community based solutions where relationships with children and families are key, wrap around family care and universal, prevention interventions.

Looked After Children who go missing

A three to six month pilot scheme (from June 2017) provides a bespoke service for Kirklees Looked After Children who are placed in Kirklees and within a 20 mile radius from their home address who have gone missing. The service includes the offer of ‘return interviews’ with senior key workers rather than the ‘duty worker’ from the Early Intervention and Targeted Support service (EITS). The aim of the pilot scheme is to increase the take-up and quality of return interviews, reduce the number of missing episodes (including repeat episodes) and improve the outcomes for looked after children.

Views of local people

There is a range of local intelligence gathered from those who are in or have been in the care of the local authority:

Kirklees Children in Care Council

The Children in Care Council (CiCC) and the Care Leavers’ Forum (CLF) are the voice for children and young people in the care of Kirklees Council. The CiCC is made up of children and young people aged 11-16 years placed with foster carers and those living in residential homes. The CLF is for young people aged 16-21 years who may be in supported lodgings or living independently.

Key Messages from the Children in Care Council and Care Leavers Forum ensure that children and young people in care and care leavers are:

- Provided with stability

- Supported by staff who are passionate and enthusiastic about their care

- Listened to

- Helped to stay in touch with family and friends

- Helped to stay healthy and make healthy choices

- Supported through education and beyond

- Provided with sport and leisure opportunities

- Respecting and honouring your identity

- Given the information they need from being in care to adulthood and beyond.

The CiCC and CLF identified two challenges as being especially important to them:

- Communication and using modern technology to keep in touch.

- Support after leaving care.

From a survey of Care Leavers “The experiences of looked after children with foster carers in Kirklees” in 2015 the following key themes were identified:

- Excitement at having independence and freedom.

- The loneliness and loss of relationships.

- Preparation for independence.

- Care leavers felt their social workers/ PA had listened to them.

Experience of placement

In 2016 a survey of children and young people, looked after by Kirklees Council and placed with foster carers or in residential homes outside of Kirklees provided the following feedback:

- Most were happy where they are living

- All said they have someone they can talk to about how they feel

- 50% of those responding say they were involved in deciding where they would live

- One young person said they didn’t understand the reasons why they are living where they are

- Most said they see or speak to their Social Worker enough

- Just over 50% said they don’t speak to their Independent Reviewing Officer between reviews

- Slightly more than 50% said they don’t have enough contact with family and friends

National Children in Care and Care Leavers Survey

The Children’s Commissioner publishes regular State of the Nation reports into aspects of children’s lives. The first of five annual reports, published in August 2015, focuses on the experience of children in care and care leavers.

The Children’s Commissioner argues that:

- It is essential that children’s views are sought and influence all decisions that are made about them and that all decisions are fully explained to them.

- Support for all care leavers is extended up to 25 years of age.

- Every child in care should have at least one continuing and consistent relationship with someone who is there for them through their time in care and into adulthood.

- Services should enable children to keep their social worker for longer through their time in care.

- Every child in care should have access to high quality therapeutic care that will enable them to recover from past harm and build resilience and emotional wellbeing.

National research (42) reinforces some of the local work with those in the care system, who said:

- We want to know what we can expect from a service (clear information, use a variety of ways to get the information through, quality standards) Young people say that information about who to contact when in crisis or need support should be readily available, preferably online.

- Give us choice and let us use our own coping and resilience skills but offer us help when we are struggling.

- Have the right adults working with us – people we can trust, who we can talk to in confidence, who are not judgemental, who like young people.

- Provide young people friendly venues – with a range of services in one building, friendly and welcoming, relaxed and informal culture, clean and safe, choice of venue within walking distance of home or something more centrally accessible.

- Offer us flexible and accessible services – not 9am-5pm or wait until Monday, access to all inclusive services that can support all aspects of our lives, drop in services and self-referral, opportunity to take part in activities that are creative and fun and help build a range of softer skills such as friendships.

- We want to know what we can expect from a service and are able to make choices – choice about the kind of support we receive, so we are part of the solution and things are not just “done to us”

Children and young people have been consistently clear that they see combined support for their parents, carers, siblings and friends as being very important. They suggest “skilling up” the family to help each other; enabling families to reflect on their behaviour, communicate effectively and learn how they impact on each other. Children and young people want to be able to discuss problems, knowing parents and carers have the knowledge and resources to help support them.

A key theme which has emerged from young people is that if a person can manage a difficult experience without adult intervention, it is better for them. Helping children and young people to develop coping strategies in advance of any difficult situations was a clear suggestion from young people. Young people being provided with the knowledge of what support is on offer and where to seek it is vital.(42)

What should commissioners and service planners consider?

Data and Intelligence:

- Model the future profile of the vulnerable child population based on trends in birth rates and migration.

- Better understand the relationship between poverty, neglect and family dysfunction.

- Develop a better understanding of the reasons children and parents need early help; the relationship between different risk factors.

- Improve business intelligence to understand how many children move between ‘early help’, ‘children in need’, ‘child protection plan’ and ‘looked after’ status and the reasons for these transitions. For example, use longitudinal case reviews to provide insights into vulnerable children’s journeys through the care system and identify opportunities for prevention and earlier intervention.

- Embed a holistic approach to understanding the needs of vulnerable children with SEND and their families.

- Develop a better understanding of the health of looked after children including health outcomes; and the causes and prevention of placement instability and breakdown.

- Develop a better understanding of the profile of missing children and the needs of their parents/ carers and the factors underpinning repeated missing episodes.

- Review the approach to assessing educational ability, attainment and aspirations of vulnerable children.

- Develop a clear up to date strategy for commissioning and developing services including information on what is on offer to vulnerable children and the timescales for which they will gain support.

- Identify any links between vulnerable children needs and to corporate parenting objectives such as for education and housing

Commissioning:

- Use an evidence-informed approach – research consistently shows that early intervention and promoting resilience in children and families can help them manage their vulnerabilities and avoid the need for high-end intervention.

- Commission support that builds on existing strengths and assets that support vulnerable children and which responds to unmet needs in particular places or amongst particular communities.

- Build on the work of the Stronger Families programme to understand and address the cross-generational impact and trends of vulnerability. For example, the sustained improved outcomes from the Family Intervention Project; and evidence of the cost savings in reduced crime and anti-social behaviour by getting adults into work.

- Build a strengths based approach to developing good home environments across support provision.

- Build on current assets that support looked after children to prepare for independence and adulthood. Ensure this encourages long term mentoring to enable looked after children and care leavers to access support beyond statutory responsibilities of the local authority, e.g. life skills, employability, building positive networks and relationships, housing, finance and money management.

- Ensure that the views and experiences of children and young people living in Kirklees are the centre of service design.

- Work with partner organisations and commissioned services to improve and encourage best practice ensuring there is a clear line of accountability.

- Continue to develop CAMHS support for vulnerable children and their carers.

- Continue to invest in sexual health support targeted at vulnerable children; invest in sexual health and relationship support for those in the vulnerable cohort.

Collaboration and Development:

- Continue to learn with and from all partners and build the evidence of what works locally.

- Improve awareness of risk amongst all children and help them to learn different coping strategies.

- Upskill and provide guidance for professionals to understand the emotional impacts of neglect and support those who have experienced neglect. For example, in schools where poor attendance or behaviour may be caused by an emotional response to neglect.

- Support developing school hub programmes that build and improve protective factors in vulnerable children. Also explore options for embedding knowledge about protective factors and how to develop them in parenting support programmes.

- Work with colleagues in criminal justice to offer better support to current and former looked after children in the justice system and to understand the underlying causes.

References

- West Yorkshire Central Services. GP registered population in Kirklees, 2002 and 2015.

- Department for Education. Schools, pupils and their characteristics: January 2016 – GOV.UK . Statistics: school and pupil numbers.

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC). In harm’s way : The role of the police in keeping children safe. 2015

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Child Sexual Exploitation : Improving Recognition and Response in Health Settings. 2014

- NICE. Child Abuse and Neglect, NICE guideline: Short Version, Draft for Consultation. 2017

- Lazenbatt A. The impact of abuse and neglect on the health and mental health of children and young people. 2010

- Department for Education. The impacts of abuse and neglect on children; and comparison of different placement options. 2017

- Guy J, Feinstein L, Griffiths A. Early intervention in domestic violence and abuse. 2014

- Social Services Improvement Agency. What works in promoting good outcomes for children in need who experience domestic violence? 2007

- British Medical Association. Alcohol and pregnancy Preventing and managing fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. 2016

- Department for Children Schools and Families & Department of Health. Child Protection, Domestic Violence and Parental Substance Misuse: Family Experiences and Effective Practice. 2008

- The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, Prevention Working Group Enquiry. Hidden Harm- responding to the needs of children of problem drug users. 2002

- Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Perkins C, Lowey H. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):72

- Selwyn J, Briheim-Crookall L. Our Lives, Our Care: Looked after children’s views on their well-being. 2017

- Shaw J, Turnbull P. Suicide by children and young people in England: National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (NCISH). 2016

- Social Care Institute for Excellence. Preventing Teenage Pregnancy in Looked After Children. 2004

- Wilson W, Fears C. Overcrowded housing (England). 2014.

- Kirklees Council. Kirklees Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2015. 2015.

- Department for Children Schools and Families & Department of Health. Promoting the educational achievement of looked after children: Statutory guidance for local authorities. 2010

- Ridge T. The Everyday Costs of Poverty in Childhood: A Review of Qualitative Research Exploring the Lives and Experiences of Low-Income Children in the UK. Child Soc. 2010;25(1):73–84.

- Kelly B, Dowling S, Winter K. Disabled Children and Young People who are Looked After: A Literature Review.2012

- Prison Reform Trust. In Care, Out of Trouble. 2016

- HM Government. Revised Prevent Duty Guidance: for England and Wales. 2015

- Jarrett T. Briefing Paper: Local authority support for children in need (England). 2016

- Department for Education. Statistics: children in need and child protection – GOV.UK Data collection and statistical returns, Looked-after children, and Safeguarding children. 2016

- Sempik J, Ward H, Darker I. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties of Children and Young People at Entry into Care. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;13(2):221–33.

- Department for Education. Statistics: looked-after children – GOV.UK Data collection and statistical returns and Looked-after children. 2017

- House of Commons Education Committee. Mental health and well-being of looked-after children. 2016

- Mooney A, Statham J, Monck E, Chambers H. Promoting the Health of Looked After Children: A study to inform revision of the 2002 Guidance. 2009

- Meltzer H, Gatward R, Corbin T, Goodman R, Ford T. The mental health of young people looked after by local authorities in England. 2003;

- Department for Education. Children looked after in England (including adoption and care leavers), year ending 31 March 2016: additional tables. 2016

- Hicks L, Simpson D, Mathews I, Koorts H, Hicks L, Simpson D, et al. Communities in care : A scoping review to establish the relationship of community to the lives of looked after children and young people. 2012.

- Social Services Improvement Agency. What Works in Promoting Good Outcomes for Looked After Children and Young People? 2008

- Local Government Association. Healthy futures: supporting and promoting the health needs of looked after children. 2016

- Department for Education. Promoting the education of Looked after children: Statutory guidance for local authorities. 2014

- The National Audit Office. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General: Children in care. 2014

- Department for Children Schools and Families & Department of Health. Statutory Guidance on Promoting the Health and Well-being of Looked After Children. 2009

- Goddard J, Barrett S. The Health Needs of Young People Leaving Care in Bradford District. Bradford: University of East Anglia; 2007.

- Bywaters P, Bunting L, Davidson G, Hanratty J, Mason W, Mccartan C, et al. The relationship between poverty, child abuse and neglect: an evidence review. 2016.

- Department for Education. Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care. 2014

- National Crime Agency. Missing Persons Data Report 2014/2015. 2016.

- Bundle A. Health information and teenagers in residential care: a qualitative study to identify young people’s views. Adopt Foster. 2002;26(4):19–25.

Additional resources

- CAMHS strategy

- CDOP report

- Children’s Commissioner Report July 2017: On measuring the number of vulnerable children in England

- Family Information Directory

- Learning Skills Annual Report 2016

- Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Safeguarding Factsheet 7. (2017) A collaborative piece of work produced by Kirklees Safeguarding Adults Board (KSAB), Kirklees Safeguarding Children Board (KSCB) and Community Safety Partnerships (CSP)

If you are concerned that an child living in Kirklees is at risk of being abused you should see Concerns about a child

Date this section was last reviewed

07/07/17